1. Introduction

2. Global Community

2.1 Definition and global concepts

2.2 Establishment of global communities

3. Global politics

4. Global Community Earth Government (GCEG)

5. Global citizenship criteria

6. Statement of rights, responsibilities, and accountabilities of the Global Community citizens

7. Scale of Human and Earth Rights

8. The Global Constitution

9. Global citizens responsibility and accountability

9.1 Public accountability of autonomous public organizations

9.2 Ideas about accountability

9.3 Conflicts within components of accountability

9.4 Role of the Secretary of the Global Council

9.5 Recommendations to modernize the Secretary’s role, and reinforce the integrity of the centre

9.6 Responsibility, accountability and the role of Deputy Ministers in the GCEG

9.7 Ministerial responsibility and the Global Financial Administration Act: the constitutional obligation to account for GCEG spending

9.8 The fundamental principles underlying responsible global parliamentary government

9.9 The evolving nature of GCEG

9.10 Factors that have affected and altered the nature of government and governance in the world over the last 150 years

9.11 Political actors versus professional actors

9.12 The relationship between the exempt staff serving the President and the public servants

9.13 The interface between political actors and professional actors

9.14 The multiple responsibilities and accountabilities of Deputy Ministers

9.15 Mechanisms for political and professional financial accountability

9.16 The Global Parliament procedure and merits

9.17 The responsibilities of an accounting officer

9.18 The roles and accountabilities of Deputy Ministers/Accounting Officers

9.19 Ministerial responsibility and the Global Financial Administration Act: the Constitutional obligation to account for GCEG spending

9.20 Ministerial responsibility in GCEG

9.21 The constitutional basis of global ministerial responsibility

9.22 The statutory basis of financial accountability

9.23 Responsibility, accountability, liability

9.24 Recent statements on responsibility and accountability

9.25 Accountability of Deputy Ministers

9.26 Deputy Ministers’ direct accountability

9.27 Deputy Ministers’ indirect accountability

9.28 Conflict resulting from Deputy Ministers’ accountabilities

9.29 The problem known as “regulation within government”

9.30 Alternative patterns of governance and accountability

9.31 What might be the best model of policy administration?

9.32 Performance management

9.33 The Global Community interest

10. More responsible actions to improve the system of government

10.1 List "A"11. Corporate global citizens responsibility and accountability

10.2 End the influence of money in global politics

10.3 Toughen the Lobbyists Registration Act

10.4 Ban secret donations to political candidates

10.5 Make qualified government appointments

10.6 Clean up government polling and advertising

10.7 Clean up the procurement of government contracts

10.8 Provide real protection for whistleblowers

10.9 Ensure truth in budgeting with a Global Parliamentary Budget Office

10.10 Strengthen the power of the Auditor General

10.11 Strengthen the role of the GCEG Ethics Commissioner

10.12 Strengthen Access to Information legislation

10.13 Strengthen auditing and accountability within departments

12. Corporate global citizens ethics

13. Preventive actions against polluters

14. Business and trade responsibility and accountability: new way of doing business and trade for everyone

![]()

* practicing tolerance and living together in peace and harmony with one another as neighbours,

* promoting the economic and social advancement of all peoples,

* maintaining peace and security in the world by using negotiations and peaceful means,

* finding unity in diversity with all Life,

* establishing the respect for the life-support system of the planet,

* keeping Earth healthy, productive and hospitable for all people and living things, and

* applying the principle that when there is a need to find a solution to a problem or a concern, a sound solution would be to choose a measure or conduct an action, if possible, which causes reversible damage as opposed to a measure or an action causing an irreversible loss.

* the Global Community today has come to a turning point in history, and that we are on the threshold of new global order leading to an era of peace, prosperity, justice and harmony;

* there is an interdependence of people, nations and all life;

* humanity's abuse of science and technology has brought the Global Community to the brink of disaster through the production of weaponry of mass destruction and to the brink of ecological and social catastrophe;

* the traditional concept of security through military defense is a total illusion both for the present and for future generations;

* misery and conflicts has caused an ever increasing disparity between rich and poor;

* we, as Peoples, are conscious of our obligation to posterity to save the Global Community from imminent and total annihilation;

* the Global Community is One despite the existence of diverse nations, races, creeds, ideologies and cultures,

* the principle of unity in diversity is the basis for a new age when war shall be outlawed and peace prevail; when the earth's total resources shall be equitably used for human welfare; and when basic human and Earth rights, responsibilities and accountabilities shall be shared by all without discrimination; and

* the greatest hope for the survival of life on Earth is the establishment of a democratic Earth Government.

1. maintain international peace and security in conformity with the principles of justice and global law;

2. promote friendly relations among nations, individuals and communities based on:

* respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of Peoples; and

* symbiotical relationships;

3. promote global co-operation to:

* find sound solutions to economic, social, cultural, humanitarian, local and global community problems; and

* establish respect for human and Earth rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.

4. be a home and a global community centre to all nations, people and local communities and help them harmonize their actions to achieve their common goals.

5. promote worldwide awareness of:

a) the "Beliefs, Values, Principles and Aspirations" of Earth Government, which constitute the Preamble and Chapter 1 to Chapter 10 inclusive;

b) global symbiotical relationships amongst people, institutions, cities, provinces and nations of the world, and between Earth Government and all nations, and in the business sector, which constitute Chapters 20.24 and 23.3.2;

c) global societal sustainability, which constitutes Chapter 4.4 of this Constitution;

d) good Earth governance and management, which constitute Chapter 6.3.2 of this Constitution;

e) the Scale of Human and Earth Rights, which constitutes Chapter 10 of this Constitution;

f) the Statement of Rights, Responsibilities and Accountabilities of a Person and of the Global Community, which constitutes Chapter 6.3 of this Constitution;

g) the Criteria to obtain the Global Community Citizenship, which constitutes Chapters 6.1 and 6.2 of this Constitution;

h) consistency between the different policies and activities of Earth Government, which constitutes Chapter 15 of this Constitution; and

i) a global market without borders in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capitals is ensured in accordance with this Constitution, which constitutes Chapter 16 of this Constitution;

j) the new ways of doing business in the world, which constitutes Chapters 16 and 17;

k) the Celebration of Life Day on May 26 of each year, which constitutes Chapter 20.7 of this Constitution;

l) the finding of an Earth flag, which constitutes Chapter 20.8 of this Constitution;

m) the ECO Award, which constitutes Chapter 20.9 of this Constitution;

n) the Portal of the Global Community, which constitutes Chapter 20.10 of this Constitution; and

o) the concept of a Global Dialogue, which constitutes Chapter 20.11 of this Constitution.

Earth Government shall reinforce humanity's new vision of the world throughout the millennium.

Humanity's new vision of the world is about seeing human activities on the planet through:

a) the Scale of Human and Earth Rights;

b) the Statement of Rights, Responsibilities and Accountabilities of a person and the Global Community; and

c) building global symbiotical relationships between people, institutions, cities, provinces and nations of the world.

For the first time in human history, and the first time this millennium, humanity has proposed a benchmark:

* formation of global ministries in all important aspects of our lives

* getting ride of corruption at all levels of government

* the establishment of Global Police to fight against the growing threat to the security of all Peoples, and to fight against global crimes

* the Scale of Human and Earth Rights as a replacement to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

* Statement of Rights, Responsibilities and Accountabilities of a person belonging to 'a global community' and to 'the Global Community'

* an evolved global democracy based on the Scale of Human and Earth Rights and the Global Constitution

* a central organization for Earth management, the restoration of the planet and Earth governance: the Global Community Assessment Centre (GCAC)

* the Earth Court of Justice to deal with all aspects of governance and management of the Earth

* a new impetus given to the way of doing business and trade

* more new, diversified (geographical, economical, political, social, business, religious) symbiotical relationships between nations, communities, businesses, for the good and well-being of all

* proposal to reform the United Nations, NATO, World Trade Organization, World Bank, IMF, E.U., NAFTA, FTAA, and to centralize them under Earth Government, and these organizations will be asked to pay a global tax to be administered by Earth Government

* the Peace Movement of the Global Community and shelving of the war industry from humanity

* a global regulatory framework for capitals and corporations that emphasizes global corporate ethics, corporate social responsibility, protection of human and Earth rights, the environment, community and family aspects, safe working conditions, fair wages and sustainable consumption aspects

* the ruling by the Earth Court of Justice of the abolishment of the debt of the poor or developing nations as it is really a form of global tax to be paid annually by the rich or industrialized nations to the developing nations

* establishing freshwater and clean air as primordial human rights

Back to top of page

Chapter I What Earth Government represents, its "Beliefs, Values, Principles and Aspirations"

The Preamble and Chapter 1 to Chapter 10 inclusive reflect the "Beliefs, Values, Principles and Aspirations" of Earth Government.

Article 1: Establishment of Earth Government

1. Reflecting the will of the Global Community citizens and all Nations to build a common future, this Global Constitution establishes Earth Government, on which Member Nations confer competences to attain objectives they have in common. Earth Government shall coordinate the policies by which Member Nations aim to achieve these objectives.

2. Earth Government shall be open to all Member Nations which respect its values and are committed to promoting them together.

3. Earth Government was first thought out by the Founding Members of the Global Community.

The Global Community organization was first discussed in a report on global changes published in 1990 by Germain Dufour. The report contained 450 policies (workable sound solutions) on sustainable development, and was presented to the United Nations, the Government of Canada, the provincial government of Alberta and several non-profit organizations and scientists. Historically, the Earth Community Organization (ECO) was called the Global Community organization. The name was changed during the August 2000 Global Dialogue. Thereafter, we used both names as meaning the same organization. The Global Community means the Earth Community Organization and vice versa. The idea of organizing an international conference and calling it a Global Dialogue first originated in 1990 and was thought out by the Global Community also making its first beginning. From that year on, Global Community WebNet Ltd. has operated its business under the name of the Global Community and is still doing now. The business owns copyrights on all materials produced during every Global Dialogue since 1990.

All Participants of Global Dialogue 2000, the World Congress on Managing and Measuring Sustainable Development - Global Community Action 1 have been given a lifetime membership of the Global Community organization.

This is the founding group of the Global Community organization, Earth Community Organization, Global Community Earth Government, the Global Dialogue concept, and the global community concepts and universal values. Along with the new Participants to Global Dialogue 2005, this is also the founding group of this Global Constitution. The list of all Founding Members was shown in Chapter XXVII.

4. Throughout this Global Constitution, the expressions 'Earth Government', 'Global Community Earth Government' and 'GCEG' were used to mean the same organization. These expressions represent the same entity and legal personality and, therefore, were used interchangeably.

Article 2: Earth Government's values

Earth Government is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, liberty, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human and Earth rights. These values are common to Member Nations in a society of pluralism, tolerance, justice, solidarity and non-discrimination. These values along with the "Beliefs, Values, Principles and Aspirations" of Earth Government, are meant to give global citizens a sense of direction.

Article 3: Earth Government's objectives

1. Earth Government's aim is to:

1.1 promote peace, its values and the well-being of its Peoples;

1.2 protect the global life-support systems by:

* good governance and management

* governing keeping in mind:

a) the Scale of Human and Earth Rights;

b) the Statement of Rights, Responsibilities and Accountabilities of a person and of the Global Community;

c) the criteria to obtain the Global Community citizenship; and

d) primordial human and Earth rights of Global Community citizens;

2. Earth Government shall offer its Global Community citizens freedom, security and justice without internal frontiers, and a single market for trade where competition is free and undistorted.

3. Earth Government shall work for the global sustainability of all Nations based on balanced economic growth, a social market economy, highly competitive and aiming at full employment and social progress, and with a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment. It shall promote scientific and technological advance. It shall combat social exclusion and discrimination, and shall promote social justice and protection, equality between women and men, solidarity between generations and protection of children's rights. It shall promote economic, social and territorial cohesion, and solidarity among Member Nations. Earth Government shall respect its rich cultural and linguistic diversity, and shall ensure that global s cultural heritage is safeguarded and enhanced.

4. In its relations with the Global Community, Earth Government shall uphold and promote its values and interests. It shall contribute to peace, security, the sustainability of the Global Community, solidarity and mutual respect among Peoples, free and fair trade, eradication of poverty and protection of human rights and in particular children's rights, as well as to strict observance and development of global law of this Global Constitution.

5. These objectives shall be pursued by appropriate means, depending on the extent to which the relevant competences are attributed to the Earth Government in this Global Constitution.

Article 4: Fundamental freedoms and non-discrimination

1. Free movement of persons, goods, services and capital, and freedom of establishment shall be guaranteed within and by Earth Government, in accordance with the provisions of this Global Constitution.

2. In the field of application of the Constitution, and without prejudice to any of its specific provisions, any discrimination on grounds of nationality shall be prohibited.

Article 5: Symbiotical relationships between Earth Government and Member Nations

1. Earth Government shall respect the national identities of Member Nations, inherent in their fundamental structures, political and constitutional, inclusive of regional and local self-government. It shall respect their essential Nation functions, including those for ensuring the territorial integrity of the Nation, and for maintaining law and order and safeguarding internal security.

2. Following the principle of loyal cooperation, Earth Government and Member Nations shall, in full mutual respect, assist each other in carrying out tasks which flow from this Global Constitution. Member Nations shall facilitate the achievement of Earth Government's tasks and refrain from any measure which could jeopardise the attainment of the objectives set out in this Constitution.

3. Earth Government shall seek to establish symbiotical relationships with Member Nations.

Article 6: Legal personality of Earth Government, Global Community Earth Government, GCEG

Earth Government, Global Community Earth Government, and GCEG shall have legal personality. These expressions represent the same entity and legal personality and, therefore, were used interchangeably. They are being expressed throughout this Constitution, and by the Global Community.

Back to top of page

Chapter IV Global Community concepts and universal values

Chapter 4.1 The Glass Bubble concepts of "a Global Community" and "the Global Community"

Article 1: The Glass Bubble concepts

The Glass Bubble concept was designed to illustrate the concepts of 'a global community' and "the Global Community". It is an imaginary space enclosed in a glass bubble. Inside this is everything a person can see: above to the clouds, below into the waters of a lake or in the earth, to the horizons in front, in back, and on the sides. Every creature, every plant, every person, every structure that is visible to him(her) is part of this "global community."Look up, look down, to the right, to the left, in front and behind you. Imagine all this space is inside a giant clear glass bubble. This is "a global community."

Wherever you go, you are inside a "global community". Every thing, every living creature there, interacts one upon the other. Influences inter-weave and are responsible for causes and effects. Worlds within worlds orbiting in and out of one another's space, having their being.

Your presence has influence on everything else inside your immediate global community. To interact knowledgeably within one's global community has to be learned. All life forms interact and depend upon other life forms for survival. Ignorance of nature's law causes such damage, and working in harmony with nature produces such good results.

Your presence has influence on everything else inside your immediate global community.Learn to be aware of that and act accordingly, to create good or destroy, to help or to hurt. Your choice.

Now let us explore this Global Community that we have visited and discover why each member is important ~ each bird, each tree, each little animal, each insect, plant and human being ~ and how all work together to create a good place to live.

You walk like a giant in this Global Community. To all the tiny members you are so big, so powerful, even scary…

You can make or break their world. But by knowing their needs, and taking care, you can help your whole Global Community be a good one.

From the experience in your life and local community tell us:

* Why are you important to this "Global Community"?

* Why is it important to you?

* What do you like about it?

* What bothers you about it?

* Anything need to be done?

* What is really good there?

* What is very very important?

* What is not so important?

* What is not good?

* What is needed to keep the good things?

* What could make them even better?

* What could you do to keep the good things good?

* Could they help get rid of bad things?

* What unimportant things need to go?

* How could you help get rid of these things?

to sustain the Global Community, humanity and all life.

Let each child be aware he either grows up to be a person who helps or a person who destroys.

Each child makes his own choice. He creates his own future in this way. He becomes a responsible citizen.This may or may not inspire some sort of creative project of what "could be" to aid this Global Community to remain healthy.

To interact knowledgeably within one's global community has to be taught ~ especially to urban children. It has to be brought to them very clearly all life forms interact and depend upon other life forms for survival. They need to know "reasons why" ignorance of nature's law causes such damage, and why working in harmony with nature produces such good results.

The concept of the Glass Bubble can be extended to include the planet Earth and all the "global communities" contained therein.

Article 2: Definition of the Global Community

the Global Community: order and hope within chaos

- we are now, and we are the future -

The following definition of the Global Community is appropriate:

"The Global Community is defined as being all that exits or occurs at any location at any time between the Ozone layer above and the core of the planet below."

Article 2: The Global Community concept and the Global Governments Federation

The Global Community concept is an important concept and particularly useful in the context of the Global Governments Federation. A community is not about a piece of land you acquired by force or otherwise. One could think of a typical community of a million people that does not have to be bounded by a geographical or political border. It can be a million people living in many different locations all over the world. The Global Community is thus more fluid and dynamic. We need to let go the archaic ways of seeing a community as the street where I live and contained by a border. Many conflicts and wars will be avoided by seeing ourselves as people with a heart, a mind and a Soul, and as part of a community with the same. The Global Community is this great, wide, wonderful world made of all these diverse global communities.

To become a member of the Global Community you can be:

* a person

* a global community

* an institution

* a town, city or province

* a state or a nation

* a business

* an NGO

* a group of people who decided to unite for the better of everyone participating in the relationship

* an international organization

Any of these groups can formed together a global symbiotical relationship.

A global symbiotical relationship between two or more nations, or between two or more global communities, can have trade as the major aspect of the relationship or it can have as many other aspects as agreed by the people involved. The fundamental criteria is that a relationship is created for the good of all groups participating in the relationship and for the good of humanity, all life on Earth. The relationship allows a global equitable and peaceful development.

This is the basic concept that is allowing us to group Member Nations from different parts of the world. For example, the Global Government of North America can be made of willing Member Nations such as Canada, the United States, Mexico, Great britain, Israel, the Territories, and include the North Pole region (Politics and Justice without borders: Global Government of North America).

The old concept of a community being the street where we live in and surrounded by a definite geographical and political boundary has originated during the Roman Empire period. An entire new system of values was then created to make things work for the Roman Empire. Humanity has lived with this concept over two thousand years. Peoples from all over the world are ready to kill anyone challenging their border. They say that this is their land, their property, their 'things'. This archaic concept is endangering humanity and its survival. The Roman Empire has gone but its culture is still affecting us today. Other world government models use the old concept as a basis for development. They are obviously wrong.We need to let go the old way of thinking. We need to learn of the new concept, and how it can make things work in the world. Soon humanity will be populated with 10 billion human beings. We are people, not a piece of land. Earth does not belong to anyone. Land does not belong to anyone. It never did and never will. We can only say we manage the land we live on. The old world government models aim at forcing people to live in a specific (magna) region. That is wrong!

Our young people today share their thoughts and feelings with their 'virtual friends' half way around the globe. No border or 'magna region' is big enough to hold them back. Already they have a sense of what it takes to live in a group, to think alike. The seeds of global co-operation are in healthy grounds. From the poorest of them to the richest is created a unique bound, a symbiotical relationship.

Chapter 4.2 Universal Values

Article 1: Social Universal Values are meant to bring together the billions of people around the world for the good of all humanity

Social Universal Values are meant to bring together the billions of people around the world for the good of all humanity. These values are the common grounds to start a new global dialogue. East and West talking; capitalism and communism, all different political and social philosophies and structures reaching to one another, compromising, changing, letting go old ways that dont work, creating new ways that do, and finding what is very important to ensure a sound future for Earth. All peoples on Earth will now join forces to bring forth a sustainable global society embracing universal values related to human and Earth rights, economic and social justice, respect of nature, peace, responsibility to one another, and the protection and management of the Earth. Everyone shares responsibility for the present and future well-being of life within the Global Community.

The following universal values are now an integral part of Earth Government.

a. Working together to keep our planet healthy, productive and hospitable for all people and living things. This requires quality symbiotical relationships and responsibility to one-self and others, and dealing wisely with consumption, work, finances, health, resources, community living, family, life purpose, wildlife and the Earth.

b. We are committed to be responsible to ourselves and to one another, and to sustaining Earth. The key is personal responsibility and accountability. Therefore the individual is the important element, one who takes responsibility for his/her community. As previously defined, an 'individual' here may either be a person, a corporation, a NGO, a local community, a group of people, organizations, businesses, a nation, or a government.

c. Apply a wellness approach in dealing with physical well-being. There is a multitude of influences shaping family life and its well-being. Wellness is a concept related to physical well-being. It is a new health paradigm replacing the old model of doctors, drugs, and treating symptoms. Spiritual well-being deals with mental, emotional and spiritual as well as physical health. Instead of blaming the doctor for an illness and expecting insurance companies and government to pick up the health care tab, a wellness approach places personal responsibility as part of the solution.

d. All cultures and nations value the family as an important social unit. The family is the basic social unit of the Global Community.

e. The Global Community is becoming pluralistic. Recognition and respect of this pluralism is a necessity for the survival of mankind. The history of humanity has always been that of an increasingly more complex interrelationship between its members. Clans to tribes, to nations, to empires, and to today's economic and political alliances. Societies have become global and communications have made us all 'neighbours'. Massive migrations within and among countries have contributed to increasing contacts between human beings of different origins, religions, ideologies, and moral-value systems.

f. Earth Government recognizes that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. Freedom is both a principle and a value. It is because human beings are free that they are subject of law and are creators and holders of rights. Freedom and human rights are therefore basic to each other. Equality and freedom are therefore accepted and enshrined as universal values by which Earth Government shall govern its affairs. As universal values they are concerned with our ability to decide, to choose values and to participate in the making of laws, and they are dependent on the recognition of other people. These values forbid any form of discrimination on the grounds of race, nationality, sex, religion, age or mother tongue. By accepting both values of freedom and equality we can achieve justice. One can be answerable for one's actions in a 'just' way only if judgements are given in the framework of democratically established laws and courts. Social justice is another universal value to which Earth Government aspires and accepts as a universal value. Social justice consists in sharing wealth with a view to greater equality and the equal recognition of each individual's merits. Human and Earth rights and democracy are closely intertwined. Respect for human and Earth rights and fundamental freedoms is one of the characteristics of a democracy. The typical fundamental freedoms of a democracy (freedom of expression, thought, assembly, and association) are themselves part of human and Earth rights. These freedoms can exist everywhere.

g. An adequate level of health care is a universal value as well as a human right. We expect adequate universal health services to be accessible, affordable, compassionate and socially acceptable. Earth Government is proposing that every individual of a society is co-responsible for helping in implementing and managing health programmes along with the government and the public institutions.

h. There are universal quality of life values which lead to "human betterment" or the improvement of the human condition. In addition to the value of species survival (human and other living organisms), they include: adequate resources, justice and equality, freedom, and peace or balance of power. A better quality of life for all people of the Global Community is a goal for all of us and one of our universal values.

i. For a community to be sustainable there has to be a general social and economical well-being throughout the community. Health is the basic building block of this well-being. Health is a complex state involving mental, emotional, physical, spiritual, social and economical well-being. Health promotion generates living and working conditions that are safe, stimulating, satisfying and enjoyable. To reach a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, a community must be able to identify and to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change with the environment. The overall guiding principle for the community is the need to encourage reciprocal maintenance, to take care of each other and the environment. The important part of the thinking in both community health and ecological sustainability is the need to find a sense of community as a crucial aspect of a healthy individual development.

j. The Global Constitution is a declaration by every human being to the commitment of responsibility to themselves and to one another, and to sustaining Earth. The key is participation in the sustainable development process, personal responsibility and accountability. Therefore the individual is the important element, one who takes responsibility for his/her community. As previously defined, an 'individual' here may either be a person, a corporation, a NGO, a local community, a group of people, organizations, businesses, a nation, or a government. We are all working together to keep our planet healthy, productive and hospitable for all people and living things. This requires quality symbiotical relationships and responsibility to one-self and others, and dealing wisely with consumption, work, finances, health, resources, community living, family, life purpose, wildlife and the Earth. We are also all accountable to others about our actions and the things we do throughout our lives.

k. The Global Constitution is an acceptance and commitment about peace, freedom, social and economic well-being, ecological protection, global ethics and spiritual values; it also recognizes the interactions between aspects included in the major quality systems such as: economic, environmental, social, and the availability of resources.

l. Responsibility and accountability are universal values. Every individual on Earth is responsible and accountable for their action(s).

Chapter 4.3 Global Ethics

Article 1: Global ethics must always be grounded in realities.

1. As a business you may:

a) be a corporate Knight

b) be a socially responsible investor

c) have taken the challenge of a more integrated approach to corporate responsibility by placing environmental and community-based objectives and measures onto the decision-making table alongside with the strategic business planning and operational factors that impact your bottom-line results

d) provide not only competitive return to your shareholders but you also operate your business in light of environmental and social contributions, and you have understood the interdependence between financial performance, environmental performance and commitment to the community

e) have taken a full life-cycle approach to integrate and balance environmental and economic decisions for major projects

f) have an active Environmental, Health and Safety Committee and integrated codes of conduct, policies, standards and operating procedures to reflect your corporate responsibility management

g) have scored high on categories such as:

* environmental performanceh) support a balance and responsible approach that promotes action on the issue of climate change as well as all other issues related to the global life-support systems:

* product safety

* business practices

* help small business in the least developed countries

* commitment to the community

* abolition of child labour

* eliminate discrimination in respect of employment and occupation

* employee relations and diversity

* effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining

* corporate governance

* share performance

* global corporate responsibility

* against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery

* health, safety and security

* provided help to combat diseases such as AIDS

* uphold the freedom of association

* audits and inspections

* emergency preparedness

* corporate global ethical values

* ensured decent working conditions

* implemented no-bribe policies

* standards of honesty, integrity and ethical behaviour

* elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour

* in line with the Scale of Human and Earth Rights and the Charter of Global Community

* global warming

* Ozone layer

* wastes of all kind including nuclear and release of radiation

* climate change

* species of the fauna and flora becoming extinct

* losses of forest cover and of biological diversity

* the capacity for photosynthesis

* the water cycle

* food production systems

* genetic resources

* chemicals produced for human use and not found in nature and, eventually, reaching the environment with impacts on Earth's waters, soils, air, and ecology

Now is time to reach a higher level of protection to life on Earth. We all need this for the survival of our species. We can help you integrate and balance global life-support systems protection, global community participation, and economic decisions into your operations and products. We want to help you be an active corporate member of the Global Community. Apply to us to be a global corporate citizen of the Global Community. A Certified Corporate Global Community Citizenship is a unique way to show the world that your ways of doing business are best for the Global Community.

You can obtain the citizenship after accepting the Criteria of the Global Community Citizenship and following an assessment of your business. The process shown here is now standardized to all applicants. You are then asked to operate your business as per the values of the citizenship.

The Global Community proposes to corporations that they take responsibility on behalf of society and people, and that they should pay more attention to human and Earth rights, working conditions and getting ride of corruption in the world of business and trade. We have developed a criteria, and we ask you to turn it into practice. Governments should encourage enterprises to use the criteria both by legal and moral means. At first, the criteria should be adopted in key areas such as procurement, facilities management, investment management, and human resources. Corporations want to be seen as good corporate leaders and have a stronger form of accountability. Business and trade will prosper after stronger common bonds and values have been established. Adopting the criteria will have a beneficial impact on future returns, and share price performance. Sign-up to obtain your Certified Corporate Global Community Citizenship (CCGCC) to show the world your ways of doing business are best for the Global Community. Obtaining the CCGCC shall help businesses to be part of the solution to the challenges of globalisation. In this way, the private sector in partnership with the civil society can help realize a vision: allowing a global equitable and peaceful development and a more stable and inclusive global economy.

2. Earth Government found a way of dealing with globalization: global ethics. In the past, corporations ruled without checks and balances. Now, global ethics will be a basic minimum to do business, and there will be checks and balances. Our judgement will be based on global ethics. Global ethics must always be grounded in realities. But realities are changing constantly and are different in different places. We live in a world that makes progress toward democracy. Ethics and morality exist only when human beings can act freely. In our free society, rights are tied to responsibilities. Corporations are committed to improvement in business performance and want to be seen as 'good corporate citizens' on a local and a global scale. Corporations have social responsibilities as they are an integral part of society. Global ethics recalls that those realities, on which others build upon, have to be protected first. Earth Government has found that universal values and human rights as described above were the foundation of global ethics.

3. The Global Community has now at hand the method and framework to conduct societal checks and balances of a global sustainable development. A more balance world economy will result of annual checks and balances. Corporations will take their social responsibilities and become involved in designing, monitoring, and implementing these checks and balances. Several corporations have already done so. Results will be taken into account in the evaluation of sustainable development. Corporations are required to expand their responsibilities to include human rights, the environment, community and family aspects, safe working conditions, fair wages and sustainable consumption aspects.

Glass Bubble concept of a global community

Every Global Community citizen is part of the solution to the challenges of globalisation. In this way, the private sector in partnership with the civil society can help realize a common vision: allowing a global equitable and peaceful development and a more stable and inclusive global economy.

Every Global Community citizen is part of the solution to the challenges of globalisation. In this way, the private sector in partnership with the civil society can help realize a common vision: allowing a global equitable and peaceful development and a more stable and inclusive global economy.

Chapter 4.4 Global Sustainability

Chapter 4.4.1 Definition and graphical representation of global sustainability

Article 1: Definition of sustainable development.

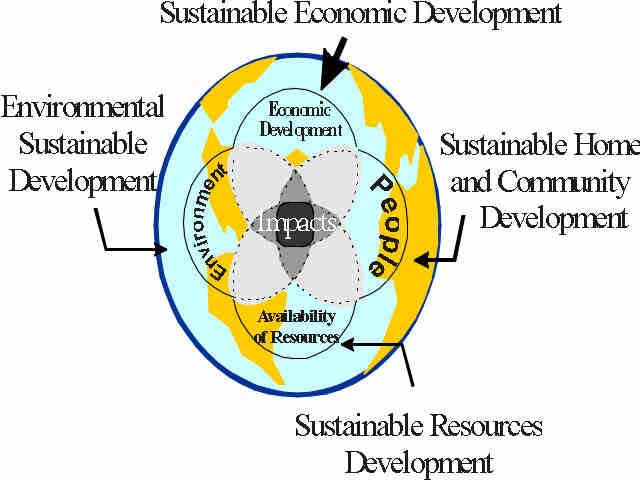

The technical definition being "a sound balance among the interactions of the impacts (positive and/or negative), or stresses, on the four major quality systems: People, Economic Development, Environment and Availability of Resources," and

The none-technical definition being "a sound balance among the interactions designed to create a healthy economic growth, preserve environmental quality, make a wise use of our resources, and enhance social benefits."

When there is a need to find a solution to a problem or a concern, a sound solution would be to choose a measure or conduct an action, if possible, which causes reversible damage as opposed to a measure or an action causing an irreversible loss. Earth Government can help you to realize your actions by coordinating efforts efficiently together.

The following graphics was designed to illustrate the meaning of sustainable development and other global concepts. It is the basis for understanding:

a) the Global Community concepts

b) that Earth is a spiritual Being, a part of the Soul of Humanity

c) interactions between the four major quality systems (small circles, not to scale) shown here

d) that the ecosystem and life-support system of the planet (the large circle around the planet) are much more important for all of humanity and other lifeforms

e) the reason for developing and implementing the Scale of Human and Earth Rights

f) the search of sound solutions and therefore a sound balance amongst interactions

g) the measurement and evaluation of the impact equation

h) the development and use of indicators and indices

i) the reason for creating Earth Government

j) Earth management and good governance

Chapter 4.4.2 Fulfilling the requirements of global sustainability

Article 1: Essential elements of an adequate global sustainability

We will fulfill the requirements for a global sustainable development by using essential elements of an adequate urban and rural development:

a) suitable community facilities and services;

b) decent housing and health care;

c) personal security from crime;

d) educational and cultural opportunities;

e) family stability;

f) efficient and safe transportation;

g) land planning;

h) an atmosphere of social justice;

i) aesthetic satisfaction;

j) responsive government subject to community participation in decision-making;

k) energy conservation and energy efficiency are part of the decision-making process and made part of the community design;

l) the application of the 4 Rs is integrated in the community design;

m) community businesses, working areas, play areas, social and cultural areas, education areas, and training areas;

n) the use of renewable energy sources, central heating where possible, and cogeneration of electricity are made part of the community design when possible;

o) the form of community development integrates concepts such as cooperation, trust, interdependence, stewardship, and mutual responsibility;

p) promote self-sufficiency in all areas such as energy, garbage, food and sewage disposal; and

q) rely on locally-produced goods.

Article 2: Scale of Good Practices

A Scale of Good Practices is developed with respect to the Scale of Human and Earth Rights, and it is developed not only from what it means to fulfill the requirements of a global sustainable development but also from the perspective of keeping us all healthy and sustaining Earth to make it happen. Health is created and lived by people within a global community: where they work, learn, play, and love. Health is a complex state involving mental, emotional, physical, spiritual, economical and social well-being. Each community can develop its own ideas of what a healthy community is by looking at its own situation, and finding its own solutions. Health promotion generates living and working conditions that are safe, stimulating, satisfying and enjoyable. To reach a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, a community must be able to identify and to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change with the environment. The overall guiding principle for the global community is the need to encourage reciprocal maintenance, to take care of each other and the environment. The important part of the thinking in both community health and ecological sustainability is the need to find a sense of global community as a crucial aspect of healthy individual development.

Article 3: Implementing economic activity that can advance sustainability

We will fulfill the requirements for a global sustainable development by implementing economic activity that can advance sustainability by:

a) reducing per capita consumption of energy and resources;Article 4: Implementing various conservation strategies

b) reducing energy and resource content per unit of output;

c) reducing waste discharges per unit of output and in total;

d) decreasing wastage of natural resources during harvesting and processing, thus increasing the amount put to productive use.

We will fulfill the requirements for a global sustainable development by implementing various conservation strategies such as:

a) the maintenance of ecological succession, soil regeneration and protection, the recycling of nutrients and the cleansing of air and water;

b) the preservation of biological diversity, which forms the basis of life on Earth and assures our foods, many medicines and industrial products;

c) the sustainable use of ecosystems and species such as fish, wildlife, forests, agricultural soils and grazing lands so that harvests do not exceed rates of regeneration required to meet future needs;

d) the use of non-renewable resources in a manner that will lead to an economy that is sustainable in the long term. This will require the development of renewable substitutes;

e) the reduction in soil erosion by changing farming practices.

Article 5: Assessing using a combined social and economic accounting system

We will fulfill the requirements for a global sustainable development by developing a combined social and economic accounting system that covers not only the conventional economic indicators (GDP, GNP, etc.) but also such matters as soil depletion, forest degeneration, the costs of restoring a damaged environment and the effects of economic activity on health.

Article 6: Creating tests for sustainability

We will fulfill the requirements for a global sustainable development by creating tests for sustainability:

a) the amount of arable land and forest that is being lost;Article 7: Making forest management to include getting more value out of the wood

b) the amount of silt in rivers coming from eroded farm fields;

c) the loss of large numbers and even whole species of wildlife;

d) the positive and negative impact of process and products on health;

e) the impact of development on the stock of non-renewable resources such as oil, gas, metals and minerals;

f) the impact of waste products;

g) the ability of new proposals to implement cleaner and more resource-efficient techniques and technologies.

We will fulfill the requirements for a global sustainable development by being committed to make forest management to include getting more value out of the wood. This means wasting less of the trees that are cut and making better use of what are now considered non-commercial tree speices.

Article 8: Requiring formal impact assessment for all major projects

We will fulfill the requirements for a global sustainable development by requiring formal Impact Assessment for all major projects so as to predict the sustainability of these developments and determine whether impacts can be mitigated.

Chapter 4.4.3 Developing a scale of values and designing and testing quality indicators

Article 1: Developing a scale of values and designing and testing quality indicators

Developing a scale of values and designing and testing quality indicators is the most important task. The Gross Environmental Sustainable Development Index (GESDI) is quantitatively describing quality indicators rather than merely measuring different variables. GESDI includes all possible aspects, all physical, biological, health, social and cultural components which routinely influences the lives of individuals and communities. If we are to achieve effective evaluation of quality, comprehensive data are needed about the status and changes of the variables. Optimally, these data may be organized in terms of indices that in some fashion aggregate relevant data. These indices are in turn used to predict the impact of public and private actions, assess conditions and trends, and determine the effectiveness of programs in all areas. For instance, reliable data are needed to evaluate the effects of human activities on the environment and to determine what possible actions that can be done to ameliorate the adverse effects. The quality of urban environment constitutes a major test of the level of the well-being of a nation as a society. Essential elements of an adequate urban environment include the following parts:

* Health care system, * Educational system, * Seniors'care, * Food chain, nutrition, * Population growth, * Farming communities, * Parks, * Psychological, biological, genetics and evolution, * Spiritual pathways, * Entertainment, * Quality of life, customs and beliefs, information access, communication, aesthetics * Decent housing, suitable community services, * Pollution, waste, * An atmosphere of social justice, * Family stability, * Religion, * Infrastructures and facilities, land planning, * Juvenile crimes, gangs, drugs, illiteracy, * Socio-cultural and political influences, multi-culturalism, laws, * Anthropological, Aboriginals, Natives issues.

Knowing what are the important elements of a global sustainable development allows us to structure indicators into major areas such as demographic data; the economic data of the individual, family, and household; the status of the region's economy; housing, community facilities, and aesthetic quality; social quality.

An other indicator was developed to measure the costs of development: the Gross Sustainable Development Product (GSDP). The GSDP is defined as the total value of production within a region over a specified period of time. It is measured using market prices for goods and services transactions in the economy. The GSDP is designed to replace the Gross Development Product (GDP) as the primary indicator of the economic performance of a nation.

The GSDP takes into accounts:

a) the economic impacts of environmental and health degradation or improvement, resource depletion or findings of new stocks, and depreciation or appreciation of stocks;

b) the impact of people activity on the environment, the availability of resources, and economic development;

c) the "quality" of the four major quality systems and the impacts of changes in these systems on national income and wealth;

d) global concerns and their impacts on the economy;

e) the welfare, economic development and quality of life of future generations;

f) expenditures on pollution abatement and clean-ups, people health, floods, vehicle accidents, and on any negative impact costs;

g) the status of each resource and the stocks and productive capacities of exploited populations and ecosystems, and make sure that those capacities are sustained and replenished after use; and

h) the depreciation or appreciation of natural assets, the depletion and degradation of natural resources and the environment, ecological processes and biological diversity, the costs of rectifying unmitigated environmental damage, the values of natural resources, capital stocks, the impacts of degradation or improvement, social costs, health costs, environmental clean-up costs, and the costs of the environment, economic growth, and resources uses to current and future generations and to a nation’s income.

Chapter 4.4.4 The Global Community Overall Picture

Article 1: The Global Community Overall Picture

Within each Global Ministry there is a section about the 'Global Community Overall Picture' which describes the situation in all nations of the world and we divided the world in different regions: North America, Central America and the Caribbean, South America, Africa, Europe, Asia, South-East Asia, Middle-East, and Oceania. Each global ministry has a description of what is happening in the different regions. There are actual facts about what is happening in the world about all issues we have discussed during global dialogues in years 2000, 2002, 2004, and 2005. Issues of future global dialogues are also included in this project. Our work is too create a plausible scenario(s) of what the world is now and what it could be between now and a not-so-distant future. Hundreds of indicators were designed to assess the world situation in all aspects. Some of the very important aspects were listed here. The measurements of the GESDI and the GSDP take into account all aspects.

Land and nationsArticle 2: Measurement of the Gross Sustainable Development Product (GSDP)

Water and nations

Clean air and nations

Food supplies

Our overpopulated planet

Status of primordial human rights

Status of community and social rights

Status of cultural rights

Status of religious rights

Status of civil and political rights

Status of business and consumer rights

The measurement of GSDP shows that consumption levels can be maintained without depleting and depreciating the quality and quantity of services. It indicates the solutions to the problems as well as the directions to take, such as:

a) invest in technology, R & D, to increase the end-use efficiency;The measurement of GSDP also gives a proper and sound signal to the public, government and industry about the rate and direction of economic growth; it identifies environmental, health, and social quality; it identifies sustainable and unsustainable levels of resource and environmental uses; it measures the success or failure of sustainable development policies and practices; and it identifies resource scarcity. Values obtained enable us to make meaningful comparisons of sustainable development between cities, provinces, nations over the entire planet.

b) increase productivity;

c) modify social, educational programs and services;

d) slow down or increase economic growth;

e) remediate components of the four major quality systems; and

f) rectify present shortcomings of income and wealth accounts.

A status report of all physical accounts show the physical state and availability of resources and the state of the environment. Examples of the physical stock accounts are:

• minerals • oil, gas and coal • forests • wildlife • agricultural • soils • fish • protected wilderness areas • flow rate of water

Article 3: Valuation in terms of money accounts for some non-market values

Valuation in terms of money accounts is difficult for some non-market values such as:

* aesthetic satisfaction * air quality * water quality * soil carrying capacity and productivity * acid rain deposition * biodiversity * wilderness and protected areas * land productivity

GESDI can be obtained for these quality indicators that are difficult to give a money value to. Both the GESDI and GSDP are measured together and tell us about the quality and cost of development, locally and globally.

Measurements of GESDI and GSDP provide insights for the discussion of issues such as :

a) Is the actual rate of development too slow or too fast?

b) Are People aspects being stressed too far?

c) Are resources and the environment managed in a sustainable manner?

d) What forms of community and home designs promote sustainability?

e) In what ways should social, educational, and health programs and services be modified?

f) Is this generation leaving to the future generation a world that is at least as diverse and productive as the one it inherited?

g) What improvements can be brought up to the quality of development?

Back to top of page

Chapter V The establishment of Global Communities

Article 1: PrinciplesArticle 4: Formation of global communities

The Global Community and its membership, in pursuit of the Purposes stated earlier in the Preamble, shall conduct actions in accordance with the following Principles:

1. The Global Community shall establish local communities of one million people each for a total of about 7,000 elected representatives throughout the world; the number of representatives will change according to the change in Earth's population; the election of representatives shall follow a democratic process properly supervised;Article 2: Birth right of Global Community citizens of electing representatives democratically

2. The Global Community is based on the principle of the equality of all its elected, nominated or appointed representatives;

3. All Members shall fulfill in good faith the obligations assumed by them in accordance with the present Constitution;

4. International disputes shall be resolved peacefully with no threat to international peace, security and justice;

5. International relations shall refrain from using threat or force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any national government;

6. The Global Community shall not intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any national government;

7. The use of armed forces against any national government is prohibited. When there is a need to find a solution to a problem or a concern, a sound solution would be to choose a measure or conduct an action, if possible, which causes reversible damage as opposed to a measure or an action causing an irreversible loss. This Principle applies to all disputes and conflicts.

8. The Scale of Human and Earth Rights shall be used as guiding light for the decision-making process; and

9. The Statement of Rights, Rersponsibilities and Accountabilities of a Person and of the Global Community shall also be used as a guiding light for the decision-making process.

Everyone is part of the Global Community by birth and therefore everyone has a right to vote. It is our birth right of electing a democratic government to manage Earth: the rights to vote and elect our representatives. Everyone should be given a chance to vote. Decisions will be made democratically.

Article 3: Complying with the "Belief, Values, Principles and Aspirations of the Global Community and Earth Government".

Every member shall uphold the Global Constitution and comply with these "Belief, Values, Principles and Aspirations of the Global Community and Earth Government". The Preamble and Chapters 1 to 10 of this Constitution describe these "Belief, Values, Principles and Aspirations of the Global Community and Earth Government"

1. Membership in the Global Community is open to any person (group, NGO, state, businesses, city, Member Nation, or any global citizen) which accept the obligations contained in the present Constitution and are able and willing to carry out these obligations.

2. The admission of any such global community to membership in the Global Community will be effected by a decision of the Earth Executive Council.

Article 5: Portal of the Global Community

Portal of the Global Community

Earth Governance and Management

Global Sustainability

The information gateway empowering the movement for the protection of the

global life-support systems

Portal of the Global Community of North America

The original and best Global Community portal - with search engine, links to sites and news, press releases, letters, reports, action alert, educational and training programs, scientific evaluations, business assesments and support, workshops and global dialogues and more!

Article 6: Portal of the Global Community of North America

[ Global Government of North America ] [ Global Governments Federation ] [ Global Community Earth Government ] [ Activities of the Global Community ] [ Portal of the Global Community ] [ Global Constitution ] [ Global Exhibition ] [ People participation ] [ Citizenship ] This is the Portal for all Citizens of the North American Community. Let us build up our Community. Get involve with issues. Promote a program or a project. Tell us what you think. Tell us what you want.

Article 7: Portal of other global communities

We invite all Nations of the world to participate in the development of global communities everywhere.Back to top of page

Chapter VI Earth Government Global Community Citizenship

Chapter 6.1 Criteria for becoming Global Community citizens

Article 1: Global Community citizenship of Earth Government

1. Every national of a Member Nation shall be a global citizen of Earth Government. Global Community citizenship of Earth Government shall be additional to national citizenship; it shall not replace it.

2. Global Community citizens of Earth Government shall enjoy the rights and be subject to the duties provided for in this Global Constitution. They shall have:a) the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member Nations;3. These rights shall be exercised in accordance with the conditions and limits defined by this Constitution and by the measures adopted to give it effect.

b) the right to vote and to stand as candidates in elections to the Global Parliament and in municipal elections in their Member Nation of residence, under the same conditions as nationals of that Nation; and

c) the right to enjoy, in the territory of a third country in which Member Nation of which they are nationals is not represented, the protection of the diplomatic and consular authorities of any Member Nation on the same conditions as the nationals of that Nation;

d) the right to petition Global Parliament , to apply to the global Ombudspersons, and to address the Institutions and Advisory Bodies of Earth Government in any of the Constitution's languages and to obtain a reply in the same language.

Article 2: Global Community Citizenship

All peoples on Earth have been wondering what will it take to create and obtain a global community citizenship that is based on fundamental principles and values of the Global Community. Now is time to enact your dream! It is time because humanity has no time to waste as we have done in the past. It is time to be what we are meant to become to save us and all life along with us. It is time to be citizens of the Earth. It is time to gather our forces and to stand for our global values, the only humane values that can save humanity and life on the planet from extinction.

Article 3: Who can have a Global Community Citizenship?

You may be eligible to become a citizen of the Global Community. To become a citizen of the Global Community you may be a person and a person may be:

* a global community,The Global Community Citizenship is given to anyone who accepts the Criteria of the Global Community Citizenship as a way of life. It is time now to take the oath of global community citizenship. We all belong to this greater whole, the Earth, the only known place in the universe we can call our home.

* an institution,

* a town, city or province,

* a national government,

* a business,

* an NGO,

* a group of people who decided to unite for the better of everyone participating in the relationship,

* an international organization, or

* a Member Nation.

Chapter 6.2 Criteria of the Global Community Citizenship

Article 1: Criteria of the Global Community Citizenship

To obtain the Global Community Citizenship, you are required to comply with the "Belief, Values, Principles and Aspirations of the Global Community and Earth Government" as described in the Preamble and in Chapters 1 to 7 inclusive of this Constitution. Before you make your decision, we are asking you to read very carefully the Criteria of the Global Community Citizenship, make sure you understand every part of the criteria, and then make the oath of belonging to the Global Community, the human family, Earth Community and Earth Government. You do not need to let go the citizenship you already have. No! You can still be a citizen of any nation on Earth. The nation you belong to can be called 'a global community'. But you are a better human being as you belong also to the Global Community, and you have now higher values to live a life, to sustain yourself and all life on the planet. You have become a person with a heart, a mind and Soul of the same as that of the Global Community.

1. Acceptance of the Statement of Rights, Responsibilities and Accountabilities of a Person, 'a Global Community' and 'the Global Community'.

We need to take this stand for the survival of our species.

2. Acceptance of the concept of 'a global community'.

The concept of 'a global community' is part of the Glass Bubble concept of a global community. The concept was first researched and developed by the Global Community.

3. Acceptance of the Scale of Human and Earth Rights.

To determine rights requires an understanding of needs and reponsibilities and their importance. The Scale of Human and Earth Rights and the Global Constitution were researched and developed by the Global Community to guide us in continuing this process. The Scale shows social values in order of importance and so will help us understand the rights and responsibilities of global communities.

4. Acceptance of the Global Constitution.

The Global Constitution is a declaration of interdependence and responsibility and an urgent call to build a global symbiotical relationship between nations for sustainable development. It is a commitment to Life and its evolution to bring humanity to God. The Global Community has focused people aspirations toward a unique goal: humanity survival now and in the future along with all Life on Earth.

5. Acceptance of your birth right of electing a democratic government to manage Earth.

The political system of an individual country does not have to be a democracy. Political rights of a country belong to that country alone. Democracy is not to be enforced by anyone and to anyone or to any global community. Every global community can and should choose the political system of their choice with the understanding of the importance of such a right on the Scale of Human and Earth Rights. On the other hand, representatives to Earth Government must be elected democratically in every part of the world. An individual country may have any political system at home but the government of that country will have to ensure (and allow verification by Earth Government) that representatives to Earth Government have been elected democratically. This way, every person in the world can claim the birth right of electing a democratic government to manage Earth: the rights to vote and elect representatives to form Earth Government.

6. Acceptance of the Earth Court of Justice as the highest Court on Earth.

The Global Community is promoting the settling of disputes between nations through the process of the Earth Court of Justice. Justice withour borders! The Earth Court of Justice will hear cases involving crimes related to the global ministries. It will have the power to rule on cases involving crimes related to each one of the ministries.

6. Statement of rights, responsibilities, and accountabilities of the Global Community citizens

Chapter 6.3 Statement of rights, responsibilities and accountabilities of Global Community citizens

(see webpage http://globalcommunitywebnet.com/global06/statement.htm for more info on Statement)

Chapter 6.3.1 Statement

Article 1: Statement of Rights, Responsibilities and Accountabilities of a Person, 'a Global Community' and 'the Global Community'

Ever since the early 1990s, the Global Community has researched and developed the concept of 'a global community'. It has since been made a part of the foundation of the Global Community and is thought as the way of life of the future. The concept is also in the statement of rights, responsibilities and accountabilities of a person belonging to 'a global community' and to 'the Global Community', the human family.

That is, the statement is about to take a stand:

a) I am not just a woman, I am a person, I am citizen of a global community,We need to take this stand for the survival of our species.

b) I am not just a man, I am a person, I am citizen of a global community,

c) We are responsible, accountable and equal persons in every way, and we will manage wisely our population and Earth, and

d) We are citizens of the Global Community, the Earth Community, the human family.

Article 2: The Statement includes rights, responsibilities and accountabilities

A) Rights, responsibilities and accountabilities of a person in ' a global community '

B) Rights, responsibilities and accountabilities of a person in ' the Global Community '

C) Rights, responsibilities and accountabilities of ' a global community '

D) Rights, responsibilities and accountabilities of ' the Global Community '

The Statement of Rights, Responsibilities and Accountabilities of a Person, 'a Global Community' and 'the Global Community', the human family, was not, at first, meant to replace the Universal Declaration of Human and Earth Rights developed by the Global Community. But the Declaration becomes redundant. Only the statement was necessary. Even the Universal Declaration of Human Rights becomes redundant here. The introduction of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has been a great step in humanity's evolution to better itself. But now is time to leave it behind and reach to our next step, that is a social scale of values, the Scale of Human and Earth Rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights causes confusion in the world between nations. The reason why it causes confusion is that it needs to be improved. A lot! The West cannot understand many of the things that other nations do and other nations do not understand the West Way of Life. Why? Because the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is not so universal after all. And because it does not have a scale of social values.Certainly a more concise description of the rights, responsibilities and accountabilities of a person and of 'a global community' and that of 'the Global Community' is required at this time. Each person of 'the Global Community' is important, and we all work together to create a good place to live. Now is time to assign rights, responsibilities and accountabilities to global communities. What rights, responsibilities and accountabilities should be assigned to 'a global community' and to the Global Community? What rights, responsibilities and accountabilities to assign to a person in global communities?

The statement of rights of a person and of the Global Community can be integrated into our lives by taking a stand on values. The Global Community is asking all nations to adopt and entrench this statement into your way of life and State Constitution. Make it acceptable to your society. Educate children of it.

It is understood that whenever a person is given a right or a responsibility then 'a global community' and 'the Global Community' give the right or responsiblity to that person. Similarly, whenever a right or a responsibility is given to 'a global community' or to 'the Global Community' then the rights, responsibilities and accountabilities of a person are readjusted accordingly.

Chapter 6.3.2 Rights, responsibilities and accountabilities

Article 1: Proper governance of Earth

Proper governance of Earth is the most importance function of the Global Community and Earth Government. We define Earth governance as the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised for the common good. This includes:

(i) the process by which those in authority are selected, monitored and replaced,

(ii) the capacity of the government to effectively manage its resources and implement sound policies with respect to the Scale of Human and Earth Rights and the belief, values, principles and aspirations of the Global Community,

(iii) the respect of citizens and the state for the institutions that govern economic, environment, Earth resources, and social interactions among them,

(iv) the freedom of global citizens to find new ways for the common good, and

(v) the acceptance of responsibility and accountability for our ways.

Article 2: The quality of Earth governance

The quality of Earth governance is reflected in each local community worldwide. Earth Government shall show leadership by creating a global civil ethic within the Global Community. The Global Constitution describes all values needed for good global governance: mutual respect, tolerance, respect for life, justice for all everywhere, integrity, and caring. The Scale of Human and Earth Rights has become an inner truth and the benchmark of the millennium in how everyone sees all values. The Scale encompasses the right of all people to:

a) the preservation of ethnicity,

b) equitable treatment, including gender equity,

c) security,

d) protection against corruption and the military,

e) earn a fair living, have shelter and provide for their own welfare and that of their family,

f) peace and stability,

g) universal value systems,

h) participation in governance at all levels,

i) access the Earth Court of Justice for redress of gross injustices, and

j) equal access to information

Article 3: The most fundamental community right

The Global Constitution is itself a statement for the fundamental rights of all Global Community citizens, ensuring the rights of minorities, one vote per million people from each state government. When member nations vote during any meeting they are given the right of one vote per million people in their individual country. That is the most fundamental community right, the right of the greatest number of people, 50% plus one, and that is the 'new democracy' of Earth Government.

Article 4: Justice is without borders

Governance of the Earth will make the rule of arbitrary power--economic (WTO, FTA, NAFTA, EU), monetary (IMF, WB) political, or military (NATO)-- subjected to the rule of global law within Earth Government. Justice is for everyone and is everywhere, a universal constant. Justice is without borders.

Article 5: State governments keep their status and privileges

Earth Government has no intention of changing the status and privileges of state governments. In fact, state governments become primary members of the Earth Government. Global governance can only be effective within the framework of a world government or world federalism. There is no such thing as good global governance through the work of a few international organizations such as the WTO, the EU, or NATO. Earth governance does not imply a lost of state sovereignty and territorial integrity. A nation government exists within the framework of an effective Earth Government protecting common global values and humanity heritage. Earth governance gives a new meaning to the notions of territoriality, and non-intervention in a state way of life, and it is about protecting the cultural heritage of a state. Diversity of cultural and ethnic groups is an important aspect of Earth governance.

Article 6: Vision of Earth Government

Earth Government allows people to take control of their own lives. Earth Government was built from a grassroots process with a vision for humanity that is challenging every person on Earth as well as nation governments. Earth Government has a vision of the people working together building a new civilization including a healthy and rewarding future for the next generations. Global cooperation brings people together for a common future for the good of all.

Article 7: Earth governance is a balance

Earth governance is a balance between the rights of states with rights of people, and the interests of nations with the interests of the Global Community, the human family, the global civil society.

Article 8: The rights of states to self-determination in the global context