|

Volume 13 Issue 3 November 2014

|

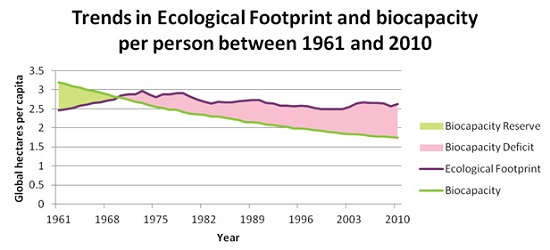

Summary image of the theme "Peace in the world with Global Community".

Building global communities require understanding of global problems this generation is facing. There are several major problems: conflicts and wars, no tolerance and compassion for one another, world overpopulation, human activities accelerating dangerously the amount of greenhouse gases in the air, as population increases the respect and value of a human life is in decline, insufficient protection and prevention for global health, scarcity of resources and drinking water, poverty, Fauna and Flora species disappearing at a fast rate, global warming and global climate change, global pollution reaching unhealthy peaks in the air, water and soils, deforestation, permanent lost of the Earth's genetic heritage, and the destruction of the global life-support systems and the eco-systems of the planet. We need to build global communities for all life on the planet. We need to build global communities that will manage themselves with the understanding of the above problems.

October 11 2014

( see enlargement 68 MB

Authors of research papers and articles on global issues for this month

Ajamu Baraka, Glen Barry, Global Footprint Network, Marie David C, Damian Carrington, Garikai Chengu, Jonathan Cook, Ronnie Cummins,

Todd Gitlin, Michael T. Klare, Sarah Lazare, Rajesh Makwana,

Larry Schwartz, Rebecca Solnit (3), David Swanson, Cliff Weathers,