Global Civilization vision to saving the world.

Whole paper on this theme.

By

Germain Dufour

May 11, 2017

Authors of research papers and articles on global issues for this month

Robert J Barsocchini, Gene Baur, Cindy Baxter, David Bollier, Jesse Bragg, Swathi Chaganty, Lorraine Chow, Marlene Cimons, Lien permanent Countercurrents, Stan Cox, Finian Cunningham, Marianne de Nazareth (2),Pepe Escobar (2), harold-w-becker, John Hawthorne, Adam Hudson, Tim Jackson, Razmig Keucheyan, Dr Arshad M Khan, Michael T Klare (2), Kristen Miller, Ilana Novick, Tim Radford, Oscar Reyes,Paul Craig Roberts, Alexandra Rosenmann, Nauman Sadiq, Tegan Tallullah, Jakob Terwitte, Diane Tuft, Sarah van Gelder, Rene Wadlow, Allen White.

Robert J Barsocchini, Endless Atrocities: The US Role In Creating The North Korean Fortress-State.

Gene Baur, Making This Simple Lifestyle Switch Can Help Change the Whole World for the Better.

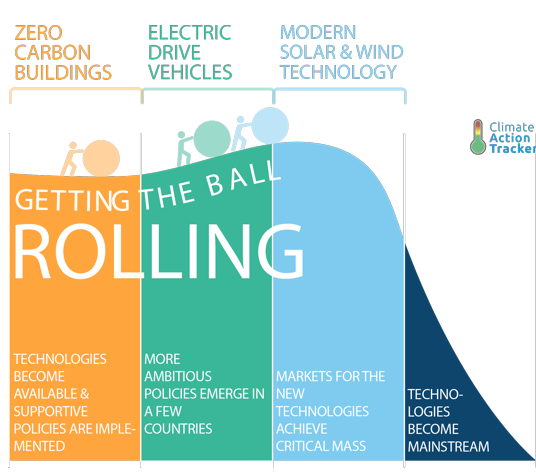

Cindy Baxter, Who Needs Trump? It Takes Only a Few Countries to Kickstart Shift to Low Carbon Energy System.

David Bollier, The Future Is A Pluriverse.

Jesse Bragg, Can Anyone Cook Up a Worse Idea for UN Climate Talks Than Giving the Fossil Industry a Front Seat?

Swathi Chaganty, How Protecting Biodiversity Also Protects the Rich Variety of Foods That We Love to Eat.

Lorraine Chow, How a Supermarket Sales Gimmick Has Become a Major Driver of Climate Change.

Marlene Cimons, Sea-Level Rise Will Send Millions of U.S. Climate Refugees to Inland Cities.

International - Lien permanent , Countercurrents Poubelle nucléaire de Hanford aux Etats-Unis : effondrement d'un tunnel de déchets radioactifs.

Stan Cox, Why the Wealthy Will Have to Make Big Sacrifices to Rein in Climate Change.

Finian Cunningham, The Deep History of US, Britain’s Never-Ending Cold War On Russia.

Marianne de Nazareth, An Expedition to Explore Life on Undersea Mountains.

Marianne de Nazareth, Saving The Amazon Reef.

Pepe Escobar, China Widens its Silk Road to the World

Pepe Escobar, Why Washington is Terrified of Russia, China

harold-w-becker, Beings of Love; Des êtres d'amour; Seres de Amor; Seres de Amor.

John Hawthorne, 7 Crazy Things That Are Going To Happen As Sea Levels Rise.

Adam Hudson, Why Water Privatization Is a Bad Idea for People and the Planet.

Razmig Keucheyan, How Climate Change Leads to Violent Conflict Around the World.

Dr Arshad M Khan, Climate Change Proof To Convince Even The Most Irrational.

Michael T Klare, Climate Change As Genocide.

Michael Klare, Climate Change as Genocide: Inaction Equals Annihilation

Ilana Novick, There Are 21 Million Victims of Human Trafficking Right Now: Coming to Grips and Trying to Solve Mass Human Suffering.

Kristen Miller, Democrats Are Pulling Out All the Stops to Protect the Arctic From Trump.

Tim Radford, A Slice of Greenland's Ice Has Melted Into Oblivion.

Oscar Reyes, Getting Out of Our Coal Hole.

Paul Craig Roberts, Washington is Leading the U.S. and its Vassal States to Total Destruction.

Alexandra Rosenmann, A New Protest Movement Is Rising from the Ashes of Standing Rock, and It's Targeting Big Banks.

Nauman Sadiq, Politics, Not Religion, Is The Source Of Sunni-Shia Conflict.

Tegan Tallullah, 3 Reasons Why Climate Change Is a Human Rights Issue.

Jakob Terwitte, A Revolution of Values.

Diane Tuft, Take a Good Look at the Frozen Beauty of the Arctic Before It All Melts Away.

Sarah van Gelder, The Urban Common Spaces That Show Us We Belong to Something Larger.

Rene Wadlow, Our Common Oceans And Seas.

Allen White, Tim Jackson, To Avoid Ecological Destruction, Prosperity Must Be Separated From Economic Growth

| Day data received | Theme or issue | Read article or paper |

|---|---|---|

| May 15, 2017 |

China Widens its Silk Road to the World

by Pepe Escobar, Information ClearingHouse Beijing hopes its top-level two-day Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, starting this Sunday, will be a game-changer for globalization Let’s cut to the chase. China’s new ‘Silk Road’ initiative is the only large-scale, multilateral development project that the 21st century has seen so far. There is no counter-offer from the West. Which is why the two-day Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, starting this Sunday in Beijing, is being set up as a game-changer for the global economy. Here the initiative looks likely to switch to Mark II mode, accelerating into what President Xi Jinping dubbed, at Davos in January, “inclusive globalization.” The big ideas behind this grand Chinese plan, however, are still getting lost in translation. At first this trans-Asian trade expressway was billed as One Belt, One Road (OBOR), a literal translation from the Chinese yi dai yi lu. Now it’s the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but that still does not really fly in the West, even when China has tried adding a piece of soft power spin, as in its attempts to sell the Belt and Road to English-speaking children:

I have been covering the New Silk Roads since they were first announced in 2013. The idea started at the Commerce Ministry and then developed as a natural extension of the Go West campaign – focused on developing western Xinjiang Province – launched in 1999. The Commerce Ministry now insists OBOR/BRI is a global plan and not just tied to the Xi Jinping presidency. The summit will attempt to portray how its ambitious trade concept has become a multilateral “win-win” shared vision that connects all of Eurasia. Or, to put it more simply, Globalization Mark II. It’s enlightening to examine the pronouncements made by some of China’s top analysts. Wang Huiyao, president of the independent Center for China and Globalization, says this is the “the new engine of globalization.” Shen

Digli, from the Institute of International

Studies at Shanghai’s Wang Yiwei, from the Center of European Studies at Renmin University, is convinced this could be as important as the creation of the European Union. And Shin Yinhong, from the Center of American Studies at Renmin University, points out, crucially, that OBOR/BRI would not work if it were merely a geopolitical gamble. Geopolitics as geo-economics As much as this will act as a boost to economies from Bangladesh to Egypt and Myanmar to Tajikistan, it is also a far-reaching economic/free trade/investment plan that will open up markets for Chinese technology and merchandise. And with this comes priceless geopolitical reach for China. In parallel to this connectivity extravaganza, arguably spanning 65 nations, 60% of the world’s population and a third of global economic output, China will accumulate extra capital from Central Asia to the Middle East. It will also polish its status as leader of the developing world, allowing it to once again try and reignite the 120-nation Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Representatives from more than a hundred nations will converge in Beijing and most of them are from NAM. Of course we will have Vladimir Putin, representing the Russia-China strategic partnership (BRICS, SCO) that spans everything from energy to infrastructure projects (including the future Trans-Siberian high-speed rail). But, crucially, we will also have Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, leaders of two key hubs of OBOR/BRI. Most of the West still needs a weatherman to see which way the wind is blowing. And a lot of Western media revel in dismissing OBOR/BRI as a conspiracy, a “scheme”, or a Chinese attempt to “encircle” Eurasia. Only one G7 leader will be in Beijing; Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni, who is very keen to investigate symbiotic links between Italy’s Industry 4.0 program and China’s Made in China 2025 manufacturing initiative. Angela Merkel might have turned down her invitation but it doesn’t really matter as German industrialists are all for OBOR/BRI. And the Trump administration is starting to wake up to the action following Trump-Xi at Mar-A-Lago. The US delegation will be led by Matt Pottinger, Special Assistant to the President and senior director for East Asia at the National Security Council. And India? The US$62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), one of the highlights of OBOR/BRI, and enthusiastically lauded by Pakistani officials, runs partly through Kashmir. Diplomacy, not trade, would better advance Indian interests. But the reality is the Narendra Modi administration – which has accused China of trying to “undermine the sovereignty of other nations” – is obsessed that the real Chinese agenda is to strategically control the Indian Ocean. So no India in Beijing. Have yuan, will travel The New Silk Road comes with a crossfire of numbers. No one knows for sure the true value of projects already signed along the overland belt and across the Maritime Silk Road, but numbers are said to already be as high as US$300 billion. Most of these projects will be developed well into the next decade. Ratings agency Fitch quotes US$900 billion in projects planned or already happening. Speculation is rife that OBOR/BRI may need as much as US$5 trillion up to 2022. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Asia will need a mind-boggling US$26 trillion for infrastructure projects up to 2030. The Silk Road Fund, set up at the end of 2014, for the moment relies on just US$40 billion – a mix of foreign exchange reserves and input from the China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China. It has invested US$6 billion in 15 projects so far, plus US$2 billion to fund projects in Kazakhstan. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), with 70 member-nations, went online in January 2016 with capital of US$100 billion, but disbursed less than US$2 billion last year. The New Development Bank (NDB), the BRICS bank, is bound to step up soon, after it got a AAA rating from Chinese credit agencies. China has belonged to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) since 2015; that’s the European financing leg for OBOR/BRI. It’s also linked to a fund in Luxembourg and another one in Riga, Latvia. So the key issue for OBOR/BRI remains how to come up with low-cost funding in global capital markets. That will be a top discussion topic at the summit. Zhou Xiaochun, governor of the People’s Bank of China, has already laid down the law; “governments” – including the Chinese government – simply cannot pay for all that’s needed for OBOR/BRI. So everyone will have to rush to capital markets; set up their own OBOR/BRI-related financial mechanisms; and, crucially, do business in local currencies. That is shorthand for using, most of all, China’s currency. So if you are hitting the New Silk Roads, don’t forget your yuan. This article was first published by Asia Times The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Information Clearing House. |

Read |

| 2017 |

Why Washington is Terrified of Russia, China

by Pepe Escobar, Information ClearingHouse

The Russia-China strategic partnership, uniting

the Pentagon's avowed top two "existential"

threats to America, does not come with a formal

treaty signed with pomp, circumstance - and a

military parade.

Enveloped in layers of subtle sophistication, there's no way to know the deeper terms Beijing and Moscow have agreed upon behind those innumerable Putin-Xi Jinping high-level meetings. Diplomats, off the record, occasionally let it slip there may have been a coded message delivered to NATO to the effect that if one of the strategic members is seriously harassed — be it in Ukraine or in the South China Sea – NATO will have to deal with both. For now, let's concentrate on two instances of how the partnership works in practice, and why Washington is clueless on how to deal with it. Exhibit A is the imminent visit to Moscow by the Director of the General Office of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Li Zhanshu, invited by the head of the Presidential Administration in the Kremlin, Anton Vaino. Beijing stressed the talks will revolve around – what else — the Russia-China strategic partnership, "as previously agreed on by the countries' leaders." This happens just after China's First Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli, one of the top seven in the Politburo and one of the drivers of China's economic policies, was received in Moscow by President Putin. They discussed Chinese investments in Russia and the key energy angle of the partnership. But most of all they prepared Putin's next visit to Beijing, which will be particularly momentous, in the cadre of the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) summit on May 14-15, steered by Xi Jinping. The General Office of the CCP – directly subordinated to Xi — only holds this kind of ultra-high-level annual consultations with Moscow, and no other player. Needless to add, Li Zhanshu reports directly to Xi as much as Vaino reports directly to Putin. That is as highly strategic as it gets. That also happens to tie directly to one of the latest episodes featuring The Hollow (Trump) Men, in this case Trump's bumbling/bombastic National Security Advisor Lt. Gen. HR McMaster. In a nutshell, McMaster's spin, jolly regurgitated by US corporate media, is that Trump has developed such a "special chemistry" with Xi after their Tomahawks-with-chocolate cake summit in Mar-a-Lago that Trump has managed to split the Russia-China entente on Syria and isolate Russia in the UN Security Council. It would have taken only a few minutes for McMaster to read the BRICS joint communiqué on Syria for him to learn that the BRICS are behind Russia. No wonder a vastly experienced Indian geopolitical observer felt compelled to note that, "Trump and McMaster look somewhat like two country bumpkins who lost their way in the metropolis." Follow the money Exhibit B centers on Russia and China quietly advancing their agreement to progressively replace the US dollar's reserve status with a gold-backed system. That also involves the key participation of Kazakhstan – very much interested in using gold as currency along OBOR. Kazakhstan could not be more strategically positioned; a key hub of OBOR; a key member of the Eurasia Economic Union (EEU); member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO); and not by accident the smelter of most of Russia's gold. In parallel, Russia and China are advancing their own payment systems. With the yuan now enjoying the status of a global currency, China has been swiftly promoting their payment system, CIPS, careful not to frontally antagonize the internationally accepted SWIFT, controlled by the US. Russia, on the other hand, has stressed the creation of "an alternative," in the words of Russian Central Bank's Elvira Nabiullina, in the form of the Mir payment system — a Russian version of Visa/ MasterCard. What's implied is that were Washington feel inclined to somehow exclude Russia from SWIFT, even temporarily, at least 90 percent of ATMs in Russia would be able to operate on Mir. China's UnionPay cards are already an established fixture all across Asia – enthusiastically adopted by HSBC, among others. Combine "alternative" payment systems with a developing gold-backed system – and "toxic" does not even begin to spell out the reaction of the US Federal Reserve. And it's not just about Russia and China; it's about the BRICS. What First Deputy Governor of Russia's Central Bank Sergey Shvetsov has outlined is just the beginning: "BRICS countries are large economies with large reserves of gold and an impressive volume of production and consumption of this precious metal. In China, the gold trade is conducted in Shanghai, in Russia it is in Moscow. Our idea is to create a link between the two cities in order to increase trade between the two markets." Russia and China already have established systems to do global trade bypassing the US dollar. What Washington did to Iran — cutting their banks off SWIFT – is now unthinkable against Russia and China. So we're already on our way, slowly but surely, towards a BRICS "gold marketplace." A "new financial architecture" is being built. That will imply the eventual inability of the US Fed to export inflation to other nations – especially those included in BRICS, EEU and SCO. The Hollow Men Trump's Generals, led by "Mad Dog" Mattis, may spin all they want about their need to dominate the planet with their sophisticated AirSeaLandSpaceCyber commands. Yet that may be not enough to counter the myriad ways the Russia-China strategic partnership is developing. So more on than off, we will have Hollow Men like Vice-President Mike Pence, with empurpled solemnity, threatening North Korea; “The shield stands guard and the sword stands ready.” Forget this does not even qualify as a lousy line in a cheap remake of a Hollywood B-movie; what we have here is Aspiring Commander-in-Chief Pence warning Russia and China there may be some nuclear nitty-gritty very close to their borders between the US and North Korea. Not gonna happen. So here's to the great T. S. Eliot, who saw it all decades in advance: "We are the hollow men / We are the stuffed men/ Leaning together / Headpiece filled with straw. Alas! / Our dried voices, when / We whisper together / Are quiet and meaningless / As wind in dry grass / Or rats' feet over broken glass / In our dry cellar." The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Information Clearing House. |

Read |

| May 4, 2017 |

The Deep History of US, Britain’s Never-Ending Cold War On Russia

by Finian Cunningham, Information Clearing House

After

decades of delaying, the United Nations finally

released archives from the Second World War-era

war crimes commission investigating the Nazi

Holocaust. The source of those archives on Nazi

war crimes were Western governments, including

those in exile at the time of the war, such as

the Belgian, Polish and Czechoslovakian. The

time period covered is 1943-1949. Washington and

London had long sought to halt the release. Why?

Notably, the landmark publication of the files last month was given scant Western media coverage. Surprisingly, perhaps, because the story that can be gleaned from the documents tells of a hidden history of the Second World War, namely the systematic collusion between the American and British governments and the Nazi Third Reich. As a report in Deutsche Welle remarked on the released archives: «The files make clear that [Western] Allied forces knew more about the Nazi concentration camp system before the end of the war than has generally been thought». This revelation points to more than just «knowledge» among the Western allies of Nazi-era crimes; it points more damningly to state collusion. This would also explain why Washington and London have been reluctant to make the UN war crimes files publicly available. There has long been a controversial debate among Western nations about why the US and Britain in particular did not do more to bomb the Nazi infrastructure of death camps and railroads. Washington and London have often made the claim that they did know the full extent of the horror being perpetrated by the Nazis until the very end of the war when extermination centers such as at Auschwitz and Treblinka were liberated – by the Soviet Red Army, it should be noted too. However, what the latest release of UN Holocaust files shows is that Washington and London were indeed well aware of the Nazi Final Solution in which millions of European Jews and Slavic people were being systematically worked to death or exterminated in gas chambers. So the question again is: why did the US and Britain not direct more of their aerial bombing campaign to destroy the Nazi infrastructure? One possible answer is that these Western allies had a callous disregard for the Nazi victims. Washington and London establishments were themselves accused of harboring antisemitic prejudices, as can be seen from the scandals when both these governments spurned thousands of European Jewish refugees during the Second World War, in effect sending many of them to their deaths under the Nazi regime. Not excluding the above factor of Western racist insouciance, there is a second more disturbing factor. That the Western governments, or at least powerful sections, were loath to hamper the Nazi war effort against the Soviet Union. Notwithstanding that the Soviet Union was a nominal «ally» of the West for the defeat of Nazi Germany. This perspective harks to a radically different conception of the Second World War in contrast to that narrated in official Western versions. In this alternative historical account, the rise of the Nazi Third Reich was deliberately fomented by American and British rulers as a bulwark in Europe against the spread of communism. Adolf Hitler’s rabid anti-Semitism was matched only by his detest of Marxism and the Slavic people of the Soviet Union. In the Nazi ideology, they were all «Untermenschen» (subhumans) to be exterminated in a «Final Solution». So, when Nazi Germany was attacking the Soviet Union and carrying out its Final Solution from June 1941 until late 1944, little wonder then that the US and Britain showed a curious reluctance to commit their military forces fully to open up a Western Front. The Western allies were evidently content to see the Nazi war machine doing what it was originally intended to do: to destroy the primary enemy to Western capitalism as represented by the Soviet Union. This is not to say that all American and British political leaders shared or were even aware of this tacit strategic vision. Leaders like President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill appeared to be genuinely committed to defeating Nazi Germany. Nevertheless, their individual views must be set against a background of systematic collusion between powerful Western corporate interests and Nazi Germany. As American author David Talbot documented in his book, The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA and the Rise of America’s Secret Government (2015), there were massive financial links between Wall Street and the Third Reich, going back several years before the outbreak of the Second World War. Allen Dulles, who worked for the Wall Street law firm Sullivan and Cromwell and who later headed up the American Central Intelligence Agency, was a key player in the linkage between US capital and German industry. American industrial giants, such as Ford, GM, ITT and Du Pont were invested heavily in German industrial counterparts like IG Farben (manufacturer of Zyklon B, the poisonous gas used in the Holocaust), Krupp Steel and Daimler. American capital, as well as British, was thus integrated into the Nazi war machine and the latter’s dependence on the system of slave labor as provided by the Final Solution. This would explain why the Western allies did so little to disrupt the Nazi infrastructure with their undoubted formidable aerial bombing capacity. Far more damning than mere inertia or indifference owing to racist prejudice towards the Nazi victims, what emerges is that the Americans and British capitalist elite were invested in the Third Reich. Mainly for the purpose of eliminating the Soviet Union and any kind of genuinely socialist global movement. Bombing Nazi infrastructure would have been tantamount to deleting Western assets. To this end, as the war was drawing to a close and the Soviet Union looked poised to roll up the Third Reich singlehandedly, the Americans and British belatedly stepped up their war efforts from western and southern Europe. The goal was one of salvaging Western assets remaining in the Nazi regime. Allen Dulles, the director of the-soon-to-be-formed American Central Intelligence Agency, extricated top Nazis and their gold looted from Europe in secret surrender deals known as Operation Sunrise. Britain’s military intelligence MI6 was also involved in the clandestine American effort to salvage Nazi assets via ratlines. The bad faith on display to the Soviet «allies» heralded the chill of the ensuing Cold War that immediately followed the Second World War. Significant and damning testimony of what was going down was given recently in a BBC interview by Ben Ferencz, the most senior surviving US prosecutor from the Nuremberg trials. At age 98, Ferencz was still able to lucidly recall how scores of Nazi war criminals were let off the hook by the American and British authorities. Ferencz cited US General George Patton who remarked just before the final surrender of the Third Reich in early May 1945, as saying: «We’re fighting the wrong enemy». Patton’s candid expression of deeper animosity towards the Soviet Union than towards Nazi Germany was consistent with how the US and British ruling class had been colluding with Hitler’s Third Reich in a geo-strategic war against the Soviet Union and worker-led socialist movements arising across Europe and America. In other words, the Cold War which the US and Britain embarked on after 1945 was but a continuation of hostile policy towards Moscow that was already underway well before the Second World War erupted in 1939 in the form of a build up of Nazi Germany. For various reasons, it became expedient for the Western powers to liquidate the Nazi war machine, along with the Soviet Union. But as can be seen, the Western assets residing in the Nazi machine were recycled into American and British Cold War posture against the Soviet Union. It is a truly damning legacy that American and British military intelligence agencies were consolidated and financed by Nazi crimes. The recent release of UN Holocaust files – in spite of American and British prevarication over many years – add more evidence to the historical analysis that these Western powers were deeply complicit in the monumental crimes of the Nazi Third Reich. They knew about these crimes because they had helped facilitate them. And the complicity stemmed from Western hostility towards Russia as a perceived geopolitical rival. This is not a mere historical academic exercise. Western complicity with Nazi Germany also finds a corollary in the present-day ongoing hostility from Washington, Britain and their NATO allies towards Moscow. The relentless build up of NATO offensive forces around Russia’s borders, the endless Russophobia in Western propagandistic news media, the economic blockade in the form of sanctions based on tenuous claims, are all deeply rooted in history. The West’s Cold War towards Moscow preceded the Second World War, continued after the defeat of Nazi Germany and persists to this day regardless of the fact that the Soviet Union no longer exists. Why? Because Russia is a perceived rival to Anglo-American capitalist hegemony, as is China or any other emerging power that undermines that desired unipolar hegemony. American-British collusion with Nazi Germany finds its modern-day manifestation in NATO collusion with the neo-Nazi regime in Ukraine and jihadist terror groups dispatched in proxy wars against Russian interests in Syria and elsewhere. The players may change over time, but the root pathology is American-British capitalism and its hegemonic addiction. The never-ending Cold War will only end when Anglo-American capitalism is finally defeated and replaced by a genuinely more democratic system. This article was first published by SCF - The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Information Clearing House. |

Read |

| May 6, 2017 |

Washington is Leading the U.S. and its Vassal States to Total Destruction

by Paul Craig Roberts, Information ClearingHouse “The problem is that the world has listened to Americans for far too bloody long.” — Dr. Julian Osborne, from the 2000 film version of Nevil Shute’s 1957 book, On the Beach - A reader asked why neoconservatives push toward nuclear war when there can be no winners. If all die, what is the point?The answer is that the neoconservatives believe that the US can win at minimum and perhaps zero damage. Their insane plan is as follows: Washington will ring Russia and China with anti-ballistic missile bases in order to provide a shield against a retaliatory strike from Russia and China. Moreover, these US anti-ABM bases also can deploy nuclear attack missiles unknown to Russia and China, thus reducing the warning time to five minutes, leaving Washington’s victims little or no time in which to make a decision. The neoconservatives think that Washington’s first strike will so badly damage the Russian and Chinese retaliatory capabilities that both governments will surrender rather than launch a response. The Russian and Chinese leaderships would conclude that their diminished forces leave little chance that many of their ICBMs will be able to get past Washington’s ABM shield, leaving the US largely intact. A feeble retaliation by Russia and China would simply invite a second wave US nuclear attack that would obliterate Russian and Chinese cities, killing millions and leaving both countries in ruins. In short, the American warmongers are betting that the Russian and Chinese leaderships would submit rather than risk total destruction. There is no question that neoconservatives are sufficiently evil to launch a preemptive nuclear attack, but possibly the plan aims to put Russia and China into a situation in which their leaders conclude that the deck is stacked against them and, therefore, they must accept Washington’s hegemony. To feel secure in its hegemony, Washington would have to order Russia and China to disarm. This plan is full of risks. Miscalculations are a feature of war. It is reckless and irresponsible to risk the life of the planet for nothing more than Washington’s hegemony. The neoconservative plan puts Europe, the UK, Japan, S. Korea, and Australia at high risk were Russia and China to retaliate. Washington’s ABM shield cannot protect Europe from Russia’s nuclear cruise missiles or from the Russian Air Force, so Europe would cease to exist. China’s response would hit Japan, S. Korea, and Australia. The Russian hope and that of all sane people is that Washington’s vassals will understand that it is they that are at risk, a risk from which they have nothing to gain and everything to lose, repudiate their vassalage to Washington and remove the US bases. It must be clear to European politicians that they are being dragged into conflict with Russia. This week the NATO commander told the US Congress that he needed funding for a larger military presence in Europe in order to counter “a resurgent Russia.” Let us examine what is meant by “a resurgent Russia.” It means a Russia that is strong and confident enough to defend its interests and those of its allies. In other words, Russia was able to block Obama’s planned invasion of Syria and bombing of Iran and to enable the Syrian armed forces to defeat the ISIS force sent by Obama and Hillary to overthrow Assad. Russia is “resurgent” because Russia is able to block US unilateral actions against some other countries. This capability flies in the face of the neoconservative Wolfowitz doctrine, which says that the principal goal of US foreign policy is to prevent the rise of any country that can serve as a check on Washington’s unilateral action. While the neocons were absorbed in their “cakewalk” wars that have now lasted 16 years, Russia and China emerged as checks on the unilateralism that Washington had enjoyed since the collapse of the Soviet Union. What Washington is trying to do is to recapture its ability to act worldwide without any constraint from any other country. This requires Russia and China to stand down. Are Russia and China going to stand down? It is possible, but I would not bet the life of the planet on it. Both governments have a moral conscience that is totally missing in Washington. Neither government is intimidated by the Western propaganda. Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov said yesterday that we hear endless hysterical charges against Russia, but the charges are always vacant of any evidence. Conceivably, Russia and China could sacrifice their sovereignty for the sake of life on earth. But this same moral conscience will propel them to oppose the evil that is Washington in order not to succumb to evil themselves. Therefore, I think that the evil that rules in Washington is leading the United States and its vassal states to total destruction. Having convinced the Russian and Chinese leaderships that Washington intends to nuke their countries in a surprise attack (see, for example, ), the question is how do Russia and China respond? Do they sit there and await an attack, or do they preempt Washington’s attack with an attack of their own? What would you do? Would you preserve your life by submitting to evil, or would you destroy the evil? Writing truthfully results in my name being put on lists (financed by who?) as a “Russian dupe/agent.” Actually, I am an agent of all people who disapprove of Washington’s willingness to use nuclear war in order to establish Washington’s hegemony over the world, but let us understand what it means to be a “Russian agent.” It means to respect international law, which Washington does not. It means to respect life, which Washington does not. It means to respect the national interests of other countries, which Washington does not. It means to respond to provocations with diplomacy and requests for cooperation, which Washington does not. But Russia does. Clearly, a “Russian agent” is a moral person who wants to preserve life and the national identity and dignity of other peoples. It is Washington that wants to snuff out human morality and become the master of the planet. As I have previously written, Washington without any question is Sauron. The only important question is whether there is sufficient good left in the world to resist and overcome Washington’s evil. Dr. Paul Craig Roberts was Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Economic Policy and associate editor of the Wall Street Journal. He was columnist for Business Week, Scripps Howard News Service, and Creators Syndicate. He has had many university appointments. His internet columns have attracted a worldwide following. Roberts' latest books are The Failure of Laissez Faire Capitalism and Economic Dissolution of the West How America Was Lost and The Neoconservative Threat to World Order. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Information Clearing House.

See also

500K People Sign Petition Barring Trump’s Nuclear Weapons Use: According to the bill, the President will be prohibited from using the Armed Forces to conduct a "first-use nuclear strike" until a congressional declaration of war expressly authorized such a strike. |

Read |

| April 21, 2017 |

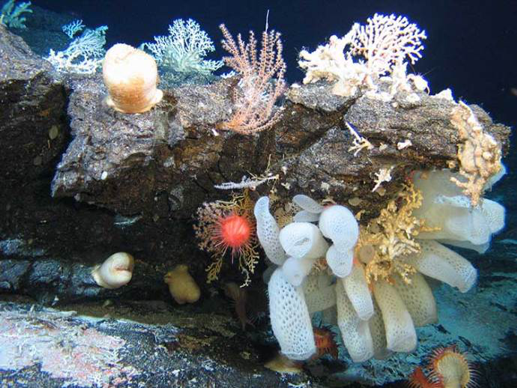

An Expedition to Explore Life on Undersea Mountains

by Marianne de Nazareth, in Environmental Protection, Countercurrents.org  On hard substrata, frequently observed epilithic organisms include corals, actiniarians, hydroids, sponges, ascidians and crinoids – from 2011 seamounts expedition in the SW Indian O_C_IUCN [fwdslash] NERCFor the common man, mountains are a large landform that stretches above the surrounding land in a limited area, usually in the form of a peak. In geography we were taught that a mountain is generally steeper than a hill. And that mountains are formed with movement between tectonic plates or volcanoes erupting. So it is amazing to know that their are mountains under the sea as well and that marine scientists today with the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature ) are undertaking their third expedition to explore these seamounts. This scientific expedition is to explore life on undersea mountains – or seamounts – in the high seas south of Madagascar So why is an expedition like this needed at all one might ask? This expedition is a key stage of a project, aimed at the conservation and sustainable use of seamount ecosystems in the South West Indian Ocean, led by the IUCN. It is a three-week-long expedition aboard the French Polar Institute’s research vessel Marion Dufresne which will explore the fauna of the Walters Shoal seamount. The IUCN explains that while past expeditions concentrated solely on collating information on species inhabiting the seabed and the water, this one will gather extensive data on everything from plankton to seabirds and marine mammals to better understand how the seamount is linked to surrounding ecosystems. The summit area of Walters shoal is very shallow; and this will enable scientists to dive on the seamount, observe and collect species by hand rather than relying on robots as they did during previous expeditions. The expedition is to set out from Le Port, Reunion Island on April 23rd. Planned arrival date in Durban, South Africa is May 18th, after three and a half weeks at sea. Scientists will spend around 19 days exploring the seamount. The expedition will be undertaken in the Walters Shoal, which is a group of submerged mountains in the Western Indian Ocean, on the Madagascar Ridge, 450 nautical miles south of Madagascar, & 700 nautical miles east of South Africa. The summits rise to at least 500m below the water surface and extend over an area of 400km. The maximum summit height is 4,750m – around 60m short of the Mont Blanc. The expedition will set out from Le Port, Reunion Island, and end in Durban, South Africa. To answer the question as to why such an expedition needs to be undertaken, this is what François Simard, Deputy Director of IUCN’s Marine Programme says – “ Seamounts are islands of marine life with an important role in maintaining the health of the ocean. They contribute to food security by supporting fish stocks, and the unique species they harbour could provide genetic material for the development of future medicines. Yet they face increasing threats from unsustainable fishing and deep sea mining, and remain largely unexplored. We urgently need more research into these hotspots of marine biodiversity or we risk losing species that we didn’t even know existed.” Seamounts are home to many endemic, slow-growing, slow-reproducing species, and are highly vulnerable to intense fishing practices such as bottom trawling; both commercial and recreational fishing take place on Walters Shoal, including illegal fishing. Seamounts have the potential to contribute to the development of new medicines through the use of marine genetic resources from the many unique species they support. Seamounts play an important and only partially understood role in marine ecosystems well beyond the seamounts themselves; damage to seamounts could have widespread effects on ocean health and fisheries. Fewer than 300 out of the world’s 200,000 seamounts have been explored so far. Scientists will explore the fauna of the seamount and its role in the surrounding ecosystem. They will also investigate the effects of unsustainable fishing practices and exploration for future deep sea mining on the seamount ecosystem.Walters Shoal has particularly shallow summits – some only 18 metres below the ocean surface – while the summits of seamounts are usually 1000-2000m below the surface; this will enable scientists to dive on the seamount rather than relying on subsea robots as during previous expeditions, allowing for hands-on data collection and better observation of marine life. Like most seamounts, the Walters Shoal lies within areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) – marine areas covered by fragmented legal frameworks which leave their biodiversity vulnerable to growing threats. By improving our understanding of seamount ecosystems, this project aims to inform on-going discussions towards an implementing agreement to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The Project is led by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – Global Marine and Polar Programme. Scientific project partners: Muséum National de l’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD) Vessel chartered by the Institut Polaire Français (IPEV) The project is financed by the Fonds Français pour l’Environnement Mondial “Walters Shoal” Expedition The “Walters Shoal” expedition is bringing to fruition the objectives of the scientific component of the IUCN FFEM-SWIO project. In addition to the scientific aspects, the expedition aims to raise awareness about these important issues. Thus, it will serve as a basis for the development of a scientific documentary and an educational program.

Marianne Furtado de Nazareth is the former Assistant Editor, The Deccan Herald, adjunct faculty, St. Joseph’s PG College of Media Studies & a PhD scholar at the Madurai Kamaraj University |

Read |

| April 22, 2017 |

Climate Change As Genocide

by Michael T Klare, in Climate Change, Countercurrents.org  Not since World War II have more human beings been at risk from disease and starvation than at this very moment. On March 10th, Stephen O’Brien, under secretary-general of the United Nations for humanitarian affairs, informed the Security Council that 20 million people in three African countries—Nigeria, Somalia, and South Sudan—as well as in Yemen were likely to die if not provided with emergency food and medical aid. “We are at a critical point in history,” he declared. “Already at the beginning of the year we are facing the largest humanitarian crisis since the creation of the U.N.” Without coordinated international action, he added, “people will simply starve to death [or] suffer and die from disease.” Major famines have, of course, occurred before, but never in memory on such a scale in four places simultaneously. According to O’Brien, 7.3 million people are at risk in Yemen, 5.1 million in the Lake Chad area of northeastern Nigeria, 5 million in South Sudan, and 2.9 million in Somalia. In each of these countries, some lethal combination of war, persistent drought, and political instability is causing drastic cuts in essential food and water supplies. Of those 20 million people at risk of death, an estimated 1.4 million are young children. Despite the potential severity of the crisis, U.N. officials remain confident that many of those at risk can be saved if sufficient food and medical assistance is provided in time and the warring parties allow humanitarian aid workers to reach those in the greatest need. “We have strategic, coordinated, and prioritized plans in every country,” O’Brien said. “With sufficient and timely financial support, humanitarians can still help to prevent the worst-case scenario.” All in all, the cost of such an intervention is not great: an estimated $4.4 billion to implement that U.N. action plan and save most of those 20 million lives. The international response? Essentially, a giant shrug of indifference. To have time to deliver sufficient supplies, U.N. officials indicated that the money would need to be in pocket by the end of March. It’s now April and international donors have given only a paltry $423 million—less than a tenth of what’s needed. While, for instance, President Donald Trump sought Congressional approval for a $54 billion increase in U.S. military spending (bringing total defense expenditures in the coming year to $603 billion) and launched $89 million worth of Tomahawk missiles against a single Syrian air base, the U.S. has offered precious littleto allay the coming disaster in three countries in which it has taken military actions in recent years. As if to add insult to injury, on February 15th Trump told Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari that he was inclined to sell his country 12 Super-Tucano light-strike aircraft, potentially depleting Nigeria of $600 million it desperately needs for famine relief. Moreover,just as those U.N. officials were pleading fruitlessly for increased humanitarian funding and an end to the fierce and complex set of conflicts in South Sudan andYemen (so that they could facilitate the safe delivery of emergency food supplies to those countries), the Trump administration was announcing plans to reduce American contributions to the United Nations by 40%. It was also preparing to send additional weaponry to Saudi Arabia, the country most responsible for devastating air strikes on Yemen’s food and water infrastructure. This goes beyond indifference. This is complicity in mass extermination. Like many people around the world, President Trump was horrified by images of young children suffocating from the nerve gas used by Syrian government forces in an April 4th raid on the rebel-held village of Khan Sheikhoun. “That attack on children yesterday had a big impact on me—big impact,” he told reporters. “That was a horrible, horrible thing. And I’ve been watching it and seeing it, and it doesn’t get any worse than that.” In reaction to those images, he ordered a barrage of cruise missile strikes on a Syrian air base the following day. But Trump does not seem to have seen—or has ignored—equally heart-rending images of young children dying from the spreading famines in Africa and Yemen. Those children evidently don’t merit White House sympathy. Who knows why not just Donald Trump but the world is proving so indifferent to the famines of 2017? It could simply be donor fatigue or a media focused on the daily psychodrama that is now Washington, or growing fears about the unprecedented global refugee crisis and, of course, terrorism. It’s a question worth a piece in itself, but I want to explore another one entirely. Here’s the question I think we all should be asking: Is this what a world battered by climate change will be like—one in which tens of millions, even hundreds of millions of people perish from disease, starvation, and heat prostration while the rest of us, living in less exposed areas, essentially do nothing to prevent their annihilation? Famine, Drought, and Climate Change First, though, let’s consider whether the famines of 2017 are even a valid indicator of what a climate-changed planet might look like. After all, severe famines accompanied by widespread starvation have occurred throughout human history. In addition, the brutal armed conflicts now underway in Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen are at least in part responsible for the spreading famines. In all four countries, there are forces—Boko Haram in Nigeria, al-Shabaab in Somalia, assorted militias and the government in South Sudan, and Saudi-backed forces in Yemen—interfering with the delivery of aid supplies. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that pervasive water scarcity and prolonged drought (expected consequences of global warming) are contributing significantly to the disastrous conditions in most of them. The likelihood that droughts this severe would be occurring simultaneously in the absence of climate change is vanishingly small. In fact, scientists generally agree that global warming will ensure diminished rainfall and ever more frequent droughts over much of Africa and the Middle East. This, in turn, will heighten conflicts of every sort and endanger basic survival in a myriad of ways. In their most recent 2014 assessment of global trends, the scientists of the prestigious Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that “agriculture in Africa will face significant challenges in adapting to climate changes projected to occur by mid-century, as negative effects of high temperatures become increasingly prominent.” Even in 2014, as that report suggested, climate change was already contributing to water scarcity and persistent drought conditions in large parts of Africa and the Middle East. Scientific studies had, for instance, revealed an “overall expansion of desert and contraction of vegetated areas” on that continent. With arable land in retreat and water supplies falling, crop yields were already in decline in many areas, while malnutrition rates were rising—precisely the conditions witnessed in more extreme forms in the famine-affected areas today. It’s seldom possible to attribute any specific weather-induced event, including droughts or storms, to global warming with absolute certainty. Such things happen with or without climate change. Nonetheless, scientists are becoming even more confident that severe storms and droughts (especially when occurring in tandem or in several parts of the world at once) are best explained as climate-change related. If, for instance, a type of storm that might normally occur only once every hundred years occurs twice in one decade and four times in the next, you can be reasonably confident that you’re in a new climate era. It will undoubtedly take more time for scientists to determine to what extent the current famines in Africa and Yemen are mainly climate-change-induced and to what extent they are the product of political and military mayhem and disarray. But doesn’t this already offer us a sense of just what kind of world we are now entering? The Selective Impact of Climate Change In some popular accounts of the future depredations of climate change, there is a tendency to suggest that its effects will be felt more or less democratically around the globe—that we will all suffer to some degree, if not equally, from the bad things that happen as temperatures rise. And it’s certainly true that everyone on this planet will feel the effects of global warming in some fashion, but don’t for a second imagine that the harshest effects will be distributed anything but deeply inequitably. It won’t even be a complicated equation. As with so much else, those at the bottom rungs of society—the poor, the marginalized, and those in countries already at or near the edge— will suffer so much more (and so much earlier) than those at the top and in the most developed, wealthiest countries. As a start, the geophysical dynamics of climate change dictate that, when it comes to soaring temperatures and reduced rainfall, the most severe effects are likely to be felt first and worst in the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Latin America—home to hundreds of millions of people who depend on rain-fed agriculture to sustain themselves and their families. Research conducted by scientists in New Zealand, Switzerland, and Great Britain found that the rise in the number of extremely hot days is already more intense in tropical latitudes and disproportionately affects poor farmers. Living at subsistence levels, such farmers and their communities are especially vulnerable to drought and desertification. In a future in which climate-change disasters are commonplace, they will undoubtedly be forced to choose ever more frequently between the unpalatable alternatives of starvation or flight. In other words, if you thought the global refugee crisis was bad today, just wait a few decades. Climate change is also intensifying the dangers faced by the poor and marginalized in another way. As interior croplands turn to dust, ever more farmers are migrating to cities, especially coastal ones. If you want a historical analogy, think of the great Dust Bowl migration of the “Okies” from the interior of the U.S. to the California coast in the 1930s. In today’s climate-change era, the only available housing such migrants are likely to find will be in vast and expanding shantytowns (or “informal settlements,” as they’re euphemistically called), often located in floodplains and low-lying coastal areas exposed to storm surges and sea-level rise. As global warming advances, the victims of water scarcity and desertification will be afflicted anew. Those storm surges will destroy the most exposed parts of the coastal mega-cities in which they will be clustered. In other words, for the uprooted and desperate, there will be no escaping climate change. As the latestIPCC report noted, “Poor people living in urban informal settlements, of which there are [already] about one billion worldwide, are particularly vulnerable to weather and climate effects.” The scientific literature on climate change indicates that the lives of the poor, the marginalized, and the oppressed will be the first to be turned upside down by the effects of global warming. “The socially and economically disadvantaged and the marginalized are disproportionately affected by the impacts of climate change and extreme events,” the IPCC indicated in 2014. “Vulnerability is often high among indigenous peoples, women, children, the elderly, and disabled people who experience multiple deprivations that inhibit them from managing daily risks and shocks.” It should go without saying that these are also the people least responsible for the greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming in the first place (something no less true of the countries most of them live in). Inaction Equals Annihilation In this context, consider the moral consequences of inaction on climate change. Once it seemed that the process of global warming would occur slowly enough to allow societies to adapt to higher temperatures without excessive disruption, and that the entire human family would somehow make this transition more or less simultaneously. That now looks more and more like a fairy tale. Climate change is occurring far too swiftly for all human societies to adapt to it successfully. Only the richest are likely to succeed in even the most tenuous way. Unless colossal efforts are undertaken now to halt the emission of greenhouse gases, those living inless affluent societies can expect to suffer from extremes of flooding, drought, starvation, disease, and death in potentially staggering numbers. And you don’t need a Ph.D. in climatology to arrive at this conclusion either. The overwhelming majority of the world’s scientists agree that any increase in average world temperatures that exceeds 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above the pre-industrial era—some opt for a rise of no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius—will alter the global climate system drastically. In such a situation, a number of societies will simply disintegrate in the fashion of South Sudan today, producing staggering chaos and misery. So far, the world has heated up by at least one of those two degrees, and unless we stop burning fossil fuels in quantity soon, the 1.5 degree level will probably be reached in the not-too-distant future. Worse yet, on our present trajectory, it seems highly unlikely that the warming process will stop at 2 or even 3 degrees Celsius, meaning that laterin this century many of the worst-case climate-change scenarios—the inundation of coastal cities, the desertification of vast interior regions, and the collapse of rain-fed agriculture in many areas—will become everyday reality. In other words, think of the developments in those three African lands and Yemen as previews of what far larger parts of our world could look like in another quarter-century or so: a world in which hundreds of millions of people are at risk of annihilation from disease or starvation, or are on the march or at sea, crossing borders, heading for the shantytowns of major cities, looking for refugee camps or other places where survival appears even minimally possible. If the world’s response to the current famine catastrophe and the escalating fears of refugees in wealthy countries are any indication, people will die in vast numbers without hope of help. In other words, failing to halt the advance of climate change—to the extent that halting it, at this point, remains within our power—means complicity with mass human annihilation. We know, or at this point should know, that such scenarios are already on the horizon. We still retain the power, if not to stop them, then to radically ameliorate what they will look like, so our failure to do all we can means that we become complicitin what—not to mince words— is clearly going to be a process of climate genocide. How can those of us in countries responsible for the majority of greenhouse gas emissions escape such a verdict? And if such a conclusion is indeed inescapable, then each of us must do whatever we can to reduce our individual, community, and institutional contributions to global warming. Even if we are already doing a lot—as many of us are —more is needed. Unfortunately, we Americans are living not only in a time of climate crisis, but in the era of President Trump, which means the federal government and its partners in the fossil fuel industry will be wielding their immense powers to obstruct all imaginable progress on limiting global warming. They will be the true perpetrators ofclimate genocide. As a result, the rest of us bear a moral responsibility not just to do what we can at the local level to slow the pace of climate change, but also to engage in political struggle to counteract or neutralize the acts of Trump and company. Only dramatic and concerted action on multiple fronts can prevent the human disasters now unfolding in Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen from becoming the global norm. Michael T. Klare is the Five College Professor of Peace and World Security Studies at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts. His newest book, The Race for What’s Left: The Global Scramble for the World’s Last Resources, has just recently been published. His other books include: Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: The New Geopolitics of Energy andBlood and Oil: The Dangers and Consequences of America’s Growing Dependence on Imported Petroleum. A documentary version of Blood and Oil is available from the Media Education Foundation. |

Read |

| April 22, 2017 |

Saving The Amazon Reef

by Marianne de Nazareth, in Environmental Protection, Countercurrents.org The Great Barrier Reef on the north-east coast of Australia which contains the world’s largest collection of coral reefs, has been the only reef which has been in the news of late and has a UNESCO heritage label. Today with oceans heating up reefs are threatened and the world holds its breath, hoping to reverse the trend. Interestingly, a newly discovered reef, the Amazon Reef, spread over 9500 km, at the mouth of the Amazon River is receiving focussed attention from the IUCN and marine scientists. It is important because it is like no other coral reef that we know of. While other reefs exist in clear, sunlit waters, the Amazon Reef lies in very muddy, sediment-filled waters of the Amazon, and is a product of unusual chemosynthesis. The reef lies in a uniquely bio- diverse area, and as scientists explore this area further, new exciting species of life are likely to be discovered. The reef, which also serves as a natural carbon sink, is surrounded by the largest mangrove stretch in the world, which again is another massive natural carbon sink. Any threat to the reef will directly affect the earth’s ability to remove carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere (carbon sequestration) Now, oil companies have plans to drill around 15 to 20 billion barrels of oil from the surrounding area, which, once up for consumption, will further adversely affect efforts to mitigate climate change and destroy this pristine habitat. This is where Greenpeace India has stepped in with the goal of stopping oil exploration near the mouth of the Amazon river and guarantee that the ecosystem of the region, and its vital mangrove carbon sinks, will remain intact and protected.

Ravi Chellam, Executive Director, Greenpeace India, ” I strongly believe that our interactions with Nature, our environment and fellow human beings have to be based on a robust ethical foundation. We, both as individual human beings and collectively as the human race have no right to damage and destroy any part of nature, especially if our actions will result in extinction of species as extinction is forever! The case of the newly discovered Amazon reef is particularly compelling for us to take global and collective responsibility for it. This reef is quite expansive in its scale, occupying at least 9,500 sq km and very unique in its location, at the mouth of the Amazon River and in muddy waters. Currently we have barely documented 5% of these reefs and it would be unpardonable if we allow any damage to these reefs in the name of “development”. I find it particularly distressing that the proposed development is for oil drilling when the dangers posed by global warming and climate change are increasingly becoming part of our daily lives. If the global community has to deliver on the pledges made as part of the Paris Agreement, any future exploration for hydrocarbons, especially in biodiversity rich sites like the Amazon Reefs should be prevented.”

The Amazon Reef is an ecosystem composed of corals, sponges and rhodoliths (calciferous algae). In the southern part of the Reef, there are mainly sponges, some of them are over 2 meters in length.In the 70’s, scientists speculated about the existence of a reef in the region, but no further research was done. Then from 2010 to 2014, scientists went on three expeditions to collect samples and study their findings. This system of corals, sponges and rhodoliths was revealed in April of 2016. Because of its characteristics and extreme conditions , this system of corals is unique. Its discovery was celebrated by specialists as one of the most important in marine biology in recent decades. According to Ronaldo Francini, one of the scientists who revealed the Reef to the world, “this is clearly a hotspot for biodiversity”. The campaign will hasten the end of the oil age and maintaining global temperatures within 1.5C degrees and contribute to the erosion of political and economic power currently held by fossil fuel corporations globally by weakening their relationships with governments, customers and investors and undermining their social license. The common man is being made more aware of these issues through online campaigns and what is known as ‘clicktivism’. The Amazon Reef Campaign has crossed 1 million signups globally. The fight to protect our natural treasures, functional ecosystems and a better world is gathering momentum in one more corner of the globe. Greenpeace India is very much part of this global campaign, we have received 3000 sign ups and counting within just four days of the launch of the campaign. Greenpeace India launched the Amazon Reef Campaign on 13th April and is running successfully. Several big names including, Leonard di Caprio, supports the Amazon reef campaign. “The reef is a new biome, located in a place where it was thought not possible for reefs to exist – they are located in the mouth of the Amazon basin, where there is a lot of sediments brought by the river (largest in the world in volume of water), there are spots where only 2% of light passes through. So it is a new biome that needs to be studied as is very important for marine biodiversity and fish stocks. At the same time, this area is risky to drill for oil – from 95 attempts to produce oil in the mouth of the Amazon basin since the 1960s, 27 failed due to mechanical accidents, while the other attempts either didn’t find anything, or the reserves weren’t technically or economically viable. So it is a new frontier of oil and we can’t access new reserves, where already have more oil reserves guaranteed in the world than we can burn if we want to keep climate warming to 1.5C.

Regarding the mangroves, they are not linked to the reef, but both mangroves and reefs play a very important role in biodiversity and carbon capture. The largest continuous mangrove in the world is on the coast of Amapá and if oil destroyed it, there is no technology to clean it up. And the mangroves play an important role in both marine and land biodiversity in the coast, extremely important for artisanal fishing communities – the coast of Amapá is home to several traditional communities, fishing, extractivist, indigenous and quilombola (former slaves from the 18th and 19th centuries that ran away). Plus, coral systems are very susceptible to the impacts of climate change. Between the atmosphere and the ocean, there is an exchange of gases, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2), which is absorbed, and oxygen, which is released by the action of the algae. As we are emitting large amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, the oceans are having to absorb much of this gas in a short period of time, which throws the system out of balance. One of the effects of this excess CO2 is that the ocean is becoming more acidic. And acidity harms mollusks and corals, which are unable to form with the same amount of carbonates. As an analogy, it is as if the ocean has osteoporosis. A study published in Nature Climate Change shows that in corals reefs, the diversity and complexity of marine life falls as the acidity of the water rises. Species that use calcium carbonate to build their shells and skeletons, like mussels and corals, are particularly vulnerable to acidification. In addition, the areas surrounding mangroves and corals are inhabited by species of turtles, marine mammals, etc., that, we know today, play an important role in the sequestration of carbon in the ocean. Oil exploration involves seismic surveys. The waves stun marine animals and diving birds, interfering with their navigation and communication abilities. This can be deadly for individuals and species. The drilling process also involves large volumes of waste being produced. This includes extracted water mixed with oil and other contaminants, drilling “muds” (including toxic chemicals and heavy metals) to cool and lubricate the equipment and other forms of industrial waste. These inevitably end up in the ocean and are ingested by marine life of all sizes. Some of the tiniest marine creatures, foundational to our ecosystems, the plankton, are particularly susceptible to crude oil pollution and suffer population reductions. Oil companies are estimated to drill around 15 to 20 billion barrels of oil from the surrounding area, which, once up for consumption, will contribute immensely to global warming and adversely affect efforts to mitigate climate change. So we need to support the campaign, save the reef and stop the drilling. Marianne Furtado de Nazareth is the former Assistant Editor, The Deccan Herald, adjunct faculty, St. Joseph’s PG College of Media Studies & a PhD scholar at the Madurai Kamaraj University |

Read |

| April 24, 2017 |

Our Common Oceans And Seas

by Rene Wadlow, in Counter Solutions, Countercurrents.org  The United Nations is currently preparing a world conference 5-7 June 2017 devoted to the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal N° 14: Conserve and sustainable use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development. Non-governmental organizations in consultative status with the U.N. are invited to submit recommendations for the governmental working group which is meeting 24 to 27 April in New York. The Association of World Citizens has long been concerned with the Law of the Sea and had been active during the 10-year negotiations on the law of the sea during the 1970s, the meetings being held one month a year, alternatively in New York and Geneva. The world citizens position for the law of the sea was largely based on a three-point framework: a) that the oceans and seas were the common heritage of humanity and should be seen as a living symbol of the unity of humanity; b) that ocean management should be regulated by world law created as in as democratic manner as possible; c) that the wealth of the oceans, considered as the common heritage of mankind should contain mechanisms of global redistribution, especially for the development of the poorest, a step toward a more just economic order, on land as well as at sea. The concept of the oceans as the common heritage of humanity had been introduced into the U.N. awareness by a moving speech in the U.N. General Assembly by Arvid Pardo, Ambassador of Malta in November 1967. Under traditional international sea law, the resources of the oceans, except those within a narrow territorial sea near the coast line were regarded as “no one’s property” or more positively as “common property.” The “no one’s property” opened the door to the exploitation of resources by the most powerful and the most technologically advanced States. The “common heritage” concept was put forward as a way of saying that “humanity” – at least as represented by the States in the U.N. – should have some say as to the way the resources of the oceans and seas should be managed. Thus began the 1970s Law of the Seas negotiations. Perhaps with or without the knowledge of Neptune, lord of the seas, the Maltese voted to change the political party in power just as the sea negotiations began. Arvid Pardo was replaced as Ambassador to the U.N. by a man who had neither the vision nor the diplomatic skills of Pardo. Thus, during the 10 years of negotiations the “common heritage” flame was carried by world citizens, in large part by Elisabeth Mann Borgese with whom I worked closely during the Geneva sessions of the negotiations. Elisabeth Mann Borgese (1918-2002) whose birth anniversary we mark on 24 April, was a strong-willed woman. She had to come out from under the shadow of both her father, Thomas Mann, the German writer and Nobel laureate for Literature, and her husband Giuseppe Antonio Borgese (1882-1952), Italian literary critic and political analyst. From 1938, Thomas Mann lived in Princeton, New Jersey and gave occasional lectures at Princeton University. Thomas Mann, whose novel The Magic Mountain was one of the monuments of world literature between the two World Wars, always felt that he represented the best of German culture against the uncultured mass of the Nazis. He took himself and his role very seriously, and his family existed basically to facilitate his thinking and writing. Borgese had a regular professor’s post at the University of Chicago but often lectured at other universities on the evils of Mussolini. Borgese, who had been a leading literary critic and university professor in Milan, left Italy for the United States in 1931 when Mussolini announced that an oath of allegiance to the Fascist State would be required of all Italian professors. For Borgese, with a vast culture including the classic Greeks, the Renaissance Italians, and the 19th century nationalist writers, Mussolini was an evil caricature which too few Americans recognized as a destructive force in his own right and not just as the fifth wheel of Hitler’s armed car. G.A. Borgese met Elizsabeth Mann on a lecture tour at Princeton, and despite being close to Thomas Mann in age, the couple married very quickly shortly after meeting. Elisabeth moved to the University of Chicago and was soon caught up in Borgese’s efforts to help the transition from the Age of Nations to the Age of Humanity. For Borgese, the world was in a watershed period. The Age of Nations − with its nationalism which could be a liberating force in the 19th century as with the unification of Italy − had come to a close with the First World War. The war clearly showed that nationalism was from then on only the symbol of death. However, the Age of Humanity, which was the next step in human evolution, had not yet come into being, in part because too many people were still caught in the shadow play of the Age of Nations. Since University of Chicago scientists had played an important role in the coming of the Atomic Age, G.A. Borgese and Richard McKeon, Dean of the University felt that the University should take a major role in drafting a world constitution for the Atomic Age. Thus the Committee to Frame a World Constitution, an interdisciplinary committee under the leadership of Robert Hutchins, head of the University of Chicago, was created in 1946. To re-capture the hopes and fears of the 1946-1948 period when the World Constitutions was being written, it is useful to read the book written by one of the members of the drafting team: Rexford Tugwell. A Chronicle of Jeopardy (University of Chicago Press, 1955). The book is Rex Tugwell’s reflections on the years 1946-1954 written each year in August to mark the A-bombing of Hiroshima Elisabeth had become the secretary of the Committee and the editor of its journal Common Cause. The last issue ofCommon Cause was in June 1951. G.A. Borgese published a commentary on the Constitution, dealing especially with his ideas on the nature of justice. It was the last thing he wrote, and the book was published shortly after his death: G.A.Borgese. Foundations of the World Republic (University of Chicago Press, 1953). In 1950, the Korean War started. Hope for a radical transformation of the UN faded. Borgese and his wife went to live in Florence, where weary and disappointed, he died in 1952. The drafters of the World Constitution went on to other tasks. Robert Hutchins left the University of Chicago to head a “think tank”- Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions – taking some of the drafters, including Elisabeth, with him. She edited a booklet on the Preliminary Draft with a useful introduction A Constitution for the World (1965) However, much of the energy of the Center went into the protection of freedom of thought and expression in the USA, at the time under attack by the primitive anti-communism of then Senator Joe McCarthy. In the mid-1950s, from world federalists and world citizens came various proposals for UN control of areas not under national control: UN control of the High Seas and the Waterways, especially after the 1956 Suez Canal conflict, and of Outer Space. A good overview of these proposals is contained in James A. Joyce. Revolution on East River (New York: Ablard-Schuman, 1956). After the 1967 proposal of Arvid Pardo, Elisabeth Mann Borgese turned her attention and energy to the law of the sea. As the UN Law of the Sea Conference continued through the 1970s, Elisabeth was active in seminars and conferences with the delegates, presenting ideas, showing that a strong treaty on the law of the sea would be a big step forward for humanity. Many of the issues raised during the negotiations leading to the Convention, especially the concept of the Exclusive Economic Zone, actively battled by Elisabeth but actively championed by Ambassador Alan Beesley of Canada, are with us today in the China seas tensions. While the resulting Convention of the Law of the Sea has not revolutionized world politics – as some of us hoped in the early 1970s – the Convention is an important building block in the development of world law. We are grateful for the values and the energy that Elisabeth Mann Borgese embodied and we are still pushing for the concept of the common heritage of humanity. Rene Wadlow, President and a representative to the United Nations, Geneva, Association of World Citizens |

Read |

| May 15, 2017 |

The Future Is A Pluriverse