Theme for this month

Whole paper concerning the theme.

Chapter I. Front page promoting the 21st vision of Global Community.

AnimationChapter II. Global Community 21st century vision of Global Civilization.

Text in the animation of Chapter I

Images in the animation of Chapter I

AnimationChapter III. Global cooperation, issues, and dialogue.

Text in the animation of Chapter II

Images in the animation of Chapter II

AnimationChapter IV. Rights, Global Law, and Global Parliament.

Text in the animation of Chapter III

Images in the animation of Chapter III

AnimationChapter V. Ethics, religions, faith, and peace.

Text in the animation of Chapter IV

Images in the animation of Chapter IV

Animation

Text in the animation of Chapter V

Images in the animation of Chapter V

Chapter I. Front page promoting the 21st vision of Global Community.

Animation of Front page promoting the 21st vision of Global Community.

Text in the animation of Chapter I

In this millennium, the affairs of humanity appeared to be unfolding in more profound ways. We can no longer perceive ourselves as a People who could survive alone and a People who does not need anyone else. We belong and depend to a much larger group, that of Global Community, the human family. The 21st Century will see limitless links and interrelationships between the Global Community and the build up of Global Civilization. New standards, goals and objectives are being defined. Firm universal guidelines are essentials to keep the world healthy. Already we notice new ways of thinking being embraced, new behaviors and attitudes adopted. Global ethics are now required to do business and deal with one another to sustain Earth.

Let our time this generation be a time remembered for the awakening of a new reverence for life, the firm resolve to achieve sustainability, the quickening of the struggle for justice and peace, and the joyful celebration of life. Let us build up Global Civilization.

| Day data received | Theme or issue | Read article or paper |

|---|---|---|

| July 5, 2016 |

Russia’s Achilles Heel – Reflections from St. Petersburg

by F. William Engdahl, Information Clearing House

For three days this month, June 16-18, I had the

opportunity to participate as a panelist in the

annual St. Petersburg International Economic Forum

in Russia. I’ve been in Russia many times since the

Ukraine US-backed coup d’état of February 2014, and

the deliberate escalations of NATO military and

economic tensions and sanctions against the Russian

Federation. This year’s forum, my second as

participant, gave me a rare opportunity to speak

with leading representatives from every sector of

the Russian economy- from CEOs of the energy sector

to the Russian Railways to the national Russia Grid

electricity provider to numerous small and mid-sized

businessmen, to a wide range of economists. It

sharpened my perception of just how precarious the

situation of Russia today is.

What became clearer to me in the course of the three days of discussions in St Petersburg is precisely how vulnerable Russia is. Her Achilles Heel is the reigning ideology that controls every key economic post of the Government of the Russian Federation under Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev. Under the terms of the Russian Constitution adopted in the chaos of the Yeltsin years and enormously influenced, if not literally drafted, by Russia’s foreign IMF advisers, economic policy is the portfolio responsibility of the Prime Minister and his various ministers of Economics, Finance and so forth. The Russian President, today Vladimir Putin, is responsible for defense and foreign policy. Making the job virtually impossible of reviving credit flows to fuel genuine real investment in urgently needed infrastructure across the vast land expanse of Russia is the Central Bank of Russia. The Central Bank of Russia was given two constitutionally-mandated tasks when it was created as an entity independent from the Russian Government in the first months of the Russian Federation following the breakup of the Soviet Union. It must control Russian domestic inflation and it must stabilize the Ruble against major foreign currencies. Like western central banks, its role is almost purely monetary, not economic. In June, 2015 as I participated the first time in the St Petersburg forum, the Russian Central Bank base rate, interest charged to banks, was 11%. In the peak of the so-called Ruble crisis in January 2015 it had reached 17%. Expectations last summer were that Elvira Nabiullina, the central bank governor since 2013, would begin to bring central rates rather rapidly down to manageable levels, especially at a time when central banks such as the European Central Bank, the US Fed and the Bank of Japan were lowest in some 500 years at zero or even negative. Further, since January 2016 oil prices, a significant factor in the Ruble strength as Russia is the world’s largest oil exporter, began a rise of more than 60% from lows below $30 a barrel in early January to levels near $50 six months later. That lowering of rates by the Central Bank hasn’t happened. Instead it is slowly killing the economy. One year later, in early June, 2016 the Russian Central Bank under Governor Nabiullina made the first rate cut since June 2015…to a still-deadly 10.5%. Perhaps it’s notable that monetarist Nabiullina was named by the London Euromoney magazine as their 2015 Central Bank Governor of the Year. That should be seen as a bad omen for Russia. Equally ominous was the fulsome praise the head of Washington’s IMF had for Nabiullina’s monetarist handling of the early 2015 Ruble crisis. Operation Success…patient died What I experienced in my discussions at the conference–this year with record attendance of more than 12,000 business people and others from around the world–was a sense that there coexist two Russian governments, each the polar opposite of the other. Every key economic and finance post is firmly occupied at present by monetarist free-market liberal economists who might be called “Gaidar’s Kindergarten.” Yegor Gaidar was the architect, along with Harvard’s Jeffrey Sachs, a Soros-backed economist, of the radical “shock therapy” that was responsible for the economic hardships that plagued the country in the 1990s resulting in mass poverty and hyperinflation. Today’s Gaidar Kindergarten includes former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, another Euromoney favorite in 2010 as international Finance Minister of the Year. It includes Economics Minister, Alexey Ulyukaev. It also includes Medvedev’s Deputy Prime Minister, Arkady Dvorkovic. Dvorkovic, a graduate of Duke University in North Carolina, is a protégé, directly serving during his earlier years under Yegor Gaidar. In 2010 under then Russian President Medvedev, Dvorkovic proposed a lunatic scheme to make Moscow into a world financial center by bringing in Goldman Sachs and the major Wall Street banks to set it all up. We might call it inviting the fox into the hen house. Dvorkovic’s economic credo is “Less state!” He was the chief lobbyist in Russia’s WTO accession campaign, and tried to ram through rapid privatization of the assets that remain state-owned. This is the core group around Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev today who are strangling any genuine Russian economic recovery. They follow the western playbook written in Washington by the International Monetary Fund and the US Treasury. Whether they do this at this stage out of honest conviction that that is best for their nation or out of a deep psychological hatred for their country, I’m not in a position to say. The effects of their policies, as I learned in my many discussions this month in St Petersburg are devastating. In effect, they are self-imposing economic sanctions on Russia far worse than any from the USA or EU. If Putin’s United Russia party loses the elections on 18 September, it will be due not to his foreign policy initiatives for which he still enjoys 80+% popularity polls. It will be because Russia has not cleaned the Augean Stables of the Gaidar Kindergarten. Obeying Washington Consensus From various discussions I learned to my shock that the official policy of Medvedev’s economic team and of the Central Bank today is to follow the standard IMF “Washington Consensus” budget austerity policies. This is so despite the fact that Russia, years ago, repaid its IMF loans and is no longer under IMF “conditionalities,” as it was during the 1998 Ruble default crisis. Not only that, Russia has one of the lowest debt-to-GDP ratios of state debt of any major country in the world, a mere 17% while the USA “enjoys” a 104% ratio, the Eurozone countries have an average debt level of over 90% of GDP, far from the mandated 60% Maastricht level. Japan has a staggering 229% debt-to-GDP. The official economic policy today of the Central Bank of Russia with its absurdly high rates is to reduce an inflation rate of a mere 8% to its target of 4% through an explicit policy of budget austerity and consumption reduction. No economy in recorded history has managed an economic policy under forced reduction of consumption, certainly not Greece nor any African nation. Yet the Russian Central Bank, as if on automatic pilot, religiously sings the Gregorian death chants of the IMF as if they were a magic formula. If Russia continues down this Central Bank monetarist path it may well soon be that, “the operation was a success, but the patient died,” as the cynical saying goes. Stolypin Club There is a coherent, experienced and growing opposition to this liberal western cabal around Medvedev. They at present are represented in something called the Stolypin Club, created by a group of Russian national economists in 2012 to draft comprehensive alternative strategies to lessen Russia’s dependence on the dollar world and boost growth of the real economy. I had the honor of appearing on a major panel together with several members and founders of this group. It included a co-founder of the Stolypin Club, Boris Titov, a Russian businessman and open ideological foe of Kudrin, who is chairman of the All-Russian “Business Russia” organization. He insists on the need to increase domestic production of goods, stimulate demand, attracting investment, tax cuts and the cuts to the refinancing rate of the Central Bank. Titov is a central figure today in Russia’s recent China initiatives. He served as chairman of the Russian part of the Russian-Chinese Business Council, and member of the Presidium of the National Council on Corporate Governance. My panel also included Stolypin Club leading members Sergei Glazyev, Adviser to the President of the Russian Federation, and Andrey Klepach, Deputy Chairman of the VEB Bank for Development. Klepach, a co-founder of the Stolypin Club, was formerly Deputy Economics Minister of Russia, and director of the macroeconomic forecasting department of the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade. My impression was that these are serious, dedicated people who understand that the heart of true national economic policy is human capital and human well-being not inflation or other econometric data. Stolypin Bonds At this point, expanding on my remarks to the audience in St. Petersburg, I would like to share a proposal for getting Russia’s vast and rich economy and people into a positive growth path despite sanctions and high central bank interest rates. All the necessary elements are there. The country has the largest land expanse of any nation in the world. It has arguably the richest untapped mineral and precious metals resources. It has some of the finest scientific and engineering minds in the world, a skilled workforce, highly intelligent wonderful people. What is lacking is the coordination of all the instruments to make an harmonic national economic symphony. Still there is a fear of being accused of reversion to Soviet Gosplan central planning among too many in Government positions. Only partly are the scars of Russia’s national trauma much healed under the years of Putin, someone who has allowed Russians to again feel respected in the world. The scars came not only from the travails of communism. They came from the manner in which the United States under President George H.W. Bush in the early 1990’s and after under every US president since, has gone out of its way to humiliate and heap contempt on Russia and everything Russian. Sadly, those scars, consciously or unconsciously, still hamper many in positions of responsibility across Russia. On the positive side, there are many successful models of growing an economy in a positive, debt-free manner. One is Germany following the World War in the 1950’s through the state special credit authority, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (The Credit Authority for Redevelopment), which restored Germany from the ashes of war with subsidized interest rates. It was also used to rebuild the former German Democratic Republic after unification in 1990. There is the successful model in the 1960s under French President Charles de Gaulle, called Planification, where every region with representatives of all major social groups—farmers, small-to-midsize businesses, labor, large companies—met and debated their regional priorities and sent them to a central body to draft the Five Year Plan. Five years not because of Soviet imitation but because major infrastructure requires a minimum of five years and the possible correction of ineffective or outdated plans needs a short span of five years. I would propose establishing of a unique, separate State Authority for National Infrastructure Development, independent of the Central Bank of Russia or of the Finance Ministry. It ideally would have an impartial overseeing board of most respected and economically experienced Russian nationals from each region. Perhaps it would make sense to place it directly under the responsibility of the President. It could adopt the “best practices” of the above two models as well as others successful in recent years such as South Korea after the 1950’s. The model developed by Russia’s Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin, the namesake of the Stolypin Club group of national economists today, is appropriate. As Czar Nicholas II’s appointed chairman of the Council of Ministers, Stolypin served as both Prime Minister and Minister of Internal Affairs from 1906 to 1911. He introduced successful land reforms to create a class of market-oriented smallholding landowners, and construction of a second track of Sergei Witte’s monumental Trans-Siberian Railway, one along the Amur River border with China. He began to transform Russia’s economy dramatically. I would propose the suggested separate State Authority for National Infrastructure Development be given the authority to issue special “Stolypin Bonds” to finance a wide variety of agreed national infrastructure projects that would rapidly accelerate the Eurasian economic integration and creation of vast new markets with China, Kazakhstan, Belarus on to India and Iran. The Stolypin Bonds would be issued to only Russian nationals, pay an attractive and fair interest rate, and not transferable to foreign bondholders. Because of this internal financing, it would not be vulnerable to western financial warfare. The debt incurred would not be any problem because of the quality of the investment and because of the present extraordinary low debt levels of the Russian State. Emergency conditions require extraordinary solutions. Sale of the special bonds would be direct from the new state authority, and not via banks, thus increasing the possible interest rate attractiveness for the Russian population. Bonds could be distributed to the public through the national network of Post Offices, minimizing distribution costs. As was done in Germany and other countries previously with great success, the bonds could be collateralized by something Russia has more of than anyone—its land. Because the bonds go exclusively to infrastructure projects deemed national priority, they would be anti-inflationary. This is because of the “secret” of government infrastructure investment. By making the arteries of the national economy flow more efficiently across all Russia, where today, for lack of modern infrastructure, none exist. They will create new markets, significantly lower transportation costs. The new enterprises and the newly-created jobs to construct the infrastructure will repay the State Budget manifold in raised tax revenues for a prospering economy. It is the opposite of the current, failed Central Bank “consumption-reduction” anti-inflation model. This expanding investment in turn would undercut current Central Bank power over the national economy until such time the members of the Duma realize it is time to roll-back the 1991 Central Bank law and reincorporate it into the state. State sovereign control over its money is one of the most essential attributes of sovereignty. Objectively, today Russia possesses everything she needs to become an economically prosperous world economic giant and technology pacesetter in addition to her already made decision to become world leading agriculture exporter of GMO-free, natural agriculture. What was clear from my St Petersburg talks this time is that events are approaching a decisive “do or die” turn in which either economic policy is formally put into the hands of competent national economy circles such as those of Boris Titov, Andrey Klepach and Sergey Glazyev, or she will succumb to the insidious poison of Washington Consensus and liberal free market nonsense. After my recent private talks I am optimistic regarding prospects for a positive change. F. William Engdahl is strategic risk consultant and lecturer, he holds a degree in politics from Princeton University and is a best-selling author on oil and geopolitics, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook” |

Read |

| June 28, 2016 |

The Age of Disintegration: Neoliberalism, Interventionism, The Resource Curse, And A Fragmenting World

by Patrick Cockburn, American Imperialism, Countercurrents.org  We live in an age of disintegration. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Greater Middle East and Africa. Across the vast swath of territory between Pakistan and Nigeria, there are at least seven ongoing wars — in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Libya, Somalia, and South Sudan. These conflicts are extraordinarily destructive. They are tearing apart the countries in which they are taking place in ways that make it doubtful they will ever recover. Cities like Aleppo in Syria, Ramadi in Iraq, Taiz in Yemen, and Benghazi in Libya have been partly or entirely reduced to ruins. There are also at least three other serious insurgencies: in southeast Turkey, where Kurdish guerrillas are fighting the Turkish army, in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula where a little-reported but ferocious guerrilla conflict is underway, and in northeast Nigeria and neighboring countries where Boko Haram continues to launch murderous attacks. All of these have a number of things in common: they are endless and seem never to produce definitive winners or losers. (Afghanistan has effectively been at war since 1979, Somalia since 1991.) They involve the destruction or dismemberment of unified nations, their de facto partition amid mass population movements and upheavals — well publicized in the case of Syria and Iraq, less so in places like South Sudan where more than 2.4 million people have been displaced in recent years.

|

Read |

| June 28, 2016 |

Atmospheric CO2 Level May Not Drop Below 400 ppm “Within Our Lifetimes”

by Yale Environment 360, Climate Change, Countercurrents.org

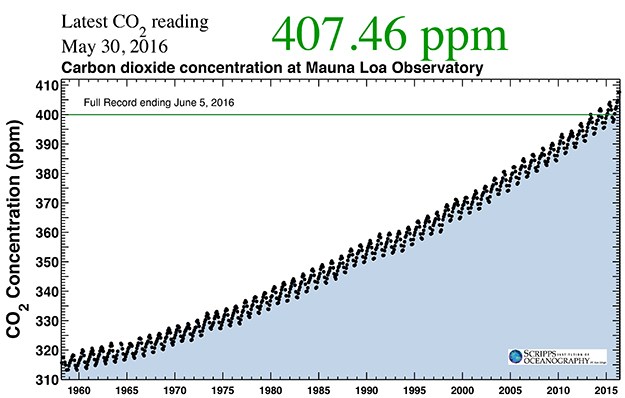

NOAA CO2 measurements taken at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, known as the Keeling Curve. CO2 concentrations have risen from 312ppm in 1958 to 407ppm today.

Atmospheric concentrations of CO2 will stay permanently above 400 parts per million (ppm) this year due to El Nino—and will likely not drop below that number again “within our lifetimes,” according to a study published this week in the journal Nature. The milestone represents a symbolic threshold that scientists and environmentalists had long sought to avoid. Greenhouse gases have jumped 48 percent from the pre-industrial era, and 29 percent in just the past 60 years, from 315 ppm to 407 ppm today. CO2 concentrations tend to ebb and flow with the seasons, dipping as vegetation grows in the summer and increasing during the winter. The burning of fossil fuels has contributed to a steady increase in annual measurements. But in the study published in Nature, scientists at the U.K.’s Met Office and the University of California, San Diego warned that because of the recent El Nino, CO2 concentrations wouldn’t fall below 400 ppm this year, or any year into the distant future. “Once you have passed that barrier, it takes a long time for CO2 to be removed from the atmosphere by natural processes,” climate scientist and lead author of the study Richard Betts told The Guardian. “Even if we cut emissions, we wouldn’t see concentrations coming down for a long time, so we have said goodbye to measurements below 400 ppm.” The study is based on measurements taken at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. Scientists first began tracking daily CO2 levels at the site, which sits atop a volcano, in 1958. The resulting record, known as the Keeling Curve, is one considered a pillar of modern climate science. This article was first published in Yale Environment 360 |

Read |

| July 4, 2016 |

Equality And Sustainability: Can We Have Both?

by Diego Mantilla, Countercurrents.org  Recently, in this blog, Jacopo Simonetta raised a very important question: Would a fairer distribution of income worldwide diminish the damage humans are doing to the earth? His answer, that it would not and would actually make matters much worse, intrigued me. So, I decided to look at the best available data. Simonetta specifically looked at the question of whether a fairer distribution of income would reduce global CO2 emissions. In 2015, Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty (henceforth C-P) wrote a paper and posted online a related dataset that dealt with the global distribution of household consumption and CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent = CO2 and other greenhouse gases) emissions in 2013. The data are not perfect, but they are the best that exist. The C-P dataset captures the Household Final Consumption Expenditures (HFCE) values provided by the World Bank, using the distribution of income in Branko Milanovic’s dataset (for the bottom 99 percent) and in the World Wealth and Income Database (for the top 1 percent). (Income is not the same as consumption, and C-P assume that the distribution of income is the same as that of consumption. Also, they assume that the same distribution of income that existed in 2008 also existed in 2013. Like I said, the dataset is not perfect). The C-P dataset includes 94 countries, which cover 87.2 percent of the earth’s population, about 6.2 billion people, who are responsible for 88.1 percent of global CO2e emissions. Generally speaking, C-P divide each country in “11 synthetic individual observations (one for each of the bottom nine deciles, one for fractile P90-99, and one for the top 1%).” The following chart shows consumption per capita and CO2e emissions per capita in 2013 from the C-P dataset. .png)

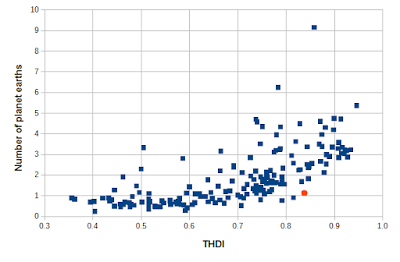

Figure 1. Consumption and CO2e emissions per capita by world consumption percentile in 2013. (Some percentiles are missing due to the fact that the country quantiles vary in size and sometimes extend beyond a given global percentile.) (Source: own elaboration from data of Chancel and Piketty (2015).) The top 1 percent on the consumption scale spend an average $135,000 (2014 PPP dollars) and emit an average 72 tCO2e per person per year. The threshold for belonging to the top percentile is $54,000. Their consumption is equal to 18 percent of all the money spent by households around the world. Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that consumption equals income. If one were to take all the income of the top 1 percent and distribute it among the 99 percent, each person in the 99 percent would get about $1,400. C-P assume a CO2e emissions to consumption spending elasticity of 0.9. A 10 percent increase in consumption means a 9 percent increase in CO2e emissions. This is a broad generalization, and C-P have a range of elasticities, but they chose that one because it is the median value of the estimates. Using that elasticity in the C-P dataset, if each person in the bottom 99 percent got $1,400 and those in the top 1 percent were left with nothing, global CO2e emissions would increase by 9 percent. But, of course, the top 1 percent are only part of the problem. About 22 percent of the world’s population lives with a consumption level above the global mean of about $8,000 per year. Let’s assume that everyone had a level of consumption equal to the mean. Going back to the C-P dataset, if one averages the CO2e emissions of everyone within a consumption bracket ranging from $7,700 to 8,300, one gets an average emission of 6.15 tCO2e per person per year. If everyone had that kind of emission, global CO2e emissions would be practically the same they are today, but, needless to say, that would improve the lot of more than three-quarters of the world’s population. In short, a perfect distribution of income would have a negligible effect on global CO2e emissions. There remains the question: At what level of consumption would CO2e emissions be reduced dramatically and would this level be compatible with a decent existence? Cuba offers an interesting example. Moran et al. (2008) looked at the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI) and the Ecological Footprint of 93 countries for 2003, and worked on the assumption “that an HDI of no less than 0.8 and a per capita Ecological Footprint less than the globally available biocapacity per person [one planet earth] represent minimum requirements for sustainable development that is globally replicable.” Their survey showed that only one country met both of those requirements, Cuba. Cuba also has the second lowest fertility rate of the Americas, 1.61 births per woman. Only Canada’s is lower. This means that a low-consumption society can be compatible with no population growth. The average Cuban eats 3,277 calories a day. Cubans have a life expectancy at birth of 79.4 years. This is above the United States and only 1.5 years below Germany. And Cuba’s mean years of schooling are above Finland’s. And only Monaco and Qatar have more doctors per capita than Cuba. Clearly, a level of consumption compatible with the finite planet that we have does not have to equal penury and destitution for everyone. I’m not saying life in Cuba is easy for everyone. It isn’t, but at some point in the near future, those who live in the developed world and in the rich enclaves of the developing world are going to be faced with a choice between a Cuban lifestyle and, to quote Noam Chomsky, the destruction of “the prospects for decent existence, and much of life.” I wanted to find out if the findings of Moran and colleagues were still true today, but I made one change. The HDI is built using three dimensions: life expectancy, education, and per capita income. This has always bothered me. A long, healthy life and an educated population are no doubt hallmarks of human development. But, is driving a Lexus a sign of human development? I think not. Therefore, I used the UN’s data to build an index that looks only at life expectancy and education, which I’m calling the truncated human development index (THDI). (The calculation of the HDI is explained here. The THDI follows the same procedure used from 2010 onward, but it only takes the geometric mean of the first two variables.) In the following chart, I plot the THDI versus the Ecological Footprint, measured in the number of planet earths the inhabitants of a given country consume, using the most recent data.

Figure 2. THDI and Ecological Footprint of 176 countries. The red dot represents Cuba. (The THDI corresponds to 2014, the Ecological Footprint to 2012.) (Source: own elaboration from data of the UN and Global Footprint Network.) There are only two countries in the vicinity of one earth that have an THDI higher than 0.8, Georgia and Cuba, the red dot. Of the two, Cuba has the highest THDI. It’s interesting that Cuba has practically the same THDI as Chile, but Chile uses 2.5 earths. And it has practically the same THDI as Lithuania, but Lithuania uses 3.4 earths. Furthermore, Cuba uses as many earths as Papua New Guinea, but Papua New Guineans have an average of 4 years of schooling, Cubans 11.5. This is just to show the possibilities that exist for an egalitarian, sustainable society. As of late, inequality in Cuba has been on the rise. However, according to the World Bank, CO2e emissions per capita in Cuba are not substantially different today than they were in 1986, when Cuba’s Gini coefficient was very low, 0.22 (Mesa-Lago 2005, page 184). In any case, I’m not advocating that we copy the Cuban model completely. I’m not defending Cuba’s crackdown on individual liberties, freedom of speech among them. All I’m saying is Cuba is an interesting example of the possibilities that an egalitarian society offers. I, for one, would like to live in a society that is even more egalitarian than Cuba. It seems to me that there is no reason in principle why humans cannot build a society that is more egalitarian than Cuba and just as sustainable, especially when the alternatives are dire. Cuba is not in the C-P dataset. It is hard to estimate the level of consumption of Cubans in dollars, because the statistics the Cuban government publishes are not comparable with those of the rest of the world, but last year the UN published a GNI per capita number for Cuba for 2014 that seems to be solid and comparable to other countries, 2011 PPP $7,301. That number is not directly comparable to the C-P data, because C-P looked at household consumption. Assuming that the share of GNI for household consumption published by Cuba’s National Statistics Office is correct, one can estimate household consumption per capita in Cuba to be at around 2011 PPP $3,900. It’s hard to translate that to 2014 dollars, because I don’t trust the PPP conversion factor published by the World Bank, but let’s assume that the consumption of the average Cuban is around 2014 PPP $4,000. Going back to the C-P data, one can find that the average CO2e emission for a consumption bracket ranging from $3,700 to $4,300 is 3.14 tCO2e per person per year. If everyone in the world had that level of emissions, global CO2e emissions would be cut by half. And in a social system similar, but not identical, to Cuba’s, no one would starve or be unschooled, and the lot of 61 percent of the world’s population would improve. To recap, an equal level of consumption for everyone around the world at the level of today’s Cuba offers the possibility of substantially lowering human impact on the biosphere while at the same time maintaining a rather decent standard of living for all. According to the Global Carbon Project, in 2014, “the ocean and land carbon sinks respectively removed 27% and 37% of total CO2 (fossil fuel and land use change), leaving 36% of emissions in the atmosphere.” If CO2 emissions were cut by half, all of them would be removed by the earth’s sinks, and there would be no net addition of CO2 to the atmosphere. It is worth pointing out that global mean consumption will reach the level of today’s Cuba eventually. The question is will that happen before humans increase the global temperature to dangerous levels. Cubans today consume 6 barrels of oil equivalent per person per year of fossil fuels, which is what Laherrère (2015, page 20) forecasts humans will consume around 2075, after the peaks of oil, natural gas, and coal production. But, by that time, according to Laherrère’s forecast (2015, page 22), humans would have emitted about 2,000 GtCO2 since 2015, 800 GtCO2 more than the maximum Rogelj at al. (2016)estimate we can emit to have a good chance of avoiding the 2 °C threshold. (Laherrère is skeptical about anthropogenic climate change, but I’m not endorsing his conclusions, just looking at his data. Diego Mantilla is an independent researcher interested in the collapse of complex societies and social inequality. He has a bachelor’s degree in computer networking from Strayer University and a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Maryland. He currently lives in Guayaquil, Ecuador. This article was first published by Cassandra’s Legacy |

Read |

| July 11, 2016 |

What Is NATO — Really?

by Eric Zuesse, World, Countercurrents.org  When NATO was founded, that was done in the broader context of the U.S. Marshall Plan, and the entire U.S. operation to unify the developed Atlantic countries of North America and Europe, for a coming Cold War allegedly against communism, but actually against Russia — the core country not only in the U.S.S.R. but also in Eastern Europe (the areas that Stalin’s forces had captured from Hitler’s forces). NATO was founded with the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington DC on 4 April 1949, and its famous core is: Article 5: The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognised by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area. However, widely ignored is that the Treaty’s preamble states: The Parties to this Treaty reaffirm their faith in the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all governments. They are determined to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilisation of their peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law. They seek to promote stability and well-being in the North Atlantic area. They are resolved to unite their efforts for collective defence and for the preservation of peace and security. They therefore agree to this North Atlantic Treaty. Consequently, anything that would clearly be in violation of “the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all governments,” or of “the rule of law,” would clearly be in violation of the Treaty, no matter what anyone might assert to the contrary. (As regards “the principles of democracy,” that’s a practical matter which might be able to be determined, in a particular case, by means of polling the public in order to establish what the public in a given country actually wants; and, as regards “individual liberty,” that is often the liberty of one faction against, and diminishing, the liberty of some other faction(s), and so is devoid of real meaning and is propagandistic, not actually substantive. Even the “rule of law” is subject to debate, but at least that debate can be held publicly within the United Nations, and so isn’t nearly as amorphous. Furthermore, as far as “individual liberty” is concerned, the Soviet Union was a founding member of the UN and of its Security Council with the veto-right which that entails, but was never based upon “individual liberty”; and, so, whatever “rule of law” the UN has ever represented, isn’t and wasn’t including “individual liberty”; therefore, by the preamble’s having subjected the entire document of the NATO Treaty to “the principles and purposes of the Charter of the United Nations,” the phrase “individual liberty” in the NATO Treaty isn’t merely propagandistic — it’s actually vacuous.) The NATO Treaty, therefore, is, from its inception, a Treaty against Russia. It is not really — and never was — a treaty against communism. The alliance’s ideological excuse doesn’t hold, and never was anything more than propaganda for a military alliance of America and its allies, against Russia and its allies. Consequently, the Warsaw Pact had to be created, on 14 May 1955, as an authentic defensive measure by Russia and its allies. This had really nothing to do with ideology. Ideology was and is only an excuse for war — in that case, for the Cold War. For example, a stunningly honest documentary managed to be broadcast in 1992 by the BBC, and showed that the U.S. OSS-CIA had begun America’s war against “communism” even at the very moments while WW II was ending in 1945, by recruiting in Europe ‘former’ supporters of Hitler and Mussolini, who organized “false flag” (designed-to-be-blamed-against-the-enemy) terrorist attacks in their countries, which very successfully terrified Europeans against ‘communism’ (i.e., against Russia and its allies). As one of the testifiers in that video noted (at 6:45), “In 1945 the Second World War ended and the Third World War started.” The ‘former’ fascists took up the cause against “communism” but actually against Russia; it wasn’t democracy-versus-communism; it was fascists continuing — but now under the ‘democratic’ banner — their war against Russia. This operation was, until as late as 1990, entirely unknown to almost all democratically elected government officials. The key mastermind behind it, the brilliant double-agent Allen Dulles, managed to become officially appointed, by U.S. President Eisenhower in 1953, to lead the CIA. Originally, that subversive-against-democracy element within the CIA had been only a minority faction. Dulles had no qualms even about infiltrating outright Nazis into his operation, and his operation gradually took over not only the U.S. but its allies. His key point man on that anti-democracy operation was James Angleton — a rabid hater of Russians, who was as psychopathic an agent for America’s aristocracy as was Dulles himself. But the CIA was only one of the broader operation’s many tentacles, others soon were formed such as the Bilderberg group. Then, the CIA financed the start of the European Union, which was backed strongly by the Bilderbergers. This was sold as democratic globalism, but it’s actually fascist globalism, which is dictatorial in a much more intelligent way than Hitler and Mussolini had tried to impose merely by armed force. It relies much more on the force of deception — force against the mind, instead of against the body. Mikhail Gorbachev failed to recognize this fact about NATO (its actual non-ideological, pure conquest, orientation) in 1990, when he agreed and committed to the dismemberment and end of Russia’s established system of alliances, without there being any simultaneous mirror-image termination of America’s system of alliances — including NATO. He wasn’t at all a strategic thinker, but instead tried to respond in a decent way to the short-term demands upon him — such as for immediate democracy. He was a deeply good man, and courageous too, but unfortunately less intelligent than was his actual opponent at that key moment, in 1990, George Herbert Walker Bush, who was as psychopathic as Gorbachev was principled.

Investigative historian Eric Zuesse is the author, most recently, of Originally posted at |

Read |

| July 12, 2016 |

Undoing The Ideology Of Growth

by Matthias Schmelzer, Counter Solutions, Countercurrents.org  Degrowth aims at undoing growth. Undoing growth both at the level of social structures and social imaginaries. Although the focus is very often on the latter, i.e. the “decolonization of imaginaries” as put by Serge Latouche, the degrowth perspective still seems to lack a comprehensive understanding of the role of ideology, the path dependencies and the power that shape these imaginations. Degrowth and related transition ideas sometimes appear as a rather naïvely idealistic perspectives, in which “we” simply have to understand, reflect and overcome our “mental infrastructures” and our personal addictions to consumerism and material expansion. This, the powerful narrative goes, will enable us to change our ways of seeing the world, to change our personal behaviour, and thus to overcome societies´ dependence on fossil capitalism and economic expansion. My recently published book The Hegemony of Growth. The OECD and the Making of the Growth Paradigm is an attempt to give more historical and social depth to our understanding of what the undoing of growth would actually entail. Without falling in the opposite trap of entirely disregarding the role of knowledge and collective imaginaries in favor of economic and social structures, I propose to understand the growth paradigm as a historically constructed and powerfully hegemonic ideology. What do I mean by this and what are the key arguments of the book? Economic growth has become and largely remains what scholars from various fields, including renowned historians, have described as a “fetish” (John R. McNeill) or “obsession” (Barry Eichengreen, Elmar Altvater), an “ideology” (Alan Milward, Charles S. Maier), a “social imaginary” (Cornelius Castoriadis, Serge Latouche), or an “axiomatic necessity” (Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen). However, while growth is at the center of both public and academic debates, the question of how economic growth actually attained its status as an overarching priority in the first place has not received much attention by historians, nor by researchers in other disciplines. Even more striking is the absence of any historical perspective in the various current efforts to overcome the focus on growth. Both the search for new statistical measures “Beyond GDP” and the lively debates about political alternatives to the growth fetish – postgrowth or degrowth – are fundamentally a-historical in that they largely ignore and underestimate the long-term historical roots, path dependencies, and power relations of statistical standards and the growth paradigm more generally. Why focus on history and the OECD?I took up this challenge by asking the simple question: How did economic growth come to be almost universally seen as a self-evident goal of economic policy-making and how was this constantly reproduced in changing circumstances? In order to answer this question in a transnational context and grounded in historical and institutional developments, I focused on the emergence and evolution of knowledge about economic growth within the OECD and its predecessor, the Organization for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), one of the least researched international organizations. I researched the archives of this organization and of some of its key member countries, read texts by key protagonists on growth theory, growth debates and the critique of economic growth, and discussed my arguments with colleagues and fellow activists. Digging deep into history and analyzing growth-thinking at the transnational level and the interface of academia, national bureaucracies, and international organizations reveals the complex and contested history and politics behind the emergence, functioning, and evolution of what I describe as the “economic growth paradigm.” The resulting book is both profoundly historical – retelling in detail the making and remaking of the growth paradigm in the second half of the twentieth century – and topical for current discussions around inequality, climate change and the end of growth. It argues that the pursuit of economic growth is not a self-evident goal of industrialized countries’ policies, but rather the result of a very specific ensemble of discourses, economic theory, and statistical standards that came to dominate policy-making in industrialized countries under certain social and historical conditions in the second half of the twentieth century. Thus, I aim at analyzing the idea of economic growth in its historical genesis in a similar way as this has been done with regard to the idea of “development” by cultural anthropologists of the so-calledPost-Development school, focusing on the close nexus of power and knowledge. It rests on the thesis that the exceptional position of economic growth as a core policy goal is based on the hegemony of the growth paradigm and cannot be adequately understood without taking into account the complex structure and historical evolution of this paradigm. The growth paradigm in the history of capitalismThe making of this core feature of the religion of capitalism has to be situated within longer-term developments that reach back to the onset of intensified capitalist industrialization in the early eighteenth century or even further, to colonial expansions. At that time, a secularized conception of economic progress and a first generation of classical growth theories emerged which, however, fell into oblivion with the rise of econometrics and neoclassical economics in the later nineteenth century. Building on statistical developments in the early twentieth century, it was only in the context of the Great Depression that a renewed interest in macroeconomic questions gave rise to the modern conception of “the economy” and to interventionist economic policies geared toward stability and employment. Yet it was not before the late 1940s and early 1950s that in the context of World War II, European reconstruction and Cold War competition, economic expansion became a key policy goal throughout the world. The growth paradigm emerged as part of what has been called “high modernism,” a system of beliefs and practices aimed at increasing the power of the state in line with what was believed to be scientific ideas in order to reshape societies by maximizing production to improve the human lot. Four unquestioned allegations were specifically relevant in reinforcing the hegemony of growth and collectively rationalized, universalized, and naturalized the growth paradigm. These assumed that GDP, with all its inscribed reductions, assumptions, and exclusions, adequately measures economic activity; that growth is a panacea for a multitude of (often changing) socioeconomic challenges; that growth is essentially unlimited, provided the correct governmental and inter-governmental policies were pursued; and that GDP-growth is practically the same as or a necessary means to achieve essential societal goals such as progress, well-being, or national power. Growth as ideology – an “imaginary resolution of real contradictions”The growth paradigm became hegemonic in the sense of justifying and sustaining a particular perspective – the allegations mentioned above – and the underlying social and power relations as natural, inevitable, and timeless. Growth came to be presented as the common good, thus justifying the particular interests of those who benefited most from the expansion of market transactions as beneficial for all. The hegemony of growth depoliticized key societal debates about what societies value, how they interpret their current position historically and within the globalized economy, and how they conceptualize the good life and future developments. Growth turned difficult political conflicts over distribution and the goals of policy-making into technical, non-political management questions of how to collectively increase the economic output of the nation state. By transforming class and other social antagonisms into apparent win-win situations, it provided what could be called an “imaginary resolution of real contradictions” (Terry Eeagleton). Economic growth and the superiority of economistsMoreover, by transforming contested and changing societal goals into technical economic problems, growth discourses have deeply colonized our imaginaries: they not only reinforced the dominance of economic thinking and arguments by turning political or social questions into economic problems (what could be called “economism”), but they also strengthened the privileged positions of economic technocrats within modern societies and underpinned the primacy of the economy over politics. Growthmanship was mutually reinforced along with the increasing importance of economic knowledge production as a key justificatory basis for policy-making within the modern state. The economists’ ability to measure, model, and steer growth made them increasingly indispensable for managing modern societies based on growth and thus reinforced the “superiority of economists” just as the expansion of economic approaches also strengthened the growth paradigm. Even though the mid-twentieth century saw the proliferation of growing armies of experts, ranging from international relations theorists to demographers, anthropologists, sociologists to agronomists, economists were the only ones who managed to claim the mastery over what had become a fetish throughout the world: economic growth. These arguments – and others – are weaved into the various case studies discussed in the chapters of the book. These focus on issues such as the international standardization of national income accounting, the transnational harmonization of growth policies, the development of growth into a universal yardstick, the replication of growth policies in the context of decolonization and the ‘development of others,’ the OECD-Club of Rome nexus, the birth of environmental politics and social indicators, as well as the more recent turn to neoliberal growthmanship. To conclude, overcoming the ideology of growth – or what’s recently been called the “growthocene” – demands a thorough understanding of what we are up against. The degrowth movement set out to dismantle a paradigm that has deep historical roots and is embedded in and thus supported by powerful institutions and structures such as the nation state, capitalism, established understandings of “the economy”, or the power of economists in societies. Most importantly, however, growth has arguably become one of the key justificatory ideologies of capitalism. Not only large scale inequalities – as recently publicized by Thomas Piketty – and the divergence of uneven development between rich and poor nations are justified as of a temporary nature, to be overcome by more growth in the future, but similarly societal cleavages along the lines of class, race and gender. With climate change, resource limits, and secular stagnation, this make-believe “resolution of real contradictions” reveals itself as clearly “imaginary.” Consequently, in order to dismantle the hegemony of growth, degrowth has to develop a profound and critical understanding of the real societal contradictions, hierarchies and power dynamics shaping capitalism and transform them in new ways. |

Read |

| June 17, 2016 |

'We’re Officially Living in a New World': Antarctica Hits Highest CO2 Level in 4 Million Years

by Brian Kahn, Climate Central, AlterNet  We’re officially living in a new world. Carbon dioxide has been steadily rising since the start of the Industrial Revolution, setting a new high year after year. There’s a notable new entry to the record books. The last station on Earth without a 400 parts per million (ppm) reading has reached it. A little 400 ppm history. Three years ago, the world’s gold standard carbon dioxide observatory passed the symbolic threshold of 400 ppm. Other observing stations have steadily reached that threshold as carbon dioxide spreads across the planet’s atmosphere at various points since then. Collectively, the world passed the threshold for a month last year. In the remote reaches of Antarctica, the South Pole Observatory carbon dioxide observing station cleared 400 ppm on May 23, according to an announcement from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on Wednesday. That’s the first time it’s passed that level in 4 million years (no, that’s not a typo). There’s a lag in how carbon dioxide moves around the atmosphere. Most carbon pollution originates in the northern hemisphere because that’s where most of the world’s population lives. That’s in part why carbon dioxide in the atmosphere hit the 400 ppm milestone earlier in the northern reaches of the world. But the most remote continent on earth has caught up with its more populated counterparts. “The increase of carbon dioxide is everywhere, even as far away as you can get from civilization,” Pieter Tans, a carbon-monitoring scientist at the Environmental Science Research Laboratory, said. “If you emit carbon dioxide in New York, some fraction of it will be in the South Pole next year.” It’s possible the South Pole Observatory could see readings dip below 400 ppm, but new research published earlier this week shows that the planet as a whole has likely crossed the 400 ppm threshold permanently (at least in our lifetimes). Passing the 400 ppm milestone in is a symbolic but nonetheless important reminder that human activities continue to reshape our planet in profound ways. We’ve seen sea levels rise about a foot in the past 120 years and temperatures go up about 1.8°F (1°C) globally. Arctic sea ice has dwindled 13.4 percent per decade since the 1970s, extreme heat has become more common and oceans are headed for their most acidic levels in millions of years. Recently heat has cooked corals and global warming has contributed in various ways to extreme events around the world. The Paris Agreement is a good starting point to slow carbon dioxide emissions, but the world will have to have a full about face to avoid some of the worst impacts of climate change. Even slowing down emissions still means we’re dumping record-high amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year. That’s why monitoring carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa, the South Pole and other locations around the world continues to be an important activity. It can gauge how successful the efforts under the Paris Agreement (and other agreements) have been and if the world is meeting its goals. “Just because we have an agreement doesn’t mean the problem (of climate change) is solved,” Tans said. Brian Kahn is a Senior Science Writer at Climate Central. He previously worked at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society and partnered with climate.gov to produce multimedia stories, manage social media campaigns and develop version 2.0 of climate.gov. His writing has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Grist, the Daily Kos, Justmeans and the Yale Forum on Climate Change in the Media. |

Read |

| June 24, 2016 |

How Fracking for Natural Gas Became the Terrible New Norm

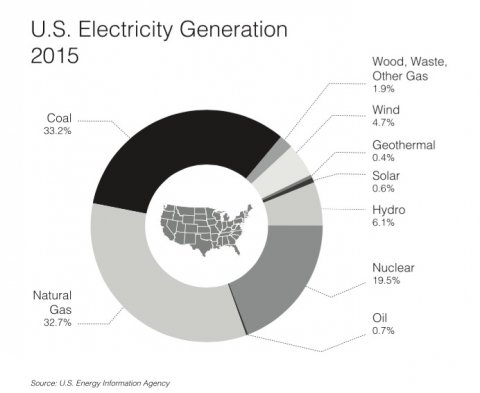

by Wenonah Hauter, The New Press, AlterNet  The following is an excerpt from the new book Frackopoly by Wenonah Hauter (The New Press, 2016): Over my decades of work in the public interest, I have developed a thick skin. If we are doing our job in the environmental movement, it is par for the course to be sneered at and called names. So when I heard that I had been pegged as “too strident” by the president of one of the largest energy and environment funders in the country, I was hardly surprised, as it has long been an institution that funds groups promoting policies to incentivize natural gas. In fact, I was pleased. I thought: Yes, it’s time to become much more forceful in protecting our threatened planet. It’s time for everyone to be strident about keeping fossil fuels in the ground and eliminating the dirty energy technologies of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, even as hundreds of grassroots groups are battling to stop fracking, some of the largest environmental groups in the nation and many of their funders tout fracked natural gas as a “bridge fuel” or at least tacitly accept its use. Rather than focusing on an all-out effort to move away from fossil fuels, some of these groups provide cover to the fracking industry, claiming that fracking can be done safely or ignoring fracking’s implications for the global climate.

Meanwhile, the communities that are living with the effects of the technology, or the ones fighting the coming wave of fracking and the associated infrastructure, feel betrayed when the place where they live becomes a sacrificial zone—with the implicit approval of some environmental organizations. A closer look at the path that these groups have laid out reveals that it will take us down the road to an environmental and climate disaster. Instead, we should aggressively deploy technologies for clean and renewable resources, reorient the energy system around conservation and efficiency, and leave fossil fuels in the ground, where they belong. In many ways, fracking looms as the environmental issue of our times. It touches every aspect of our lives—the water we drink, the air we breathe, and the health of our communities—and it ominously threatens our global climate. It pits the largest corporate interests—big energy and Wall Street—against people and the environment in a long-term struggle for survival. Understanding the impacts of fracking and the policy decisions that have led to this dangerous point in time are key to moving beyond extreme energy. Recent climate science shows that switching to natural gas is unlikely to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for decades, a crucial time frame for stopping runaway climate disruption. When the entire life cycle of producing natural gas is examined, the damage from methane leakage puts it on par with coal, or worse. The most conservative estimate from atmospheric measurements—not from the inventorying based on oil and gas company data—is that natural gas leakage in 2010, averaged over the country, amounted to more than 3 percent of U.S. production that year. Even if methane leakage can be brought down significantly over time—a debatable scenario—the threat to the global climate in the short term is very real. The rapid transition to natural gas is sending us to a tipping point when climate change cannot be reversed. Despite the overwhelming evidence of the harms of fracking, the Environmental Protection Agency has thus far ignored the science. Obama’s energy secretary Ernest Moniz has close ties with the industry and has claimed that he has “not seen any evidence of fracking per se contaminating groundwater” and that the environmental footprint is “manageable.” Obama’s interior secretary Sally Jewell has bragged about fracking wells in her prior career in the industry and has, despite radical changes in how fracking is done, called it a “an important tool in the toolbox for oil and gas for over fifty years” and even implied that directional drilling and fracking can result in “a softer footprint on the land.” And the person charged with protecting communities’ water, EPA administrator Gina McCarthy, has claimed that “there’s nothing inherently dangerous in fracking that sound engineering practices can’t accomplish,” all while the EPA has ignored or buried findings that fracking has contaminated water in Texas, Wyoming, and Pennsylvania. If we are to tackle the enormous threat posed by fracking and the fossil fuel industry, it is crucial to understand how the policy decisions of the last forty years have led us away from sustainable energy and toward a reliance on natural gas. The devil truly is in the details. While many well-meaning environmentalists believe that we are making real progress on renewable energy, the data on the percentage of electricity generated by nonrenewable energy sources tells a different story. Although the emphasis on individual action—putting solar on rooftops—is a step in the right direction, serious policy changes must be made to displace the large amount of energy produced by natural gas, coal, and dangerous nuclear power. Solar power generated only 0.2 percent of the nation’s electricity on average between 2010 and 2014, and wind energy supplied 3.6 percent. If geothermal energy is added to the equation, the renewable share grows to 4.2 percent. Hydropower generates 7 percent of the nation’s electricity, but this amount may decrease over time because of the impacts on river ecosystems. Over the past five years, fossil fuels continued to power two-thirds of America’s electric sockets. Coal power generated almost 42 percent of electricity, and natural gas generated nearly 26 percent. Some green groups claimed if electricity was deregulated, renewables would thrive and nuclear plants would be retired, but a close examination of the numbers shows that this has never happened. Nuclear power has hovered at around 20 percent of electricity production since the 1990s and is expected to increase little if at all. Old plants will be taken out of production over the next twenty years, although if nuclear power is allowed to benefit from cap-and-trade policies, new plants may be built, subsidized by taxpayer money. Coal electricity has declined from 53 percent of generation between 1995 and 1999 to almost 42 percent over the most recent five years. It will continue to decline as a result of the adoption of the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan—a set of policies designed to replace coal-generated electricity with natural gas. Lower natural gas prices and federal mandates to reduce mercury and carbon dioxide are shifting electricity production toward natural gas and away from coal-fired generation. Natural gas has been the big winner, with generation increasing every five years since natural gas was deregulated in the 1980s. Natural gas generation has doubled from about 13 percent in the late 1990s to nearly 26 percent in recent years. Natural gas production increased an average of 5 percent a year beginning in 2000. According to a 2014 report by the EIA (Energy Information Administration), between 2012 and 2040, 42 percent of the total increase in electricity generation will be from natural gas. Coal-fired generation’s share of total generation will decline to 34 percent in 2040, while natural gas will rise to 31 percent. But the predictions for renewables are shockingly low, with EIA predicting that solar will still make up 1 percent of electricity generation and wind 7 percent in 2040. Predictions about energy use are often proven wrong, and the complexity of energy use and production means that changes in policy frequently have many unplanned consequences. But one thing is certain: over the past forty years, the schemes favoring the use of natural gas, and to provide cheap energy to the largest industrial users of natural gas and electricity have proven successful, with dire consequences for the environment, consumers, and our democracy. The Koch brothers have been major funders of the scheme that has landed us where we are today. Ideologically opposed to any regulation, they also have sought policy changes that would benefit their bottom line— seeking changes in natural gas and electricity policies that would facilitate cutting special deals for cheaper energy, while shifting costs to residential and small-business consumers. David Koch founded the Cato Institute in 1974, one of the think tanks pushing deregulatory policies and working with other right-wing actors such as the Heritage Foundation. Mindful of the tactics used by public interest groups, Charles and David Koch eventually decided to pursue a similar strategy by founding Citizens for a Sound Economy (CSE) in 1984, leading a grassroots-style campaign to oppose regulation and taxes. David Koch explained of their thinking:

The fossil fuel industry had been attempting to deregulate the natural gas industry since the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. After three decades of bitter legislative, regulatory, and legal battles, progressive forces lost the long fight over the pricing of natural gas and oversight of pipelines, beginning with the passage of the Natural Gas Act of 1978. By 1990, after a series of deregulatory policy changes, a highly speculative wholesale market in natural gas developed, with Wall Street gambling determining the price that consumers paid for natural gas and incentivizing future natural gas development. The New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), a commodity futures exchange, applied to the U.S. Commodities Future Trading Commission to trade natural gas futures on February 29, 1984, and trading commenced on April 4, 1990. Between 1985 and 1990, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) had also made deregulatory changes to the rules for moving natural gas from wellheads to end users. Pipeline companies were required to separate gas sales, transportation, and storage services, giving large industrial customers an advantage and creating an incentive to build more pipelines. The deregulatory policies spurred a frenzy of pipeline construction that has continued unabated through the fracking boom, creating widespread habitat damage and posing safety risks. Between 1984 and 2014, gas companies added at least 936,000 miles of pipeline—about 85 miles every day—and there are now 2.5 million miles of transmission, distribution, and gathering lines. Further, thousands of miles of unregulated high-pressure pipelines with much larger capacity for transferring natural gas to processing facilities— referred to as gathering lines—have proliferated since fracking, although no cumulative record of the mileage exists. The radical changes in the rules governing the natural gas industry inspired a ferocious lobbying campaign to make similar changes to the electric industry, changes that would eventually drive the use of natural gas for electricity. Breaking up the $200 billion (more than $300 billion adjusted for inflation) electric industry offered an opportunity to create a battle of titans, as they fought among themselves over the rules that would benefit their particular economic interest. Using a politically loaded vocabulary to win converts, they claimed that it would unleash competition, broaden consumer choice, and lower the cost of electricity. Spearheaded by institutions affiliated with the Koch brothers, including CSE and the Cato Institute, a politically powerful coalition emerged in the 1990s to restructure the electric industry. Large coal utilities like American Electric Power Inc., and natural-gas-power marketers—companies like discredited and bankrupt Enron—were at the forefront of the lobbying machine to transform the electric industry. Proponents of deregulation sought to separate power generation from transmission and distribution, creating an unregulated wholesale market where middlemen could speculate on buying and selling electricity. Wall Street—investment houses, rating agencies, and financial analysts—fueled the drive to make electricity another tradable commodity. The changes that they wrought created a market where power producers, retailers, and other financial intermediaries could speculate on short-and long-term contracts for electricity. After deregulation, the marketplace was supposed to be self-governing, begetting cheap and reliable electricity. The turning point began in 1992, when C. Boyden Gray, the White House counsel to President George H.W. Bush, engineered the inclusion of provisions in the Energy Policy Act of 1992 that fast-forwarded electricity deregulation. Gray, a millionaire heir to a tobacco fortune, has been closely affiliated with the Koch-funded front groups throughout his long career as a corporate lobbyist, presidential adviser, and U.S. diplomat. Concealed within the compromise legislation was language removing important limitations on the ownership of electricity generation, which had protected consumers. It also authorized FERC to issue orders that changed the structure of the electric industry over the second half of the decade, creating a casino-like atmosphere in the wholesale electricity market and driving construction of new gas-fired power plants. The FERC orders allowed states, if there was the desire, to rewrite the rules by which residential and small business purchased electricity. The natural gas industry, led by Enron, launched a massive lobbying campaign to “unleash market forces,” pushing for even more deregulation at the state level. Claiming that a new era of competition would replace bloated and inefficient utilities with lean and mean power marketers like Enron, California became the first state to succumb to the rhetoric, allegedly giving consumers a choice about their electricity provider. The large investor-owned utilities wrote the legislation, however, protecting their favored economic position. Between 1999 and 2001 a small cartel of energy companies was able to use the new layer that had been created between the producing and distributing of electricity to make billions of dollars by price-gouging consumers. Californians were overcharged by almost $25 billion during the first five years of deregulation, as power marketers manipulated electricity supply and natural gas prices, causing a series of rolling blackouts throughout the state. In the end, California and several other states that had deregulated this essential service instituted some form of regulation again. CSE, Enron, and the other advocates of state-based deregulation had pushed for federal legislation that would force states to forsake cost-based regulation, which limits energy company profiteering. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the powerful coalition promoting electricity deregulation spent $50 million between 1998 and 2000 on lobbying to change the rules under which electric utilities operate. Although the calamity in California set back industry efforts to pass federal legislation compelling states to restructure the electric industry, new efforts are afoot to push this agenda. In the meantime, the creation of the wholesale electricity market has led to a dramatic increase in natural gas–fired electricity, making the fracking industry one of the biggest beneficiaries of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's deregulatory changes. Although companies must go through a weak permitting process that varies depending on each state’s rules, no calculation of how the plan fits into a national plan for reducing pollution is made. And since the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan leaves decisions to the states, no overall examination is done on the impacts to our global climate. Advocates who warned against the unintended consequences of electricity deregulation—both for the environment and for consumers—were ignored or scorned. Foreshadowing the future support for fracked natural gas, influential foundations and public interest advocates signed on to the efforts to deregulate electricity. Without a large grassroots campaign, the green groups negotiated from a very weak position. They naively bought the argument that, by compromising, deals could be cut to expose dirty power plants to competitive forces, and that sustainable energy would be the winner. These same groups failed to oppose the elimination of a 1935 law, the Public Utility Holding Company Act (PUHCA). Restricting speculative ventures with ratepayer dollars and restraining electric utilities from operating outside of the geographic area that they served, this obscure law offered major protection to consumers and limited the already significant political power of the electric industry. It was repealed in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, at the same time that fracking was exempted from national environmental laws. This has created a handful of enormous electric utility companies that dominate political decision making about energy-related issues. The chilling predictions about PUHCA’s elimination are tragically coming true as the electric corporations consolidate at a rapid rate. Eugene Coyle, formerly an economist at the California utility watchdog group TURN, predicted in 1997, “What we are looking at is the shift from a situation where there are more than a thousand utilities nationwide, over which rate-payers have some control, to a future where there will be perhaps 10 big power companies operating free of regulation and acting like the oil cartels of old.” Reversing bad energy policy and banning fracking will take a massive grassroots mobilization that holds accountable Democrats and Republicans alike and that takes power back from the Koch brothers and their ilk. It means challenging the entrenched political establishment that grovels to the dirty energy industry and facilitates its ability to operate without suffcient oversight, transparency, or accountability. It means working shoulder to shoulder with the brave activists across the country who are challenging extreme energy rather than worrying about the opinions of mainstream funders or other institutions that have close ties to dirty energy. With mounting evidence about the harms of fracking, and the immediacy of the impending climate crisis, it is time for the major green groups to fight for a transition to real sources of renewable energy and energy efficiency, not to depend on market-based schemes with no track record of working. We can and we must build the political power to change the course of history—our survival depends on it. Copyright © 2016 by Wenonah Hauter. This excerpt originally appeared in Frackopoly: The Battle for the Future of Energy and the Environment, published by The New Press Reprinted here with permission. |

Read |

| July 6, 2016 |

Unprecedented Series of Climate Change Ads Bring Climate Reality to Wall Street Journal

by Fenton , AlterNet  An unprecedented series of 12 advertisements is underway in The Wall Street Journal, bringing accurate, mainstream climate science to readers of the Journal opinion pages. Fenton, a social change communications agency with offices in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., wrote and designed the series for The Partnership for Responsible Growth, a D.C.-based organization campaigning for a market price on carbon. The twelve ads will appear twice a week between June 14th and July 21st, ending just before the Republican Convention. They will be available at www.pricecarbon.org, a website built by Fenton. The ads cover several topics, including:

To view newly published ads as they are released online and in print on the pages of The Wall Street Journal, the supporting evidence behind each ad, and to take action in support of a market solution to climate change, visit the climate ad series website. The partnership will also buy TV ads featuring prominent Republicans on the need to address climate change, which Fenton is producing. These will appear on FOX News during the Republican Convention. |

Read |

| 2016 |

A Burst of Federal Rulemaking May Help Millions of Animals

by Wayne Pacelle, The Humane Society of the United States, AlterNet  The recent months have been big for animal protection. Walmart announced it would go cage-free for its egg purchases, and a number of other retailers did the same. “In a virtual tidal wave of announcements, nearly 100 retailers, restaurants, food manufacturers and food service companies have revealed cage-free plans in the last year,” writes Meat & Poultry magazine about The HSUS’s efforts, In April, our Humane Society International team helped to pass an anti-cruelty statute in El Salvador – this is the third country in Central America that we’ve persuaded to establish a legal standard against the practice. These are big gains in our campaign to start filling in the map of the world with anti-cruelty statutes, as we’ve done in the United States with every state. Also in April, it was a signature time for the Obama Administration in pushing animal welfare ahead through a remarkable slew of rulemaking actions and policies – a burst of activity that offers the prospect of helping all sorts of animals now at risk. Captive Tigers – Two different agencies tackled the animal welfare and conservation problems associated with the mistreatment of captive tigers.

Organic Animal Products – The USDA issued a long-awaited proposed rule toupgrade animal welfare standards for farm animals under the organic label. The rule covers a whole array of baseline standards for housing, husbandry, and management under the National Organic Program, including the prohibition of certain painful practices, like tail docking of pigs and cattle and debeaking of birds. Importantly, the rule sets minimum indoor and outdoor space requirements for egg-laying chickens, and requires that producers provide a sufficient number of exits and outdoor enrichment to entice birds to go outside on a daily basis. This proposed rule is currently open for public comment and it’s important that you weigh in with your support for increased animal welfare standards for farm animals. African Elephant Ivory – The Fish and Wildlife Service sent a final rule governing the sale of African elephant ivory to the Office of Management and Budget for White House clearance (a key step before a proposed or final rule is released to the public). FWS is seeking to curtail the commercial ivory trade in the United States with limited exceptions on interstate sales. The United States is the world’s second largest market for ivory product sales, behind China. However, there have been many efforts in Congress to derail the rule from being finalized and implemented. Please let your legislator knowhow important this rule is to protect African elephants from being slaughtered for their ivory. Horse Soring – The USDA is moving toward ending the cruel practice of “soring” by updating its regulations under the Horse Protection Act. Soring has been illegal since 1970 but it persists, which is why stronger regulatory oversight is critical and overdue. The USDA’s Office of Inspector General found in 2010 that the agency’s current program is inadequate to prevent abuse, and in February 2015, The HSUS filed a rulemaking petition with the USDA. The USDA has now sent a proposed rule to the Office of Management and Budget for White House clearance. At this stage of the review process, the text of the proposed rule is not yet public, but to be effective, it should mirror key reforms proposed by the HSUS rulemaking petition and in the Prevent All Soring Tactics (PAST) Act, including banning the stacked shoes and action devices associated with soring, and ending the industry self-policing system by replacing it with USDA trained and licensed inspectors. It’s critical that the White House quickly clear this proposed rule and open it up to public comment. These final or proposed reforms will help relieve pain, abuse, and suffering for countless animals. We are excited about every one of them, and we are thankful to leaders within the Administration and to all of the lawmakers in Congress who’ve helped push these ahead. There’s more work to be done to get all of these reforms over the finish line, in intact form, but it’s hugely promising and exciting. Wayne Pacelle is the president and CEO of the Humane Society of the United States. He is the author of the New York Times bestseller is The Humane Economy: How Innovators and Enlightened Consumers Are Transforming the Lives of Animals (William Morrow, 2016). |

Read |

| July 14, 2016 |

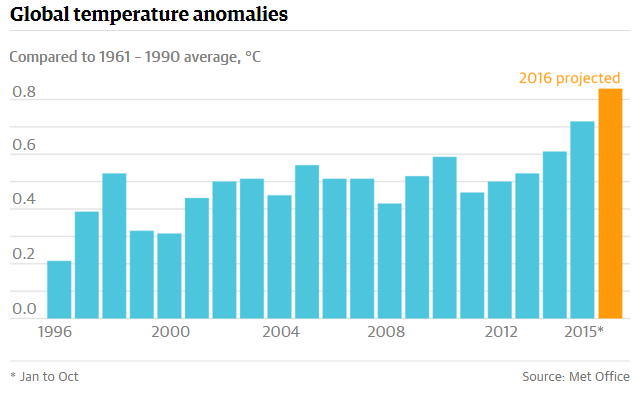

From Global Temps to Clean Energy, Broken Records Define the Climate Crisis