Authors of research papers and articles on global issues for this month

AMMAR BANNI, Candice Bernd, David Bollier, Iolanda Brazão,

Alphonse HITIMANA CAMEROUN, Noam Chomsky, Countercurrents.org, Guy Crequie (2),

Marianne de Nazareth, Thom Hartmann, George Lakoff, Abby Martin, Rajesh Makwana,

Rolly Montpellier, Rachel Morello-Frosch, Joseph Nevins,

Manuel Pastor, Mary Pipher, Isabel Cristina Silva Vargas

AMMAR BANNI, To live in peace in all day of year ![]()

Candice Bernd, Arrests Mount in Texas Blockade Over Tar Sands Pipeline ![]()

David Bollier, The Commons As A Transformative Vision ![]()

Iolanda Brazão, Paz & amor ![]()

Alphonse HITIMANA CAMEROUN, LETTRE A MON FRERE ![]()

Noam Chomsky, My Visit to Gaza, the World's Largest Open-Air Prison ![]()

Countercurrents.org, Global CO2 Emission Rises To Record Level In 2011 ![]()

Guy Crequie Une longue série de poèmes de paix d'enfants et d'adolescents ![]()

Guy Crequie LA PAIX = CITADELLE DU MONDE ! ![]()

Marianne de Nazareth, Approximately 50 % Of World’s Wetlands Lost During The 20th Century ![]()

Thom Hartmann, Globalization Is The Number One Health Risk Facing Humanity ![]()

George Lakoff, Global Warming Systemically Caused Hurricane Sandy ![]()

Abby Martin, Iran/USA: Who is Threatening Who? ![]()

Rajesh Makwana, Proposing A Vision Of A New Earth ![]()

Rolly Montpellier, Climate Change: Food Crisis And Future Hunger Wars ![]()

Rachel Morello-Frosch, Manuel Pastor Facing the Climate Gap: How Low-Income Communities of Color Are Leading the Charge on Climate Solutions , ![]()

Joseph Nevins, Can We Survive the Lifestyle Choices of the Planet’s Ecologically Privileged Class? ![]()

Rachel Morello-Frosch, Manuel Pastor Facing the Climate Gap: How Low-Income Communities of Color Are Leading the Charge on Climate Solutions , ![]()

Mary Pipher, Wake Up! Our World Is Dying and We're All in Denial ![]()

Isabel Cristina Silva Vargas, A PAZ COMO REALIDADE ![]()

| Day data received | Theme or issue | Read article or paper |

|---|---|---|

| November 14, 2012 | by Countercurrents.org, Countercurrents.org Global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels rose 2.5 percent to a record in 2011 on surging pollution in China , Germany 's research institute IWR said. At the same time, scientists have found human produced CO2 emissions are accumulating in greater amounts in the upper reaches of the atmosphere. Stefan Nicola reports [1]: Worldwide emissions rose 834 million metric tons to 33.99 billion tons, IWR said on November 12, 2012 . China 's releases of the GHG climbed 6.5 percent, offsetting declines in the US , Russia and Germany , the institute said. ?If the current trend persists, global CO2 emissions will go up by another 20 percent to over 40 billion tons by 2020,? Norbert Allnoch, the IWR's director, said in the statement. Countries' emission levels should be tied to mandatory investments in climate protection such as renewable energy, the IWR said. Economies including Brazil , China and India are raising investments in renewable technologies to help meet their growing energy demand. The projected surge in low-carbon sources won't be enough to meet the UN goal of limiting global warming since industrialization to 2 degrees Celsius, the International Energy Agency said on November 12, 2012 . China was the biggest polluter, with emissions of 8.9 billion tons. The US produced about 6 billion tons of carbon dioxide and India was the third-biggest emitter with 1.8 billion tons, the IWR data show. From Frankfurt Reuters reported: In terms of producing CO2 India was third, ahead of Russia , Japan and Germany . Global CO2 emissions are 50 percent above those in 1990, the basis year for the Kyoto Climate Protocol. The first period of the Kyoto Protocol ends on Dec. 31 and moves straight into a new commitment period. The length of the new period should be decided when world leaders meet in Doha this month at a UN summit on climate change. The summit aims to finalise a new binding emissions reduction agreement by 2015, which would come in to force in 2020. Along with this negative development, scientists have found human produced carbon dioxide emissions are accumulating in greater amounts in the upper reaches of the atmosphere, wrote Carl Franzen [2] on November 13, 2012 : Citing results of a new study of data captured by a Canadian satellite Carl referred to the key finding of a team at the University of Waterloo in Canada and the US Naval Research Laboratory's (NRL) Space Science Division, relayed in a new paper published Sunday online in the journal Nature Geoscience. The team analyzed eight-years worth of atmospheric CO2 data collected by the Canadian Space Agency's Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE), a satellite launched in 2003 that is taking spectra measurements and images of the atmosphere. The scientists finding from the ACE's data from 2004 through 2012 was troubling: Carbon dioxide levels in the upper atmosphere increased eight percent over the period, from 209 parts per million in 2004 to 225 parts per million in 2012. The NRL described in a news release on the findings: ?The scientists estimate that the concentration of carbon near 100 km altitude is increasing at a rate of 23.5 ± 6.3 parts per million (ppm) per decade, which is about 10 ppm/decade faster than predicted by upper atmospheric model simulations.? At lower altitudes, carbon dioxide emissions make the Earth warmer by trapping sunlight. But at higher altitudes, the reverse is true: In the mesosphere (between 31 miles and 55 miles up) and the thermosphere (above 55 miles up), carbon dioxide's density is thinner and a less effective at trapping infrared radiation. In fact, CO2 at these altitudes is something of a heat sink, allowing infrared radiation to escape back out into space. The thinning, cooling trend at this level due to increasing CO2 is likely to have detrimental effects on human spacefaring activity, something of a bitter irony given that a satellite was the reason we know about the increased CO2 levels in the first place. The NRL explained: ?The enhanced cooling produced by the increasing CO2 should result in a more contracted thermosphere, where many satellites, including the International Space Station, operate. The contraction of the thermosphere will reduce atmospheric drag on satellites and may have adverse consequences for the already unstable orbital debris environment, because it will slow the rate at which debris burn up in the atmosphere.? In other words, rather than trapping heat, the increased CO2 levels in the upper atmosphere are likely to result in longer-lasting debris, and thus, a greater proportion of debris over time as humans continue to launch objects into space. Already, NASA's Orbital Debris Program, which tracks the overall amount of space junk around the planet, reports that there are at least 500,000 objects orbiting the Earth between 1 and 10 centimeters in size, another 21,000 larger than 10 centimeters. Other scientists have previously warned that Earth is collectively approaching a ?tipping point? when it comes to space junk, where one piece of space junk colliding into another could set off a chain reaction of cascading collisions that would make it prohibitively risky to launch anything else into space, a phenomena known as the ?Kessler effect? or the ?Kessler syndrome? after the scientist who first proposed it in 1978. Space junk has become such a looming problem that the NRL has concocted a plan to reduce some of it by shooting clouds of dust into space to increase the drag on debris and bring them plummeting back to Earth, to burn up in the atmosphere. That idea remains just a proposal, for now. Source: [1] Bloomberg, ?Global Carbon Emissions Climbed to a Record Last Year, IWR Says?, Nov 13, 2012 , http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-11-13/global-carbon-emissions-climbed-to-a-record-last-year-iwr-says.html [2] TPM, ?Carbon Dioxide Emissions Reaching Upper Atmosphere, Canadian Space Satellite Finds?, http://idealab.talkingpointsmemo.com/2012/11/carbon-dioxide-emissions-reaching-upper-atmosphere-canadian-space-satellite-finds.php |

Read |

| November 9, 2012 | by Rolly Montpellier, Countercurrents.org In a recent post I wrote about Overpopulation: Food Crisis and future Hunger Wars. The article focused on the impact of the population explosion on food supplies – will there be enough food for a population of 9 billion in 2050? There are many interrelated and complex factors affecting worldwide food production. Climate change is singularly the most critical factor. The “Final” Wake-up Call There have been many so-called wake-up calls about the environmental slippery slope humanity finds itself on. The summer of 2012 – raging wildfires, drought, extreme heat, (more than 3000 high-temperature records broken) “affecting 87 per cent of the land dedicated to growing corn, 63 per cent of the land for hay and 72 per cent of the land used for cattle” and now hurricane Sandy. Americans collectively have reached the “wow” moment. Even prior to hurricane Sandy, 70% of Americans believed that climate change is not a hoax. See previous blog - Common Sense Revolution. The U.S. drought is having global effects as the world’s biggest grain exporter struggles with shortfalls. Drought conditions affected over more than 60 percent of the lower 48 states, the government said. The same is happening elsewhere around the globe. A Centre for Strategic & International Studies report by (Johanna Nesseth Tuttle & Anna Applefield) stresses that corn prices have risen 45 per cent since mid-June as a result of the drought. Global food prices are at an all-time high. Since the United States is the world’s top exporter of both of these crops, significant disruptions in domestic production can impact global food prices. In fact, 40 percent of the wheat and soya beans traded on the global market last year were grown in the United States. Climate change is now widely believed to be the cause of the intensification of weather patterns that disrupt food production around the globe. Human-induced climate change will intensify the geographic extent, duration and severity of storms – winds, flooding, drought, extreme heat and snowfalls. “Perhaps the biggest single question about climate change is whether people will have enough to eat in coming decades”, says Justin Gillis in the NYT Environment/Green Blog:

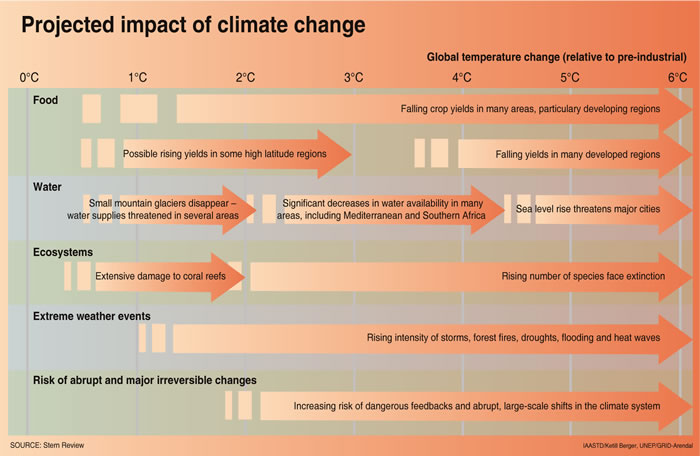

Extreme weather will intensify and aggravate future food crises. An article appearing in Arctic News recently highlights that:

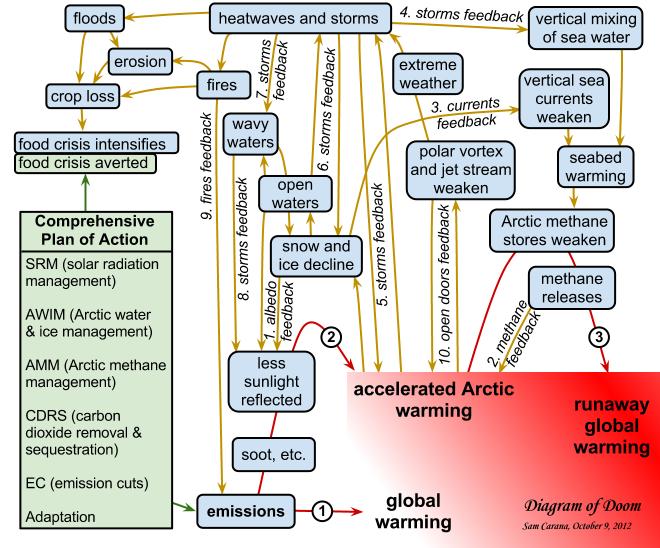

Arctic News also features the Diagram of Doom which pictures three kinds of warming and 10 catastrophic feedbacks.

Diagram of Doom Changing extreme events An IPCC Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation (November 2011) highlights the following findings: • Observations since 1950 show changes in some extreme events, particularly daily temperature extremes, and heat waves • It is likely that the frequency of heavy precipitation will increase in the 21st century over many regions • It is virtually certain that increases in the frequency of warm daily temperature extremes and decreases in cold extremes will occur…very likely—90 per cent to 100 per cent probability—that heat waves will increase in length, frequency, and/or intensity over most land areas. • It is likely that the average maximum wind speed of tropical cyclones (also known as typhoons or hurricanes) will increase throughout the coming century • There is evidence… that droughts will intensify over the coming century in southern Europe and the Mediterranean region, central Europe, central North America, Central America and Mexico, northeast Brazil, and southern Africa. • It is very likely that average sea level rise will contribute to upward trends in extreme sea levels in extreme coastal high water levels. Impacts of Climate Change on Yield The following excerpts are from a UNEP study about the impact of environmental changes on world food production – The environmental food crisis – The environment’s role in averting future food crises:

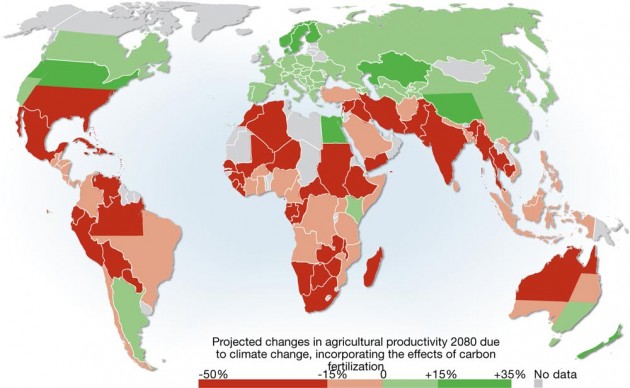

Projected losses in food production due to climate change by 20.80. (Source: Cline, 2007). Impacts of Water Scarcity Water is essential not only to human survival but in food production. The UNEP study reports that:

Projected losses in food production due to climate change by 2080 The wars of the future will be ‘Hunger Wars’ fought over the resources that are left. I’m a blogger, writer and activist. My burning desire to do something about the plight of our world has resulted in the creation of a Blog that allows me to express my beliefs about our times. It is my vehicle to dialogue, to share my opinions and to scream for more social justice, true democracy, political correctness, a more mindful society, taking responsibility and ensuring a better future for my children and grandchildren. I owe them that much. That will be my legacy. |

Read |

| October 31, 2012 | by David Bollier, On the Commons, Countercurrents.org

Beyond the Market and State For generations, the state and market have developed a close, symbiotic relationship, to the extent of forging what might be called the market/state duopoly. Both are deeply committed to a shared vision of technological progress and market competition, enframed in a liberal, nominally democratic polity that revolves around individual freedom and rights. Market and state collaborate intimately and together have constructed an integrated worldview – a political philosophy and cultural epistemology, in fact – with each playing complementary roles to enact their shared utopian ideals of endless growth and consumer satisfaction. The market uses the price system and its private management of people, capital and resources to generate material wealth. And the state represents the will of the people while facilitating the fair functioning of the “free market.” Or so goes the grand narrative. This ideal of “democratic capitalism” is said to maximize the well-being of consumers while enlarging individual political and economic freedoms. This, truly, is the essence of the modern creed of “progress.” Historically, the market/state partnership has been a fruitful one for both. Markets have prospered from the state’s provisioning of infrastructure and oversight of investment and market activity. Markets have also benefited from the state’s providing of free and discounted access to public forests, minerals, airwaves, research and other public resources. For its part, the state, as designed today, depends upon market growth as a vital source of tax revenue and jobs for people – and as a way to avoid dealing with inequalities of wealth and social opportunity, two politically explosive challenges. The financial meltdown of 2007-2008 revealed that the textbook idealization of democratic capitalism is largely a sham. The “free market” is not in fact self-regulating and private, but extensively dependent upon public interventions, subsidies, risk-mitigation and legal privileges. The state does not in fact represent the sovereign will of the people, nor does the market enact the autonomous preferences of small investors and consumers. Rather, the system is a more or less closed oligopoly of elite insiders. The political and personal connections between the largest corporations and government are so extensive as to amount to collusion. Transparency is minimal, regulation is corrupted by industry interests, accountability is a politically manipulated show, and the self-determination of the citizenry is mostly confined to choosing between Tweedledum and Tweedledee at election time. The state in many countries amounts to a junior partner of clans, mafia-like-structures or dominant ethnies, in other countries he amounts to a junior partner of in this market fundamentalist project. It is charged with advancing privatization, deregulation, budget cutbacks, expansive private property rights and unfettered capital investment. The state provides a useful fig leaf of legitimacy and due process for the market’s agenda, but there is little doubt that private capital has overwhelmed democratic, non-market interests except at the margins. State intervention to curb market excesses is generally ineffective and pallliative. They don’t touch the underlying problem, moreover – they often legitimize the procedures and principles of the market. In consequence: Market forces dominate most agendas. In the U.S., corporations have even been recognized as legal “persons” entitled to give unlimited amounts of money to political candidates. The presumption that the state can and will intervene to represent the interests of citizens is no longer credible. Unable to govern for the long term, captured by commercial interests and hobbled by stodgy bureaucratic structures in an age of nimble electronic networks, the state is arguably incapable of meeting the needs of citizens as a whole. The inescapable conclusion is that democratic governance in its own forms is no longer possible – and that conventional political discourse, itself a aging artifact of another era, is incapable of naming our problems, imagining alternatives and reforming itself. This, truly, is why the commons has such a potentially transformative role to play. It is a discourse that transcends and remakes the categories of the prevailing political and economic order. It provides us with a new socially constructed order of experience, an elemental political worldview and grand narrative enshrined in language. The commons as a new narrative identifies the relationships that should matter and sets forth a different operational logic. It validates new schemes of human relations, production and governance – one might call it “commonance,”or the governance of the commons. The commons provides us with the ability to name and then help constitute a new order. We need a new language that does not insidiously replicate the misleading fictions of the old order – for example, that market growth will eventually solve our social ills or that regulation will curb the world’s proliferating ecological harms. We need a new discourse and new social practices that assert a new grand narrative, a different constellation of operating principles and a more effective order of governance. Seeking a discourse of this sort is not a fanciful whim. It is an absolute necessity. And, in fact, there is no other way to bring about a new order. Words actually shape the world. By using a new language, the language of the commons, we immediately begin to create a new culture. We can assert a new order of resource stewardship, right livelihood, social priorities and collective enterprise. The transformational language of the commons As the corruption of the market/state duopoly has deepened, our very language for identifying problems and imagining solutions has been compromised. The snares and deceptions embedded in our prevailing political language go very deep. Such dualisms as “public” and “private,” and “state” and “market,” and “nature and culture,” for example, are taken as self-evident. As heirs of Descartes, we are accustomed to differentiating “subjective” from “objective,” and “individual” from “collective” as polar opposites. But such polarities are lexical inheritances that are increasingly inapt as the two poles in reality blur into each other. And yet they continue to profoundly structure how we think about contemporary problems and what spectrum of solutions we regard as plausible. Words have performative force. They make the world. In the very moment that we stop talking about business models, efficiency and profitability as top priorities, we stop seeing ourselves as homo economicus and as objects to be manipulated by computer spreadsheets. We start seeing ourselves as commoners in relationship to others, with a shared history and shared future. We start creating a culture of stewardship and co-responsibility for our commons resources while at the same time defending our livelihoods. This new language situates us as interactive agents of larger collectivities. Our participation in these larger wholes (local communities, online affinity groups, inter-generational traditions) does not eradicate our individuality, but it certainly shapes our preferences, outlooks, values and behaviors: who we are. A key revelation of the commons way of thinking is that we humans are not in fact isolated, atomistic individuals. We are not amoebas with no human agency except hedonistic “utilitarian preferences” that are expressed in the marketplace. No: We are commoners – creative, distinctive individuals inscribed within larger wholes. We may have many unattractive human traits fueled by individual fears and ego, but we are also creatures entirely capable of self-organization, cooperation, a concern for fairness and social justice, and sacrifice for the larger good and future generations. The commons helps us recognize, elicit and strengthen these propensities. It challenges us to transcend the obsolete dualisms of market culture and its mechanistic mindset. It asks us to think about the world in more organic, holistic and long-term ways. We can then begin to see that the way one person behaves affects others, and even the entire collective. We see that my personal unfolding depends upon the unfolding of others, and theirs upon mine. We see that we mutually affect and help each other as part of a larger, holistic social organism. Complexity theory has identified simple principles that govern the coevolution of species in complex ecosystems. The commons takes such lessons to heart and asserts that we humans co-evolve with and co-produce each other. We do not exist in grand isolation from our fellow human beings and nature. The myth of the “self-made man” that market culture celebrates is absurd – a self-congratulatory delusion that denies the critical role of family, community, networks, institutions and nature in making our world. Many of the pathologies of the contemporary economy are built upon this deep substrate of erroneous language. Or more precisely, the elite guardians of the market/state find it useful to employ such misleading categories. The corporation in the U.S. and many other nations, for example, likes to cast itself as a “private” entity that hovers above much of the real-world and its problems. Its purpose is simply to minimize its costs, maximize its sales, and so earn profits for its investors. This is its institutional DNA. It is designed to ignore countless social and environmental harms (primly described by economists as “externalities”) and relentlessly pursue infinite growth. And so it is that language of capitalism validates a certain set of purposes and power relationships, and projects them into the theaters of our minds. The delusions of endless growth and consumption are encoded into the very epistemology of our language and internalized by people. It is only in recent years that large masses of people have understood the alarming real-world consequences of this cultural model and way of thinking: an globally integrated economy dedicated to the proposition that humans must indefinitely exploit, monetize and financially abstract a finite set of natural resources (oil, minerals, forests, fisheries, water). The rise of Peak Oil and global warming (not to mention other ecosystem declines) suggest that this vision is a time-limited fantasy. Nature has real limits. The drama of the next decade will revolve around whether capitalism can begin to recognize and respect these inherent limits. The epistemological premises of “democratic capitalism” extend to information and culture as well. But here, in order to wring maximum profit from intangibles (words, music, images), the logic is inverted. Instead of treating a finite resource, nature, as infinite and without price, here, the corporation demands that an essentially infinite resource, culture and information, be made finite and scarce. That is the chief purpose of extending the scope and terms of copyright and patent law – to make information and culture artificially scarce so that they can then be treated as private property and sold. This imperative has become all the more acute now that digital technologies have made the reproduction of information and creative works easy and essentially free, and in doing so undermined the customary business models that made books, film and music artificially scarce. The commons – a vehicle for meeting everyone’s basic needs in a roughly equitable way – is being annexed and disassembled to serve a global a market machine. Nature becomes commodified. Commoners become isolated individuals. Communities of commoners are splintered and reconstituted as armies of consumers and employees. The “unowned” resources of the commons are converted into the raw fodder for market production and sale – and after every last drop of it has been monetized, the inevitable wastes of the market are dumped back into the commons. Government is dispatched to “mop up” the “externalities,” a task that is only irregularly fulfilled because it is so ancillary to neoliberal priorities. The normal workings of The Economy require constant if not expanding appropriations of resources that morally or legally belong to everyone. They must all be transmuted into tradeable commodities. Enclosure is a sublimely insidious process. Somehow an act of dispossession and plunder must be reframed as a lawful, common-sense initiative to advance human progress. For example, the World Trade Organization, which purports to advance human development through free trade, is essentially a system for seizing non-market resources from communities, dispossessing people and exploiting fragile ecosystems with the full sanction of international and domestic law. This achievement requires an exceedingly complicated legal and technical apparatus, along with intellectual justifications and political support. Enclosure must be mystified through all sorts of propaganda, public relations and the co-optation of dissent. This process has been critical in the drive to privatize lifeforms, supplant biodiverse lands with crop monocultures, censor and control Internet content, seize groundwater supplies to create proprietary bottled water, appropriate indigenous knowledge and culture, and convert self-reproducing agricultural crops into sterile, proprietary seeds that must be bought again and again. Through such processes, the very idea of “The Economy” has been constructed, complete with dualisms about what matters (things that bear prices or affect prices) and what doesn’t (things that have intrinsic, qualitative, moral or subjective value). Over time, The Economy comes to be seen as a universal, ahistorical, entirely natural phenomenon, a fearsome Moloch that somehow preexists humanity and exists beyond anyone’s control. This image begins to express the nightmare of enclosure that afflicts so much of the world – a world where natural ecological processes, communities and vernacular culture have no legal protection or cultural respect. The commons as generative A major point of the commons (discourse), then, is to help us “get outside” of the dominant discourse of the market economy and help us represent different, more wholesome ways of being. It allows us to more clearly identify the value of inalienability – protection against the marketization of everything. Relationships with nature are not required to be economic, extractive and exploitative; they can be constructive and harmonious. For people of the global South, for whom the commons tends to be more of a lived, everyday reality than a metaphor, the language of the commons is the basis for a new vision of “development.” The commons can play this role because it describes a powerful value proposition that market economics ignores. Historically, the commons has often been regarded as a wasteland, a res nullius, a place having no owner and no value. Notwithstanding the long-standing smear of the commons as a “tragedy,” the commons, properly understood, is in fact highly generative. It creates enormous stores of value. The “problem” is that this value cannot simply be collapsed into a single scale of commensurable, tradeable value – i.e., price – and it occurs through processes that are too subtle, qualitative and long-term for the market’s mandarins to measure. The commons tends to express its bounty through living flows of social and ecological activity, not fixed, countble stocks of capital and inventory. The generativity of commons stewardship, therefore, is not focused on building things or earning returns on investment, but rather on ensuring our livelihoods, the integrity of the community, the ongoing flows of value-creation, and their equitable distribution and responsible use. Commoners are diverse among themselves, and do not necessarily know in advance how to agree upon or achieve a shared goals The only practical answer, therefore, is to open up a space for robust dialogue and experimentation. There must be room for commoning – the social practices and traditions that enable a people to discover, innovate and negotiate new ways of doing things for themselves. In order for the generativity of the commons to manifest itself, it needs the “open space” for a bottom-up initiatives to occur in interaction with the resources at hand. In this way, citizenship and governance are blended and reconstituted. Creating an architecture of law and policy to support the commons The viability of bottom-up commons, however, often depends upon supportive institutions, policy regimes and law. As we see in the essays of Part V, this is the new frontier for the commons sector: developing new bodies of law and policy to facilitate the practices of commoning on the ground. For this, the state must play a more active role in sanctioning and facilitating the functioning of commons, much as it currently sanctions and facilitates the functioning of corporations. And commoners must assert their interests in politics and public policy to make the commons the focus of innovations in law. There is a simple, practical reason for developing this theater of action. As the dysfunctionalities of the state become more evident – as seen in its inability to solve the financial crisis or curb ecological destruction — the state has an affirmative interest in helping commons perform tasks that it cannot. It is important that the state begin to recognize the varieties of collective property regimes (an indigenous landscape, a local agricultural system, an online community) and empower people to be co-proprietarians and co-stewards of their commons as a matter of law. For too long commons have been marginalized or ignored in public policy, forcing commoners to develop their own private-law “work-arounds” or sui generis legal regimes in order to establish collective legal rights. Examples include the General Public License for free software, which assures its access and use by anyone and land trusts, which establish tracts of land as commons to be enjoyed by all yet owned as private property (“property on the outside, commons on the inside”). Reference Rost essay? The future of the commons would be much brighter if the state could begin to provide formal charters and legal doctrines to recognize the collective interests and rights of commoners. There is also a need to reinvent market structures so that the old, centralized corporate structures of capitalism do not dominate, and squeeze out, the more locally responsive, socially mindful business alternatives (a trend that the Solidarity Economy movement has been stoutly resisting). In recent years there has been a proliferation of commons-friendly businesses models in which enterprises subordinate their interests in profit maximization to the long-term interests of their communities, producers and consumers. Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs), the Slow Food movement, the Slow Money movement, the Mietshäuser Syndikat (apartment building trust) in Germany, and fair trade businesses are shining examples. There is an inherent tension in seeding new sorts of commons initiatives, however: They often must work within the existing system of law and policy, which poses a danger of co-optation of the commons and the domestication of its innovations. This is a real danger, yet commons initiatives need not lose their transformative, catalytic potential simply because they work “within the system.” Among commoners, there will invariably be debates about the strategic “purity” of commons-based initiatives, especially those that interact with the marketplace in new ways. Such scrutiny is important. Yet it may also highlight deeper philosophical tensions within the commons movement – namely, that some commoners prefer to have little or no intercourse with markets while others believe that their communities can thrive because of their interactions with markets. This is a creative tension that will never go away, nor should it. But the critical question for commoners to ask is, What is production for? Unlike market capitalism, which requires constant economic growth, the point of the commons is to propagate and extend a commons-based culture. The goal is to meet people’s needs – and to reproduce and expand the commons sector. Throughout history, civilizations have always had a dominant organizational form. In tribal economies, gift exchange was dominant. In pre-capitalist societies such as feudalism, hierarchies prevailed and rewards were allocated on the basis of one’s social status. In our era of capitalism, the market is the primary system fthat or allocating social status, wealth and opportunities for human development. Now that the limitations and dysfunctions of the market system under capitalism are abundantly clear, the question we must confront is whether the commons can become the dominant social form. We believe it is entirely possible to create commons-based innovations that work within existing government systems while helping bring about a new order. We hope that the essays of this book encourage new explorations and initiatives in this direction. This is a rare moment in history in which old, fixed categories of thought are giving way to new possibilities. But any transition to a new paradigm will require that enough people “step into history” and make the new categories of the commons their own. Hope for the future lies in people creating their own distinctive forms of commoning throughout the world, and the gradual emergence and confluence of new social/economic practices. We are hard-wired to cooperate and participate in commons. One might even say that it is our destiny. While the commons may seem odd within the context of 21st Century market culture, it is precisely why the language of the commons is experiencing such a strong resurgence these days: It speaks to something buried deep within us. It prods us to deconstruct the oppressive political culture and consciousness that the market/state duopoly demands, and whispers of new possibilities that only we can actualize. David Bollier is an author, activist, blogger and consultant who spends a lot of time exploring the commons as a new paradigm of economics, politics and culture. He recently co-founded the Commons Strategies Group, a consulting project that works to promote the commons internationally. He was Founding Editor of Onthecommons.org and a Fellow of On the Commons from 2004 to 2010. He has written eleven books and co-edited a twelfth . He has two forthcoming books: The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State (September 2012, Levellers Press), co-edited with Silke Helfrich; and Green Governance: Ecological Survival, Human Rights and the Commons (early 2013, Cambridge University Press), co-authored with Professor Burns H. Weston. His blog is http://bollier.org |

Read |

| October 25, 2012 | by Rajesh Makwana, Stwr.org, Countercurrents.org The following article is based on a presentation by Share The World’s Resources for the World Public Forum ‘Dialogue of Civilisations’ 10th Anniversary Conference, Rhodes, October 2012 The earth’s ecological problems stem largely from our collective failure to share. That might seem like an overly simplistic statement, but it is now increasingly evident that only by sharing the world’s resources more equitably and sustainably will we be able to address both the ecological and social crisis we face as a global community. The principle of sharing has always formed the basis of social relationships in societies across the world. We all know from personal experience that sharing is central to family and community life, and the importance of sharing is also a key component of many of the world’s religions. Moreover, it is becoming apparent through a growing body of anthropological and biological evidence that human beings are naturally predisposed to cooperate and share in order to improve our collective wellbeing and maximise our chances of survival. In fact, sharing is far more prevalent in society than people often realise. In a recent report, we identified the many emerging and existing forms of what is being popularly termed the ‘sharing economy’. This includes collaborative consumption, knowledge sharing websites like Wikipedia, and many other forms of cooperative and peer2peer enterprises. Although not commonly recognised as such, systems of social welfare can also be considered one of the most advanced forms of economic sharing ever established in the modern world. Given the importance of the principle of sharing in human life, it is logical to assume that it should play an important role in the way we organise economies and manage the world’s resources. But this is not the case. Instead, we have created an economic system based on ideologies that are entirely opposed to the principle of sharing. For decades, mainstream economists and policymakers have based their decision-making on a distorted understanding of what it means to be human: that people are selfish, acquisitive, individualistic and competitive by nature – the concept of homo economicus. These notions are still used to justify the exaggerated role that market forces play in organising societies. As we know, neoliberal ideology continues to dominate policymaking across the world - characterised by the privatisation of public assets and the shared ‘commons’, the deregulation and liberalisation of markets, the endless pursuit of economic growth and the overconsumption of natural resources. The consequences of our failure to share As a result of failing to put the principle of sharing at the centre of policymaking, we now face a multitude of environmental crises, from climate change and pollution to deforestation and peak energy – the list is long. Underpinning these multiple ecological crises is the failure of governments to achieve a balance between consumption levels and the Earth’s life-supporting capacity. As the WWF have painstakingly demonstrated, humanity currently consumes 50 percent more natural resources than the earth can sustainably produce, which means we already require the equivalent of one and a half planets to support our consumption levels. This calculation doesn’t even take into account the massive growth in consumption that is widely predicted to take place over coming decades, in which the global ‘middle class’ is expected to grow from under 2 billion consumers today to nearly 5 billion by 2030. Clearly, the ecological consequences of increased consumption across the world will be severe. According to research by the Stockholm Resilience Centre, humanity has already transgressed three out of nine key planetary boundaries – climate change, biological diversity as well as nitrogen and phosphorous cycles. But our failure to share resources has also resulted in severe social consequences which cannot be divorced from any discussion about the environment. Ecological chaos, poverty and inequality are related outcomes of an ill-managed world system, and they require simultaneous attention – a fact embodied in the contemporary dialogue on sustainable development. There are massive differences in the consumption patterns and carbon emissions of people living in rich and poor countries. A small proportion of the world’s population – around 20 percent – consumes the vast majority of the world’s resources. According to Oxfam, excessive consumption by the wealthiest 10 percent of the world’s population poses the biggest threat to the environment today. At the same time, the poorest 20 percent of the world’s population do not have access to the basic resources they need to survive. Around a billion people are officially classified as hungry, and almost half of the developing world population is trying to survive on less than $2 a day. Statistics from the World Health Organisation reveal that over 40,000 people die every single day from a lack of access to those resources that many of us take for granted. This is perhaps the starkest illustration of the human impact of our failure to share. Overcoming the barriers to progress Given the urgency of the ecological and social situation, why are we still failing to manage the world’s resources in a more equitable and sustainable way? Every year, numerous international conferences and negotiations take place, but the international community has not managed to implement binding limits on CO2 emissions. We have failed to curb unsustainable patterns of resource consumption. And we have by no means succeeded in ending poverty or paving the way for more sustainable development. In the meanwhile, endless reports are published that recommend a sensible path for reforming the global economy, but are not taken seriously by policymakers. Nothing seems to change. Humanity is at an impasse; we seem unable to overcome the vested interests and structural barriers to progress that we face. For too long, governments have put profit and growth before the welfare of all people and the sustainability of the biosphere. Public policy under the influence of neoliberalism has created a world economy that is structurally dependent upon unsustainable levels of production and consumption for its continued success. Overcoming the vested interests that continue to block progress on restructuring the world economy has long been regarded by campaigners as the most significant challenge of the 21st century. Given the scale of the task ahead and the extensive international negotiations these reforms would involve, it is impossible at this stage to put forward a blueprint of the specific policies and actions governments need to take. But in order to inspire public support for transformative change, it is imperative that we outline a bold vision of how and why these reforms should be based firmly on the principle of sharing. Sharing the world’s resources equitably and sustainably is arguably the most pragmatic way of simultaneously addressing both the ecological and social crises we face. Envisioning a global sharing economy Two basic elements remain fundamental to the proper functioning of a ‘global sharing economy’. The first element is for the international community to recognise that natural resources form part of our shared commons, and should therefore be held in trust for the benefit of all. This important reconceptualization would enable humanity to move away from today’s private and state ownership models, and towards a new form of resource management based on non-ownership and trusteeship. A precedent for sharing natural resources is already well established. An existing principle in international law known as the ‘common heritage of humankind’ enables certain cultural and natural resources to be protected from exploitation - from both the state and private sector - by holding them in trust for future generations. This principle is an important feature in a number of international treaties that have taken shape under the auspices of the United Nations. There are of course many options available for how such a trust could be organised on a global level to incorporate the full range of renewable and non-renewable resources, including fossil fuels. For example, a number of proposals already exist such as those outlined by James Quilligan, Peter Barnes, or Peter Brown and Geoffrey Garver in their book ‘Right Relationship’, among others. Essentially, a Global Commons Trust would embody the principle of sharing on a global scale, and it would enable the international community to take collective responsibility for managing the world’s resources. With resources held in trust for all, it would be much easier to implement the second element required to establish a global sharing economy, which is to equalise global consumption levels so that all human beings can flourish within ecological limits. To achieve this, over-consuming countries need to significantly reduce their resource use, while developing countries must be able to increase theirs until a convergence in global per capita consumption levels is eventually reached. The real challenge is reducing consumption levels in industrialised nations, and many proposals already exist for how to achieve this. For example, it is clear that resource management would need to be at the forefront of policymaking, and consumption-led economic growth can no longer be the goal of government policy. Much would also need to be done to dismantle the culture of consumerism; and investment must shift to building and sustaining a low-carbon infrastructure. With both of these key elements in place (trusteeship of shared resources and reduced global consumption), natural resources would be accessible to people in all countries, consumed within planetary limits and preserved for future generations. The key to change is the rise of the people But how will these changes happen? Regardless of the specific policies employed, the world still lacks a broad-based acceptance of the need for planetary reconstruction. Without a global movement of ordinary people that share a collective vision of change, it will remain impossible to overcome the influence of neoliberal ideology and the vested interests mentioned above. However, the historic events of 2011 provided concrete evidence of the potential power of a united ‘people’s voice’. The world witnessed millions of people in diverse countries declaring their needs and highlighting issues of social and economic inequality, greed, financial corruption and the undue influence of corporations on government. The Arab Spring demonstrated the awesome power of a focussed and directed public opinion. And in city squares across the developed world, Occupy, the Indignados and a host of other people’s movements focussed the world’s media on the plight of the ‘99%’ and gained widespread public support in the process. The rapid spread of these mass demonstrations reflects a growing recognition of humanity’s innate unity and propensity to share, and they pay testimony to the combined power of engaged citizens. But if public opinion is to make transformative change a reality, a crucial next step is to adopt a common and inclusive platform for change on a global scale. In other words, we need a planetary Tahrir Square. Social injustice and ecological crises must be recognised as inextricable parts of the same problem: our failure to share the world’s resources in a way that benefits all people and preserves the biosphere. A universal call for sharing has the potential to unite both environmentalists and those campaigning for global justice, paving the way to a more just, sustainable and peaceful world. Rajesh Makwana is the director of Share The World's Resources and can be contacted at rajesh(at)stwr.org. This work is published under a Creative Commons License. When reproducing this item, please attribute Share The World’s Resources as the source and include a link to its unique URL. For more information, please see our Copyright Policy. |

Read |

| October 18, 2012 | by Marianne de Nazareth, Countercurrents.org

The world according to the new TEEB report ( The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity) released at the 11th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention for Biological Diversity (COP11) in Hyderabad needs to realise the vital economic and environmental role of wetlands, to halt further degradation and loss. Countries across the world need to realise the key role that rapidly diminishing wetlands play in supporting human life and biodiversity. Water security is widely regarded as one the key natural resource challenges currently facing the world. Human drivers of ecosystem change, including destructive extractive industries, unsustainable agriculture and poorly managed urban expansion, are posing a threat to global freshwater biodiversity and water security for 80 per cent of the world’s population. Global and local water cycles are strongly dependent on healthy and productive wetlands, which provide clean drinking water, irrigation for agriculture, and flood regulation, as well as supporting biodiversity and propping up industries such as fisheries and tourism in many countries. Yet, despite the high value of these ecosystem services, wetlands continue to be degraded or lost at an alarming pace. Half of the world’s wetlands were lost during the twentieth century – due mainly to factors such as intensive agriculture, unsustainable water extraction for domestic and industrial use, urbanization, infrastructure development and pollution. The continuing degradation of wetlands is resulting in significant economic burdens on communities, countries and businesses. Inland wetlands cover at least 9.5 million km (about 6.5 per cent of the Earth’s land surface), while inland and coastal wetlands together cover a minimum of 12.8 million km. Between 1900 and 2003, the world lost an estimated 50 per cent of its wetlands, while recent coastal wetland loss in some places, notably East Asia, has been up to 1.6 per cent a year. This has led to situations such as the 20 per cent loss of mangrove forest coverage since 1980. The main pressures on wetlands come from: Habitat loss, for example through wetland drainage for agriculture or infrastructure developments, driven by population growth and urbanization; Such pressures threaten wetlands’ natural infrastructure, which delivers a wider range of services and benefits than corresponding man-made infrastructure at a lower cost. Wetlands are a key factor in the global water cycle and in regulating local water availability and quality. They contribute to water purification, de-nitrification and detoxification, as well as to nutrient cycling, sediment transfer, and nutrient retention and exports. Wetlands can also provide waste water treatment and protection against coastal and river flooding. For example, The Catskill / Delaware watershed provides about 90 per cent of the water used by New York City citizens. In 1997, a study showed that building a new water treatment plant would cost between US$6 and US$8 billion, whereas ensuring good water quality through measures to reduce pollution in the watershed would only cost US$1.5 billion. This study led to programmes to promote the sustainability of the watershed. Wetlands also play a key role in the provision of food, and habitats and nurseries for fisheries. One example is the Amu Darya delta in Uzbekistan where Intensification and expansion of irrigation activities left only 10 per cent of the original wetlands. Yet a pilot restoration project initiated in the delta, with the support of community, government and donors which has led to increased incomes, more cattle, more hay production for use and sale, and an increase in fish consumption of 15 kilogrammes per week per family. Wetlands can also be an important tourism and recreation sites and support local employment. For example In the Ibera Marshes in Argentina, conservation-based tourism activities have revived the economy of Colonia Carlos Pellegrini, near the Ramsar Site “Lagunas y Esteros del Iberá”, creating new jobs and allowing local inhabitants stay employed in the town rather than migrate to cities to look for work. Around 90 per cent of the population now works in the tourism sector. In order to favour local employment, the site managers provide local rangers and guides with training on working with guiding tourists. In addition, local communities receive support to establish municipal nature trails.

Wetlands also provide climate regulation, climate mitigation and adaptation, and carbon storage – for example in peatlands, mangroves and tidal marshes. Peatlands cover 3 per cent of the world’s land surface, about 400 million hectares (4 million km2), of which 50 million hectares are being drained and degraded, producing the equivalent of 6 per cent of all global Carbon Dioxide emissions. While vegetative wetlands occupy only 2 per cent of seabed area, they represent 50 per cent of carbon transfer from oceans to sediments, often referred to as ‘Coastal Blue Carbon’. National and international policy makers should: Integrate the values of water and wetlands into decision making – for policies, regulation and land-use planning, incentives and investment, and enforcement; Regulate to protect wetlands from pressures that do not lead to improvements in public goods and overall societal benefits; Regulate to ensure that wetland ecosystem services options and benefits are fully considered as solutions to land- and water-use management objectives and development; Commit to and develop improved measurement and address knowledge gaps – using biodiversity and ecosystem services indicators and environmental accounts. “Policies and decisions often do not take into account the many services that wetlands provide – thus leading to the rapid degradation and loss of wetlands globally,” said UN Under-Secretary General and UN Environment Programme Executive Director Achim Steiner. “There is an urgent need to put wetlands and water-related ecosystem services at the heart of water management in order to meet the social, economic and environmental needs of a global population predicted to reach 9 billion by 2050,” he added. “In 2008 the world’s governments at the Ramsar Convention’s 10th Conference of Parties stressed that for water management carrying on ‘business as usual’ is no longer an option”, said the Ramsar Convention’s Deputy Secretary General, Nick Davidson. “This report tells us bluntly just how much more important than generally realized are our coastal and inland wetlands: for the huge value of the benefits they provide to everyone, particularly in continuing to deliver natural solutions for water - in the right quantity and quality, where and when we need it. If we continue to undervalue wetlands in our decisions for economic growth, we do at our increasing peril for people’s livelihoods and the world’s economies,” he added. (Marianne de Nazareth is Independent media professional and adjunct faculty St. Joseph’s College and COMMITS, Bangalore) |

Read |

| October 17, 2012 | by Thom Hartmann, Op-Ed News, AlterNet In the past - diseases like tuberculosis and malaria have been number one health concerns around the world. But not anymore. In today's world - globalization is the number one health risk facing humanity. A new study released this week by the Blacksmith Institute reveals, for the first time ever, the impact of industrial pollutants on communities across the planet. It found that industrial waste dump sites containing lead, mercury, chromium, pesticides, and other toxic horrors, poison more than 125 million people in 49 different low and middle income nations around the planet. And the authors of the study say this is a very conservative estimate - and likely even more people are sickened by this rampant industrial pollution. In fact, the report says that industrial pollution is now a bigger global health problem for the world than malaria and tuberculosis. Just look at what's happening in places like Zamfara, Nigeria. It's a state without children - or very few children walking around. Why? because hundreds of children who work in gold mines are exposed to high levels of lead. Back in March of 2010 - the organization Doctors Without Borders arrived on the scene in Zamfara - and found that hundreds of children had died from lead poisoning - and thousands more were diseased by it. Mortality rates in some villages were as high as 43%. This is a genocide carried out by transnational corporations that have no restraints on how they operate in what were once sovereign nations. That's the consequence of globalism. Plain and simple - globalization is the empowering of transnational corporations - and the neutering of sovereign governments to keep their populations safe from these transnational corporate behemoths. Globalization tears down borders across the planet - giving corporations free rein to move about the world and set up shop in nations wherever governments are the weakest, wherever there's the least amount of regulation, and wherever workers are willing to work for practically nothing. And since most transnational corporations are far wealthier than nations in the developing world - they just move in and take over, enslaving local populations and using local communities as garbage dumps. You see - when you leave corporations completely unrestrained - when you leave their drive for neverending profits unchecked - then they stop at nothing to satisfy their greed. If it means they'll save a few million bucks a year - then they'll dump battery acid all over a playground if you let them. They are profit making machines - without compassion. And - as Richard Fuller the President of the BlackSmith Report warned - it's only going to get worse. He said: "Life-threatening pollution will likely increase as the global economy exerts an ever-increasing pressure on industry to meet growing demands. The damage will be greatest in many low and middle-income countries, where industrial pollution prevention regulations and measures have not kept pace." And it's not just the developing world that's being poisoned - it's the United States, too. According to that same report - there are as many as 300,000 toxic dump sites in the United States alone. And that doesn't include the over 400,000 fracking wells around the United States. Industry funded scientists say that fracking is perfectly safe - however - study after study shows its deadly. Just last week - a study on fracking found that the closer residents live to fracking wells - the more they suffered from symptoms of throat irritation and sinus infections. Even their pets suffered from the same ailments - and in some cases died. Water and air samples in areas near fracking wells were also found to contain high levels of chemicals associated with fracking. Americans could have been protected from these dangers of industrial fracking - unfortunately Dick Cheney - being a loyal corporate globalist - was able to carve out an exemption for the fracking industry in 2004 - that keeps the EPA from being able to regulate fracking under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Since then - fracking has exploded - and so too have diseases associated with fracking. Yet Republicans want this epidemic to continue. As Rick Perry so eloquently recited the mantra of the corporate globalists: American needs Freedom from "over-taxation, freedom from over-litigation and freedom from over-regulation." That means freedom for chemical companies to dump pesticides in our backyards - freedom for fracking companies to inject toxins in our drinking water - and freedom for oil companies to spew unlimited amounts of carbon into our air to accelerate global climate change. These guys want the new Zamfara, Nigeria to be in Pennsylvania. The point of all this is - corporate globalism will kill us all. Without government protections in place to keep "we the people" safe from industrial malfeasance - then say hello to ever increasing cases of cancer, asthma, autism, you name it. This struggle is nothing new - in fact - it's as old as time. It's the struggle between organized people - or governments - and organized money - or transnational corporations. We rebelled against transnational corporate power in the form of the East India Tea Company back in 1773, leading to our national independence a few years later. And today - almost 330 years later - we need another revolution against these transnational corporate killers. |

Read |

| October 30, 2012 | by George Lakoff,

Yes, global warming systemically caused Hurricane Sandy -- and the Midwest droughts and the fires in Colorado and Texas, as well as other extreme weather disasters around the world. Let's say it out loud, it was causation, systemic causation. Systemic causation is familiar. Smoking is a systemic cause of lung cancer. HIV is a systemic cause of AIDS. Working in coal mines is a systemic cause of black lung disease. Driving while drunk is a systemic cause of auto accidents. Sex without contraception is a systemic cause of unwanted pregnancies.

There is a difference between systemic and direct causation. Punching someone in the nose is direct causation. Throwing a rock through a window is direct causation. Picking up a glass of water and taking a drink is direct causation. Slicing bread is direct causation. Stealing your wallet is direct causation. Any application of force to something or someone that always produces an immediate change to that thing or person is direct causation. When causation is direct, the word cause is unproblematic.

Systemic causation, because it is less obvious, is more important to understand. A systemic cause may be one of a number of multiple causes. It may require some special conditions. It may be indirect, working through a network of more direct causes. It may be probabilistic, occurring with a significantly high probability. It may require a feedback mechanism. In general, causation in ecosystems, biological systems, economic systems, and social systems tends not to be direct, but is no less causal. And because it is not direct causation, it requires all the greater attention if it is to be understood and its negative effects controlled.

Above all, it requires a name: systemic causation.

Global warming systemically caused the huge and ferocious Hurricane Sandy. And consequently, it systemically caused all the loss of life, material damage, and economic loss of Hurricane Sandy. Global warming heated the water of the Gulf and Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, resulting in greatly increased energy and water vapor in the air above the water. When that happens, extremely energetic and wet storms occur more frequently and ferociously. These systemic effects of global warming came together to produce the ferocity and magnitude of Hurricane Sandy.

The precise details of Hurricane Sandy cannot be predicted in advance, any more than when, or whether, a smoker develops lung cancer, or sex without contraception yields an unwanted pregnancy, or a drunk driver has an accident. But systemic causation is nonetheless causal.

Semantics matters. Because the word cause is commonly taken to mean direct cause, climate scientists, trying to be precise, have too often shied away from attributing causation of a particular hurricane, drought, or fire to global warming. Lacking a concept and language for systemic causation, climate scientists have made the dreadful communicative mistake of retreating to weasel words. Consider this quote from "Perception of climate change," by James Hansen, Makiko Sato, and Reto Ruedy, Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences:

...we can state, with a high degree of confidence, that extreme anomalies such as those in Texas and Oklahoma in 2011 and Moscow in 2010 were a consequence of global warming because their likelihood in the absence of global warming was exceedingly small.

The crucial words here are high degree of confidence, anomalies, consequence, likelihood, absence, and exceedingly small. Scientific weasel words! The power of the bald truth, namely causation, is lost.

This no small matter because the fate of the earth is at stake. The science is excellent. The scientists' ability to communicate is lacking. Without the words, the idea cannot even be expressed. And without an understanding of systemic causation, we cannot understand what is hitting us.

Global warming is real, and it is here. It is causing -- yes, causing -- death, destruction, and vast economic loss. And the causal effects are getting greater with time. We cannot merely adapt to it. The costs are incalculable. What we are facing is huge. Each day, the amount of extra energy accumulating via the heating of the earth is the equivalent of 400,000 Hiroshima atomic bombs. Each day!

Because the earth itself is so huge, this energy is distributed over the earth in a way that is not immediately perceptible by our bodies -- only a fraction of a degree each day. But the accumulation of total heat energy over the earth is increasing at an astronomical rate, even though the temperature numbers look small locally -- 0.8 degrees Celsius so far. If we hit 2.0 degrees Celsius, as we may before long, the earth -- and the living things on it -- will not recover. Because of ice melt, the level of the oceans will rise 45 feet, while huge storms, fires, and droughts get worse each year.

The international consensus is that by 2.0 degrees Celsius, all civilization would be threatened if not destroyed.

What would it take to reach a 2.0 degrees Celsius increase over the whole earth? Much less than you might think. Consider the amount of oil already drilled and stored by Exxon Mobil alone. If that oil were burned, the temperature of the earth would pass 2.0 degree Celsius, and those horrific disasters would come to pass.

The value of Exxon Mobil -- its stock price -- resides in its major asset, its stored oil. Because the weather disasters arising from burning that oil would be so great that we would have to stop burning. That's just Exxon Mobil's oil. The oil stored by all the oil companies everywhere would, if burned, destroy civilization many times over.

Another way to comprehend this, as Bill McKibben has observed, is that most of the oil stored all over the earth is worthless. The value of oil company stock, if Wall St. were rational, would drop precipitously. Moreover, there is no point in drilling for more oil. Most of what we have already stored cannot be burned. More drilling is pointless.

Are Bill McKibben's and James Hansen's numbers right? We had better have the science community double-check the numbers, and fast.

Where do we start? With language. Add systemic causation to your vocabulary. Communicate the concept. Explain to others why global warming systemically caused the enormous energy and size of Hurricane Sandy, as well as the major droughts and fires. Email your media whenever you see reporting on extreme weather that doesn't ask scientists if it was systemically caused by global warming.

Next, enact fee and dividend, originally proposed by Peter Barnes at Sky Trust and introduced as Senate legislation as the KLEAR Act by Maria Cantwell and Susan Collins. More recently, legislation called fee and dividend has been proposed by James Hansen and introduced in the House by representatives John B, Larson and Bob Inglis.

Next. Do all we can to move to alternative energy worldwide as soon as possible. George Lakoff is Goldman Distinguished Professor of Cognitive Science and Linguistics at the University of California at Berkeley. He is the author of The California Democracy Act, a grassroots California ballot initiative now organizing public support at camajorityrule.com. He is also the co-author (with Elisabeth Wehling) of The Little Blue Book: The Essential Guide to Thinking and Talking Democratic. |

Read |

| October 22, 2012 | by Joseph Nevins, GlobalPossibilities.org, AlterNet